Your work often involves other people, hairdressers doing their craft, or members of the public that you invite to make the work with you. How do you negotiate these working relationships? Do you view the resulting works as collaborative or is it still your artwork? In what ways is that authorship important or unimportant to you?

I would say all of my work is collaborative. Even when I make a static object that is sitting in space, that material didn’t come to me without someone else’s hands or someone else’s interaction. I might not know that person. I have studio assistants and a studio manager who helped me fabricate things. So much is done with the helping hands of Meg Arsenovic, my studio manager, and several other people. Sometimes I’m asking someone with very specific skills to help fabricate things.

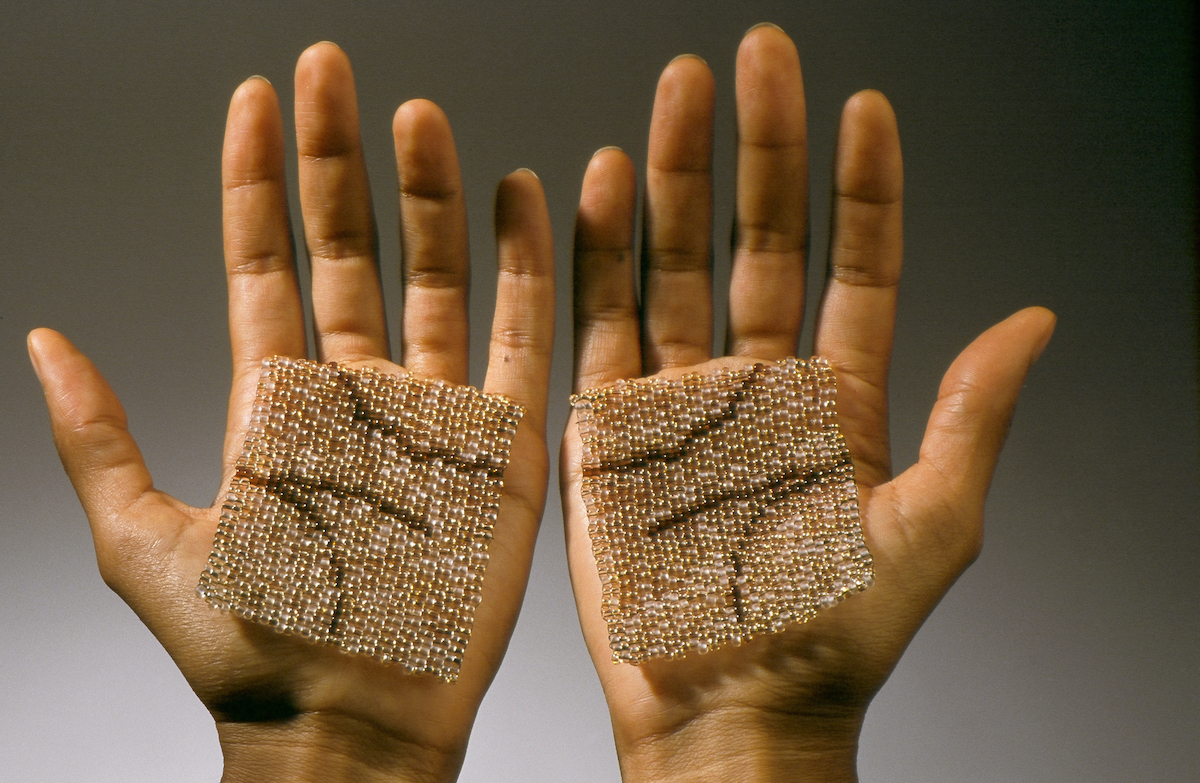

Maybe you’re asking, why wouldn’t all those people’s names [be listed with the work]? With The Hair Craft Project, all of their names were part of the project, and that’s because the point of that project was actually to take the space that I have around being an artist, the privilege that I have about the nomenclature of being an artist, and saying, these women are artists. Here are their names. Here is their work. What I did was provide an opportunity to frame their work. In the case of that project, everybody did my hair. They were paid. They weren’t friends, they’re friends now, [but] they were paid, and paid well. Then they were of course paid for doing the canvases as well. And when the project won prizes, then they were paid again. And when it was sold to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, they were paid again. With that project, that makes perfect sense.

In the case of someone like my studio manager, she gets paid hourly and that’s a different kind of thing. Yes, it is a collaboration, small C, but it’s not my intent or the intent of the work to center her. It’s the intent of the studio for us to be working together to make the work the best that it can be, which means that actually the work is centered. And because it’s my work, my name becomes centered.

There’ve been other times that I’ve done collaborations where the person whose skills I’m bringing in really matters, that they are who they are in terms of the skills that they’re bringing to the table. [For a piece not in the show at NMWA, titled Lingua Franca] I really wanted to indicate ancient Rome. The best material to use to do that was Carrara marble. So I went to a stone carver who is a MacArthur fellow. [I decided,] I need the best stone carver. Nick Benson is one of the best and this is what he does in his work, he studies ancient Roman inscriptions, he has it down. He really understood and championed this work. But he also gets a lot of work where his name isn’t front and center. So he asked me about this, and I said, I will always mention your name with this piece because he chose the Carrara marble. He carved the words, he picked a very specific font using all of his research, and then he saved the marble dust for me so that I could write the word ciao on the floor in the same font. And so in that way, it’s a collaboration, but for that piece it’s important to me that Nick was the person that I collaborated with on the piece. And also, he requested that as well and I was happy to oblige.

There’ve been other times when someone has fabricated a piece for me, but they weren’t really part of the thinking around the piece. They’ve said, can I put this on my website as a piece that I made? And I said, that’s really confusing unless you have a section on your website that says, these are things that I fabricated. You made it and you were paid, but it’s actually my artwork. I never mind when a fabricator has that distinction at all. I’d love for people who are helping me fabricate work to get more attention for the skills that they’re bringing to the table. But then where does the idea reside? If the idea wasn’t yours, then that gets into really tricky territory. But the point is, all of it is collaborative. It’s just different facets of collaborations.

I hadn’t thought about the fact that you have studio assistants, but that makes a lot of sense. The negotiation of making the work with them is definitely part of the work that’s invisible to a viewer seeing it in a gallery. So that’s really interesting to consider.

I’ll say a little bit more about that. When I was at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), chairing the craft department for twelve years, I was concerned that it was an administrative position that would be very demanding. And it was. I immediately thought, I’m going to need studio assistants, at least one, to help me to make sure that the work and my output of the work [doesn’t lag]. The way that I define myself as an artist is that I show work. It’s important to me that the work is out in the world; that’s not the case for every artist, but it is part of my definition of being an artist. I wanted to make sure that the work was in play and out in the world. And I was concerned. That year, I also got a Pollock-Krasner grant for about $25,000. I said this is great because, with about half that money, I could pay someone decently to work part-time with me in my studio. But then I had a better idea, which was to say to VCU, instead of me paying someone $10,000 for working with me hourly, I’m going to pay the institution $10,000 and I want to use it as a graduate stipend and match it with tuition remission. So $10,000 became the equivalent of, in the cases of out-of-state students, more than $30,000. And those were the students who ended up helping me every year.

I sometimes had people for two years, but mostly I had people for one year. That felt better because those—it was almost always women—those women who worked with me were kept out of debt for a year, they were paid a really decent wage, and they were helping me in my studio. It was this mutual benefit.

Wow, that’s brilliant.

Yes. I think it might be the only really smart thing I ever did.