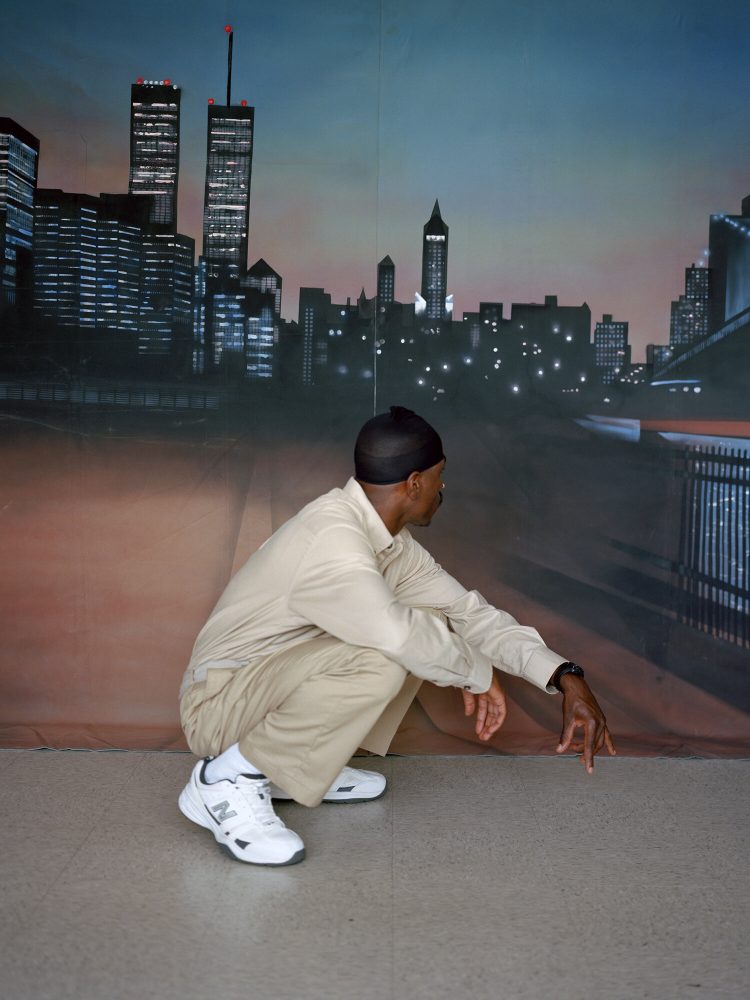

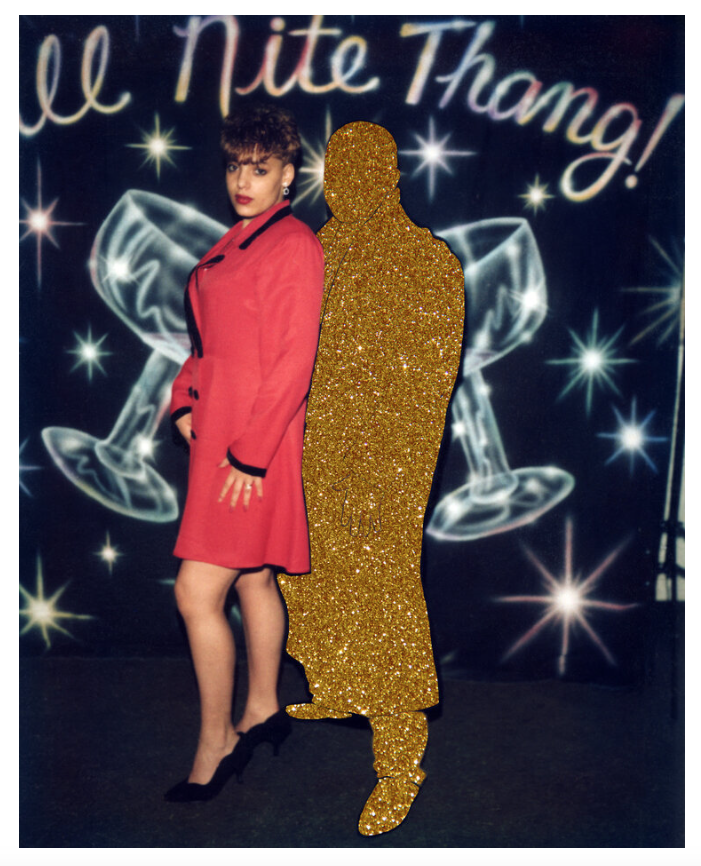

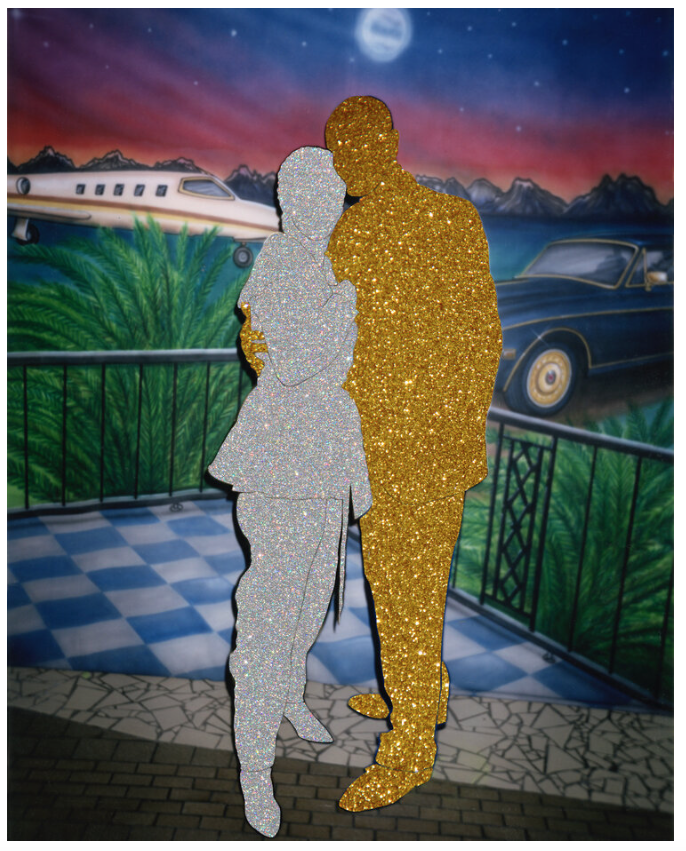

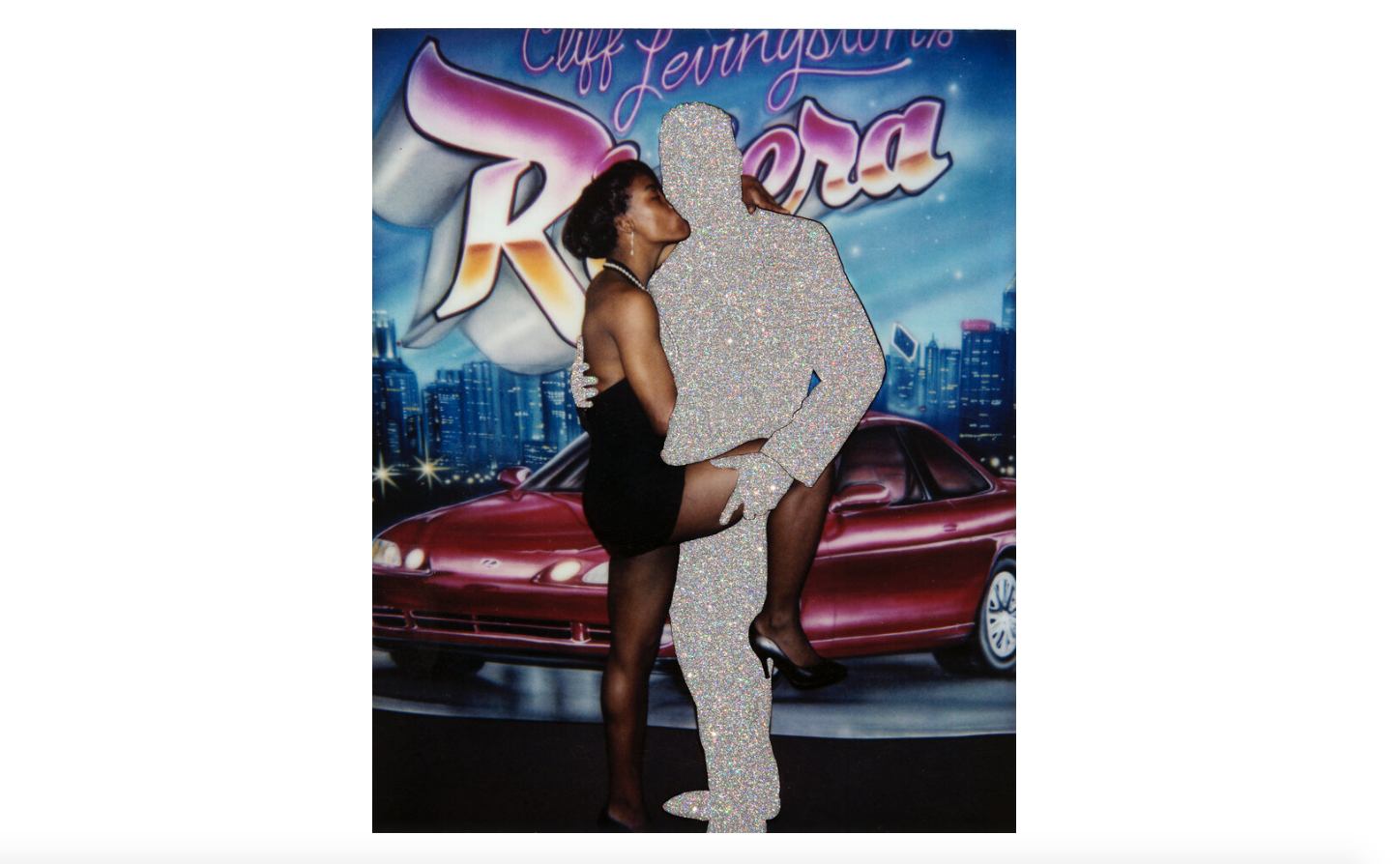

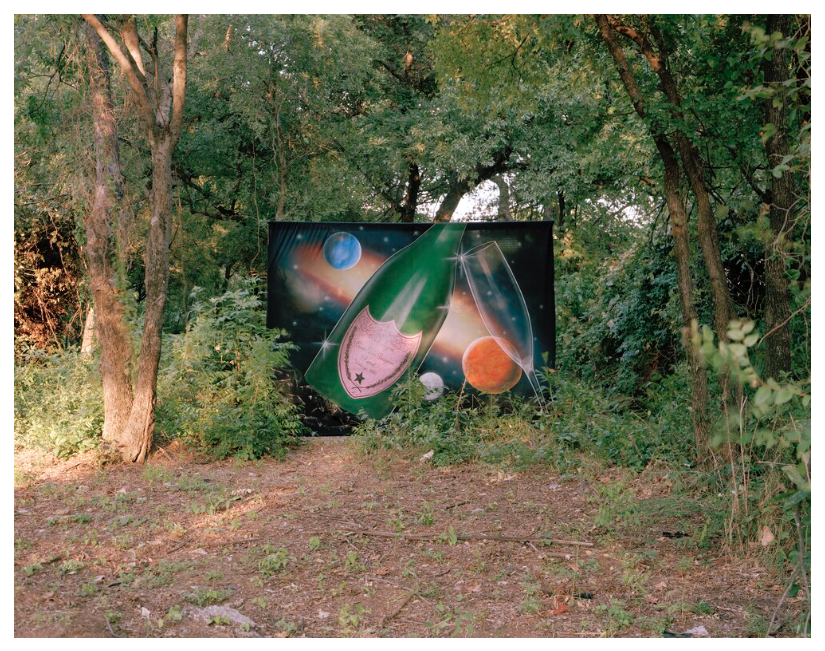

Of all Larry Cook’s photo series, I find The Visiting Room to be the most mesmerizing, but also chilling. Cook depicts Black men in prison culture poses, wearing tan uniforms, skull caps, and Timberland boots in dozens of similar yet distinct images. They model in front of festive, airbrushed photo backdrops of idealized city skylines and expensive cars, the kind used in nightclub photo booths, and each man sits or squats with his back to the camera, eyes seeking impossible escapes through the fanciful backdrops the artist provides. Their loneliness is palpable, but there is hope too. As a person who has visited her own relatives in jail, recalling how heartbreaking it was to visit a person I loved behind glass, Cook’s images conjure up the agony of being in prison waiting rooms: so close, but unable to connect or touch.

Cook is a conceptual artist and photographer, a professor at Howard University, and an archivist based in Washington, DC. His work has been steadily growing in popularity, with a 2020 group exhibition at MoMA PS1 called Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, a 2020 solo exhibition at Weiss Berlin in Germany, and placing as a finalist in the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition at the National Portrait Gallery.

In addition to several exhibits at Galerie Myrtis, Cook was featured in the 2016 Sondheim finalists exhibition at the Walters Art Museum, and he was recently awarded a 2021 Light Work artist residency. Before he became a college professor, Cook worked in nightclubs in DC. The spectacle of having one’s photo taken in front of a photo backdrop has become a primary symbol for the artist, in terms of representing an American Black experience that is powerful and universal in anonymity, placing prison and club photography aesthetics at the center of his practice.