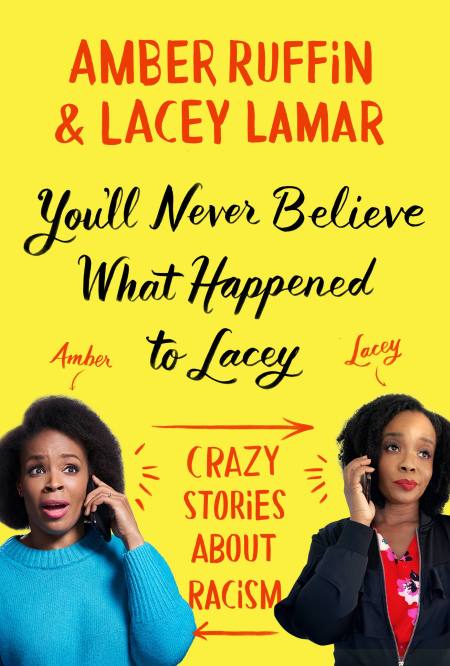

The best book to represent Libra this October is You’ll Never Believe What Happened to Lacey by sisters Amber Ruffin and Lacey Lamar. Now let’s be straightforward, the re-emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 birthed a plethora of books about race, some of them good and some of them . . . meh. However, the reason why You’ll Never Believe rises to the top, for me, is its use of humor. That use of humor comes as no surprise, considering Ruffin was the first Black woman to write for a late-night talk show (Late Night with Seth Meyers) in the United States. Yet, as these two explain in their own alternating voices in the book, being Black in America—much less Omaha, Nebraska, where the sisters were born—is far from easy.

You’ll Never Believe doesn’t wait one minute to start righting that racial balance (a favorite pastime of Libras). In the preface, Ruffin talks about her sister Lamar having checks with Black heroes printed on them. I won’t spoil what happened when Lamar tried to use these checks at a store, but suffice it to say that this is a “firecracker” beginning.

This book takes the sensitive topic of racial justice and serves it to readers with a side of humor. In an early chapter titled “I Got a Million of ‘Em,” Lamar tells a story that many Black folks, including myself, understand all too well—being mistaken for another Black person inside a tourist store and offered free swag. But readers both Black and white will cackle when Lamar admits, “It is not right to take T-shirts that are meant for Whoopi Goldberg. But on the other hand, free T-shirts.”

One of the ways the authors employ humor is by adding visuals to drive some of these points home. “I Got a Million of ‘Em” also includes side-by-side pictures of Lamar dressed up as the various women she’s been mistaken for. And in a later chapter entitled “I want to put this book down and run away from it,” Ruffin recounts Lamar’s story about working at a retirement home where they sell dolls for the elderly in a visitors’ store. Of course, there’s only one Black doll in this store, and Lamar’s co-workers aren’t scared to tell her that this doll looks “just like her.” Ruffin includes the co-workers’ ridiculous statements, like “Didn’t I just see you in the gift shop? How’d you get here so fast?” But for extra emphasis, there’s a picture of this fluffy-afroed doll, next to an equally ridiculous greeting card, that looks nothing like Lamar. As they say, sometimes a picture’s worth . . . .

While I thoroughly enjoyed this book, it may not be for everyone. Sometimes the comedy borders on tragedy, especially when you think about how many times Lamar quit jobs for the ways bosses or co-workers made her feel uncomfortable. It’s important not simply to see this book as entertainment, but also to understand that this is someone’s life, and these microaggressions—some of them macro, in my opinion—have economic implications too. That said, I do believe in the power of humor to change hearts and minds. Langston Hughes wrote about this in Not Without Laughter; he began to create a legacy for Black folks to explore our pain in another way. And whether it’s like Richard Pryor, Whoopi Goldberg, Key and Peele, or Wanda Sykes—Ruffin and Lamar make a wonderful addition to the pantheon of Black artists using humor.