The phrase “aging millennial” is sure to bum anyone out. Maybe you’re one of them, as I am, and are reading this having filed your weekly unemployment claim and waiting to hear back about that remote position you found on Twitter. Global pandemic notwithstanding, the future was always bleak.

In a 2017 Huffington Post article titled “Millennials Are Screwed,” mature millennial Michael Hobbes writes of our plight, “Salaries have stagnated and entire sectors have cratered. At the same time, the cost of a secure existence—education, housing, and health care—has inflated into the stratosphere.” The oldest millennials are turning forty at the heels of another thwarted progressive revolution. Many are abandoning notions of child-rearing or property ownership altogether. Off we go, then, aboard Citi Bikes and Toyota Camrys, to embrace this new serfdom we’ve dubbed the gig economy.

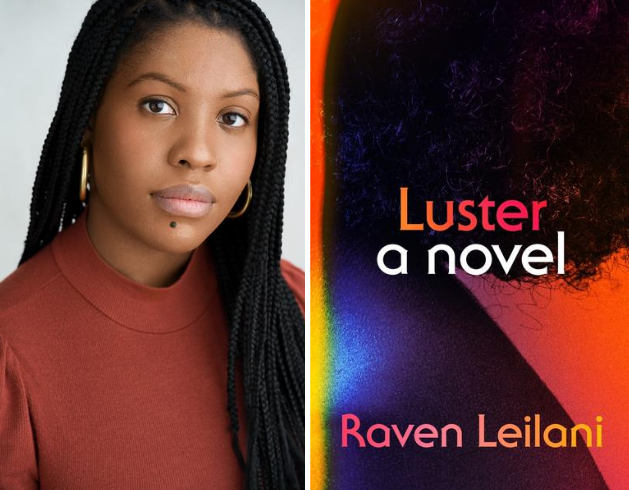

But the desire for the good life, or some semblance of it, is a stubborn flame. Raven Leilani’s sultry and sharp-witted debut novel, Luster, is brimming with the potential energy of a young person and artist battling precarity. Leilani, an aging millennial at twenty-nine, revisits the tragicomic indignities of one’s early twenties through her protagonist Edie, a painter who’s not painting much these days. Edie’s dead-end job as managing editor for a children’s imprint—a sadly poetic place for someone in arrested development—pays enough to cover student loan installments and rent in a rodent-infested Bushwick apartment.

Edie simmers with creative frustration and constantly gets her libidinal wires crossed. After her third rejection from the publishing house’s art department, she falls in bed with its director, an accomplished artist who sports a duster and “keeps fresh orchids in his office.” Leilani writes frankly about the unsavory reality that, in this country, gender parity and meritocracy seem to exist only for those already born into wealth. For the rest of us, access to the finer things is still predicated on labor exploitation—or on fucking or marrying up and the costly reputational and physical risks that come with it. “There are men who are an answer to a biological imperative, whom I chew and swallow,” Edie observes. “And there are men I hold in my mouth until they dissolve.”

Of the latter is Eric, a digital archivist in his forties whom Edie sexts while on the clock. He works uptown and claims he’s in an open marriage. Edie is drawn to older men like Eric for “having more stable finances and a different understanding of the clitoris,” and she revels “in the excruciating limbo between their disinterest and expertise.” At night, she lies awake on her futon and imagines Eric in bed with his wife somewhere in New Jersey. “It’s not that I want exactly this, to have a husband or home security system that, for the length of our marriage, never goes off. It’s that there are gray, anonymous hours like this… when I am ravenous, when I know how a star becomes a void.”