In Repercussions: Redefining the Black Aesthetic, a choir of artists calls you to be still, pay attention, slow down, and savor the glory of a gallery full of Black contemporary art. Curated by Thomas James, this exhibition at the Eubie Blake Cultural Center is an opportunity to recognize a connection between multimedia works by Baltimore- and DC-based Black artists and your own lived experiences. According to the exhibition text, the show “explores the genealogy, spiritual, political, and economic power that objects possess” through media, methods, and meaning that tell stories and reveal personal histories.

A repercussion typically refers to an unintended consequence occurring after a period of time. In the case of this exhibition, it’s looking back to the 1950s and 1960s when Black artists like Sam Gilliam and Ed Clark made work that inserted themselves into contemporary abstract art. Some sixty years later, the artists in this show are again challenging notions of what art can mean, specifically what can be designated as “fine art.” These artists are redefining an abstract Black aesthetic in a time where figurative exhibitions are extremely popular, a clear reminder of Black abstraction’s revelatory and revolutionary power.

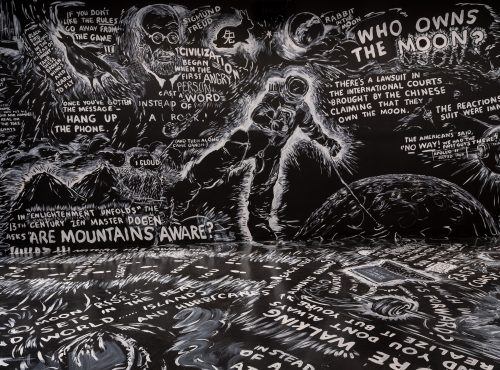

The exhibition Repercussions challenges the viewer to think about the ways in which abstract ideas and forms are represented. The show’s larger focus is material culture, specifically Black material culture featuring objects that contain history and tradition. Techniques like weaving, assemblage, collage, and painting are highlighted, and each thread, brushstroke, cut-out, weave, application, and arrangement of material reifies the idea of creating through memory and ritual.