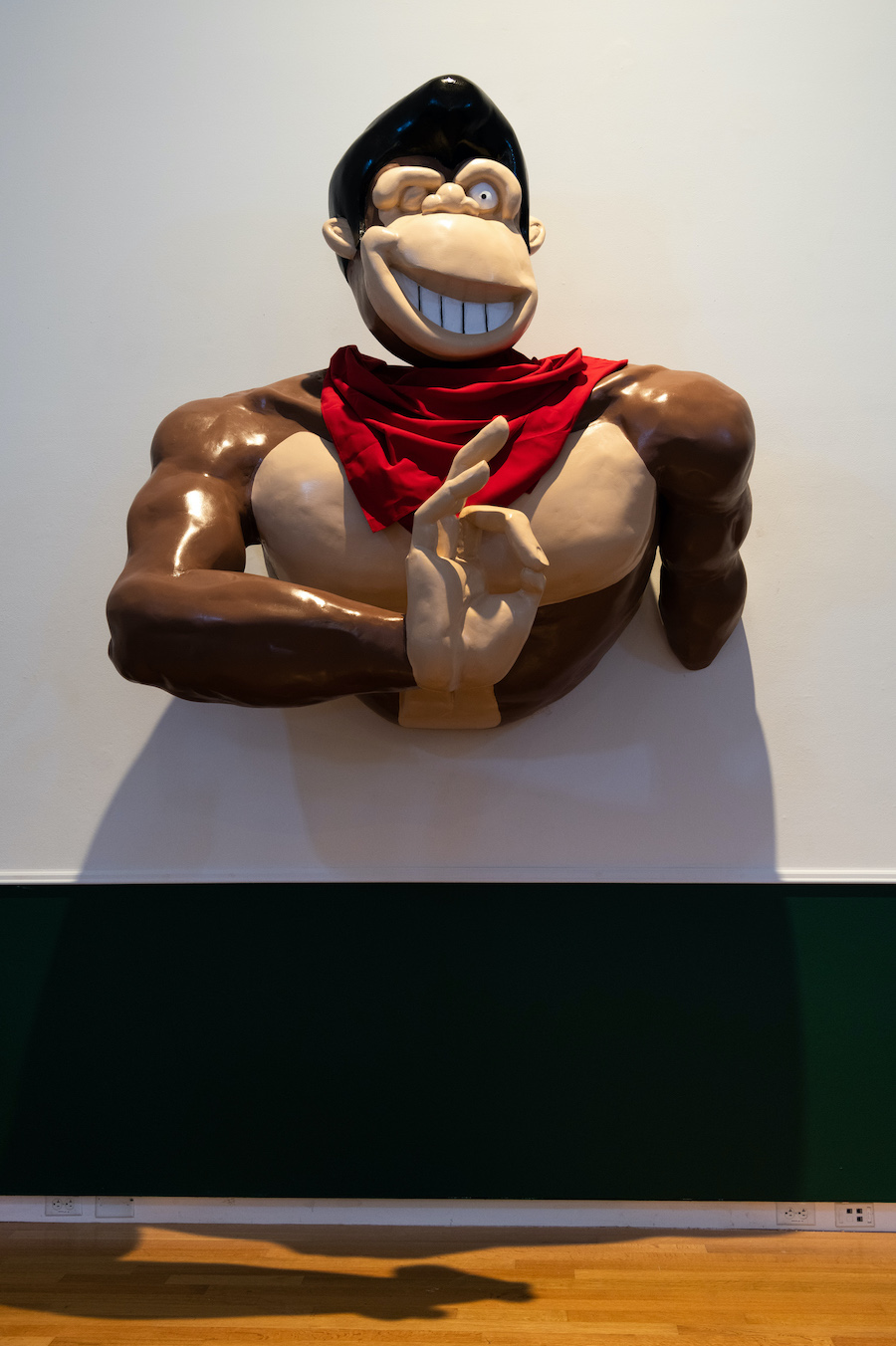

I am greeted by a frog holding aloft a serving tray. Its head is cocked a bit to the side, elbow bent and hand on the hip. Less ready to please, more this again? The image is surreal, but it’s no escapist fantasy. The figure calls to mind a lawn jockey or a blackamoor—both statues of servitude with histories steeped in racism. Welcome to Ajay Kurian’s world of Polyphemus.

Polyphemus, on view at Goucher College’s Silber Art Gallery, is an installation that takes its title from Homer’s Odyssey. In the Odyssey, Polyphemus is the name of the giant one-eyed cyclops who terrorizes—and eats—Odysseus’s men. In the Silber Gallery, Baltimore-born Kurian recreates the cyclops as an oscillating fan, mounted high on the wall, painted to echo the pupil, iris, and white of the eye. Floating by wire in front of the eye is a toothy smile made of LEDs, casting an ominous glow in the darkened space like the mischievous grin of the Cheshire Cat. Six of these cyclopes are spaced evenly throughout the room, oscillating and scanning, giving the distinct impression that we are being watched at all times, that we are operating within a surveillance state.