Troubled Waters: The opening of Harborplace sparked a waterfront renaissance beyond Baltimore’s wildest dreams. Four decades later, has the ship sailed for the twin pavilions?

by Ron Cassie

Published August 11 in Baltimore Magazine

Excerpt: Anthony Hawkins is sitting at the amphitheater at Harborplace, between the landmark pavilions he helped establish four decades ago. It’s a beautiful, mid-morning day in late June. He takes a deep breath. There’s hardly a cloud in the sky. Also, hardly a soul in sight. “I’m a Baltimore boy. I’m City College. Morgan. Hopkins,” Hawkins says with emphasis. “My whole family on both sides is from Baltimore. And this pisses me off,” the 76-year-old continues with a frustrated nod toward the faded two-story green pavilions on either side of him. “I don’t know how else to put it.” The last time Hawkins stepped inside the twin pavilions at the intersection of Light and Pratt streets, the busiest in the city, was two years ago. He refuses to again. “Everything is closed off. You have no idea where you are going. I got so angry, it made me physically sick. I had to leave.”

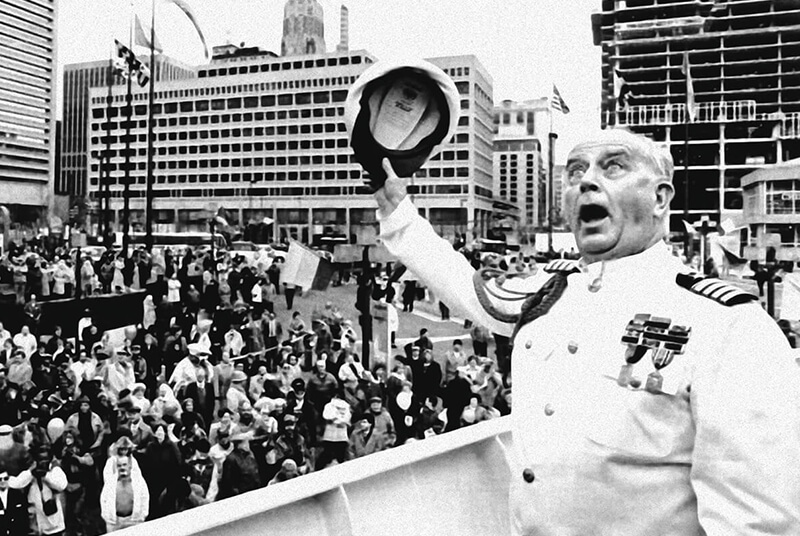

Harborplace is personal to Hawkins. He was the first general manager of the iconic retail and restaurant development, overseeing pavilion operations for 15 glorious years. He’d just built a home, in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and was managing other Rouse Company properties in the region when Jim Rouse himself called to tell him that he needed him to return home. That was 1977. The tall ships had come to Baltimore for the country’s bicentennial the year before, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors, including tens of thousands of Baltimoreans, to the waterfront. Rash Field was still hosting the city’s ethnic festivals and the very popular City Fair then. The “Sunny Sundays” concerts were pulling Baltimoreans to their harbor, too. But other than a promenade, and the Maryland Science Center and World Trade Center, which had both recently opened, little else in terms of built infrastructure existed at the time. Rouse, on the heels of his company’s successful Faneuil Hall Marketplace redevelopment in Boston, intended to change that. “He knew having someone who knew Baltimore to manage it was important,” Hawkins says. “Harborplace was supposed to be for the people who lived here, and it was,” Hawkins says. Ninety-percent of the businesses when it opened had local ties (including a busy comic-book store owned by Steve Geppi, this magazine’s owner). It was the belief of Rouse and former Mayor William Donald Schaefer, who famously cared little about the interests of non-Baltimoreans, that if locals came, tourists were more likely follow. But that was secondary. The point, Hawkins explains, is that Harborplace mattered to the people in charge. “At Rouse, we were hands-on, detailed-oriented. You have to be,” Hawkins says. “Tenants didn’t always like what we did. If you wanted to open a food business, you had to cook for 10 of us, including our food consultants.” The mayor, we know, operated the same way. “I’d get 5 a.m. calls from Schaefer about the trash outside Harborplace, and I didn’t even work for him. I’d tell him, ‘Our sanitation team arrives at 7. We’ll get it.’”