“Dealing with performance art in a pandemic is nerve-racking,” admits Monsieur Zohore, a few days after organizing a guerrilla performance outside the Baltimore Museum of Art. On Sunday, November 28 at 4 p.m., Zohore, with twelve other artists in black robes, ate pizza and drank wine served on a long rectangular table while being dribbled in bright yellow paint. The performance was intended as a reenactment of Andy Warhol’s “The Last Supper” (1986), a giant yellow recreation of Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous fresco from 1498. The Warhol, a 35-foot-long double screen print of the Da Vinci on canvas, was listed for private sale by the museum for $40 million in early October but pulled off the market on October 28, the date of the intended sale.

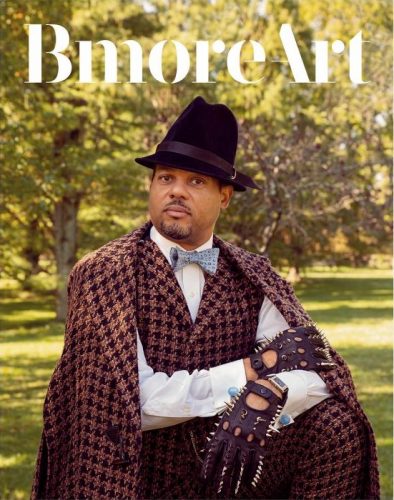

“This is the first time I have ever performed in plein air, specifically outside and also unsanctioned by an institution,” says Zohore, a performance artist and recent MFA graduate of MICA’s Mount Royal School of Art. Zohore has established a record of performing works inside institutional spaces, offering humorous critique and melodramatic spectacle, but in the past, these have always been enacted with explicit consent. This performance, titled “MZ.18 (Endowment for the Future; Last Supper for Baltimore),” marks the first time Zohore has created and performed a critical work outside of these boundaries.

“I came up with the piece the day of the radio show about the deaccessioning,” says Zohore, referring to a WYPR segment where lawyer and former BMA Trustee Larry Eisenstein and I spoke to Tom Hall on Midday about the BMA’s controversial decision to deaccession Warhol’s “The Last Supper,” as well as paintings by Clyfford Still and Brice Marden. “I was sitting in a Trader Joe’s parking lot in a group chat with friends from Baltimore and we were all listening and, suddenly, I was just filled with passion and energy. I wanted to stand up for the artists in this community.”

A complete vision of the performance appeared in the artist’s mind, and he says this is how he typically works. He asked a few friends, casually, if they would mind being covered in yellow paint, and by the end of the day, Zohore had written a proposal and sent it out to a few trusted colleagues in the Baltimore, NY, and DC arts communities, both to gather critical feedback and to fund the project. “It was important to me to compensate the performers for their participation and time,” he says. “By the end of the weekend, I was contacted by Paul Henkel from Palo Gallery, and he agreed to fully fund the work.”