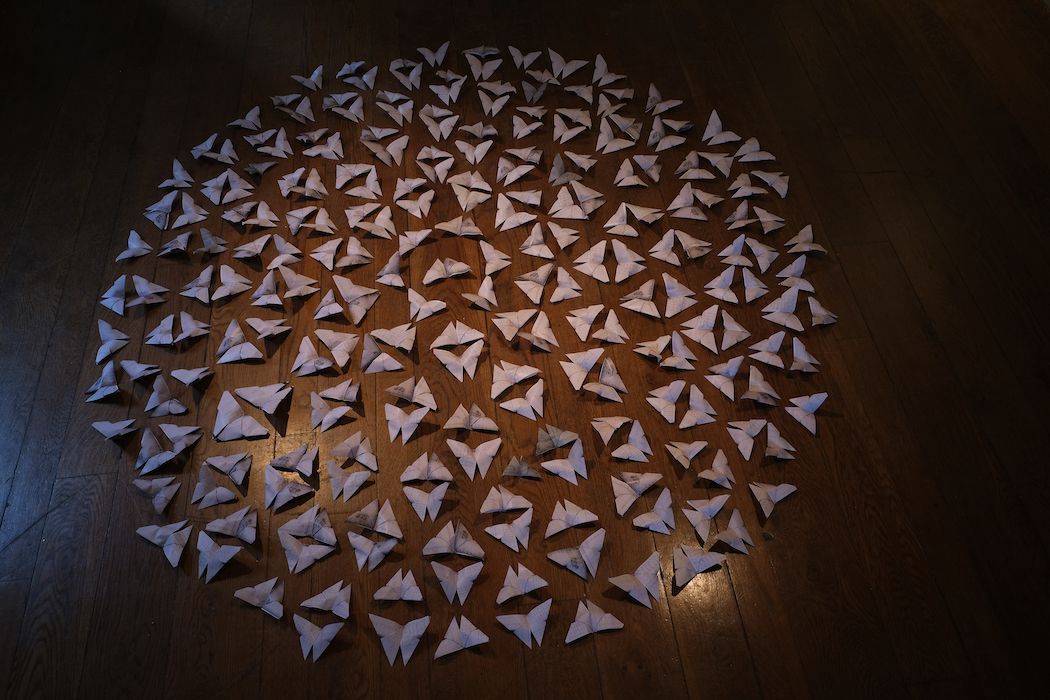

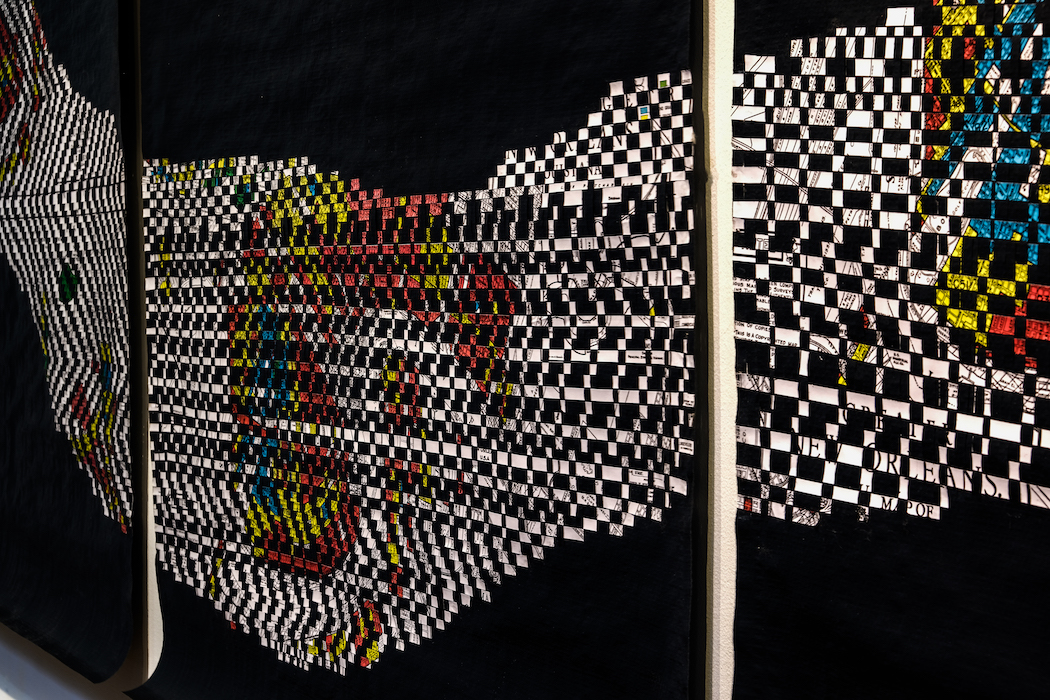

Again and again, confronting these maps, weavings, and tapestries, I’m struck by the labor required by each one. The enormous “White Side,” an extension of the artist’s “Whiteness and Media” series, measures 11 x 19 1/2 feet (or a few inches narrower than Picasso’s Guernica). It utilizes magazine pages backed by Tyvek and hand-woven into an overwhelming field of glitching white faces overlapping and backing one another. Here, the Tyvek creates structural support, but the very nature of hand-weaving all of these white faces together, too—over, under, over, under—reinforces the relationships of power and kinship. Because of the privileges that whiteness bestows within a white supremacist state, white people easily remain invested in it rather than in ceding that position.

As the scholar Christina Sharpe wrote in the essay “Lose Your Kin”: “Whiteness is a political project and it is also a logic, by which I mean it is a calculus, a way of sorting oneself and others into categories of those who must be protected and those who are, or soon will be, expendable.” That sorting does not have to be absolute, I think, and one of the first steps in undoing it, at the very least, requires vigilance of the ways these constructs have limited and harmed everybody.

With all of the repetition and precision involved, Rice’s work offers a meditative way of seeing and making visible the problems of whiteness, which are well-hidden in the mainstream and arguably even more so in “progressive” spaces. This artwork skips the fraught emotionality of white people’s coming into consciousness about the constructs of race and the iterations of racism, and instead leads the viewer straight into an intellectual headspace. Here is a complex and interconnected set of problems, the work shows us, and here’s one way to see and understand them.

That’s another strength in Rice’s work—it escapes the sticky white guilt that slows white people down from meaningfully doing any actual antiracist work, from doing what has been asked of us for years and years. Every protest against police brutality and racial injustice feels louder than the last, and every cycle of awakening for white people feels too late. Everything is dire and needed to course-correct four hundred years ago, or every day since then.

The state-sanctioned murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and numerous other Black people presented a major crisis on top of a legacy of crises in a year utterly defined by crisis. A growing number of people are joining those who have long been demanding radical change, calling for abolishing the police, abolishing capitalism, and securing housing and healthcare for all. The tension is that the people who pull the levers, those with all the concentrated wealth and power, are still invested in the systems that do not serve the majority of people who live in this country. There is so much catching up to do.