It is a miracle, it’s that simple. What else are you working on and how do you want your 2021 to go? If we survive *knocks on wood*—if our mental health is still intact, because I am struggling [both laugh]. So if we get there, to 2021, what would you like it to look like for you and your practice?

I just want to be able to paint and quilt again. Which I will be able to. I just finished five new quilts to exhibit at the Untitled Art Fair in Miami. I am going to have a museum exhibition in 2022 and all of that is about Black labor in the United States, so I’ll begin finishing some of the work for that show. Because I spent so much of 2020 making quilts, I’ve learned so many things, some new techniques, so I hope I’ll incorporate some of that stuff in my paintings and quilts in 2021. I’m really excited.

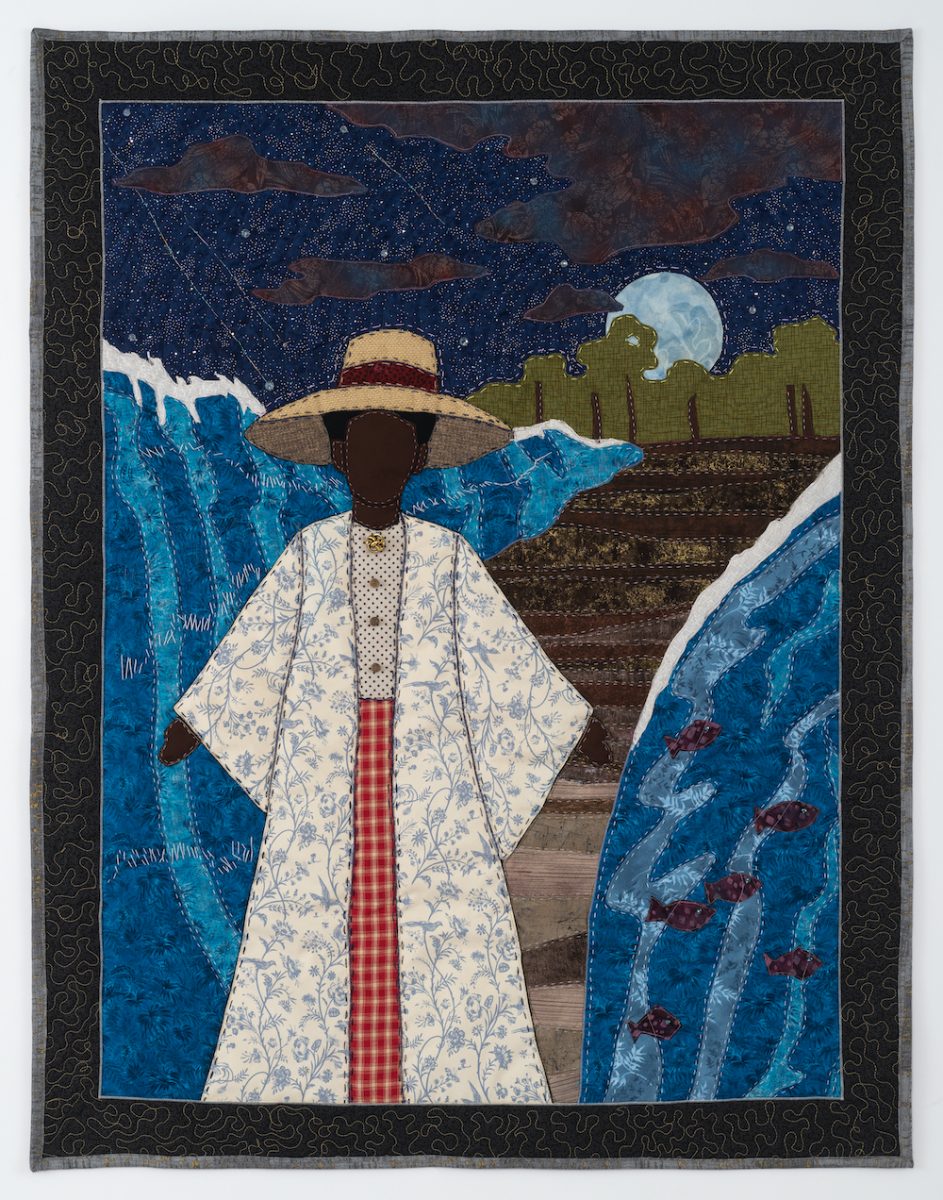

I just finished a project of quilts about Anna Murray Douglass. She was Frederick Douglass’ first wife. His first wife was Black, his second wife was white. He met Anna when he was enslaved here in Baltimore. He was working down in Fells Point at the shipyard. She was born free, and I think she was born free on the Eastern Shore, and she came to Baltimore and she was doing domestic work, but she actually worked and raised money for him to escape to New York. That’s how he went to New York and married her. She sewed his sailor’s outfit, which was the disguise that he wore to escape to New York.

So they got married, they moved around, and she had five children with him. But she spent her whole life sort of being in the background. He was as successful as he was because he had a Black woman behind him, but he was a terrible husband. He would always be hanging around white women, and he had this white woman that he would bring to their house every summer. That was probably because he was having an affair with her. Anna was not happy with her, and because Anna was taking care of the house and she took pride in taking care of it all, she would have to take care of this white woman every summer that her husband was having an affair with.

I think the thing that we don’t think of is Frederick Douglass was sort of like a basketball player in that he was very charismatic, he was good looking at the time, he had these women all over him. You have to put him in that context and put [Anna] in that context. She died and the reason that he was able to have as much money as he had and marry his second wife was that Anna helped make sure he saved the money that they each needed to save to have a successful life. She died unknown and her daughter wrote a biography about her.

The thing is, when you learn that, that does not diminish his importance. Without him, we would not be here. He is still one of the most important figures in the emancipation of Black people, despite all of that. And when you learn these things, you have to live with that. As a 20-year-old, I would not have been able to decipher that. But as an adult, it’s like, okay, he’s an imperfect person. And that’s really the hard thing: How do you allow somebody to still be a human and make a mistake?

Right, how far is grace extended? Were you able to see A Songbook Remembered in person?

Yes, we went up to NYC when they announced that Biden had won and it was such a happy weekend. They announced that and people were screaming in the streets. There were honking horns. There were people running, walking down the street, carrying flags the whole day. And the weather was just unusually warm. It was like a spring day. That whole weekend was like magic because that was the first time that everybody in a city was happy. It was like being in Oz, the house landed on the witch and everybody was happy.

[Image: Stephen Towns, Mary Had a Baby, 2020, Natural and synthetic fabric, polyester and cotton thread, crystal glass and resin beads, metal button, 47 x 36.75 inches]