For about 45 minutes last Saturday evening, I sat on the floor of what once, about a century ago, was a factory, watching a group of people labor together over a shared, enigmatic task.

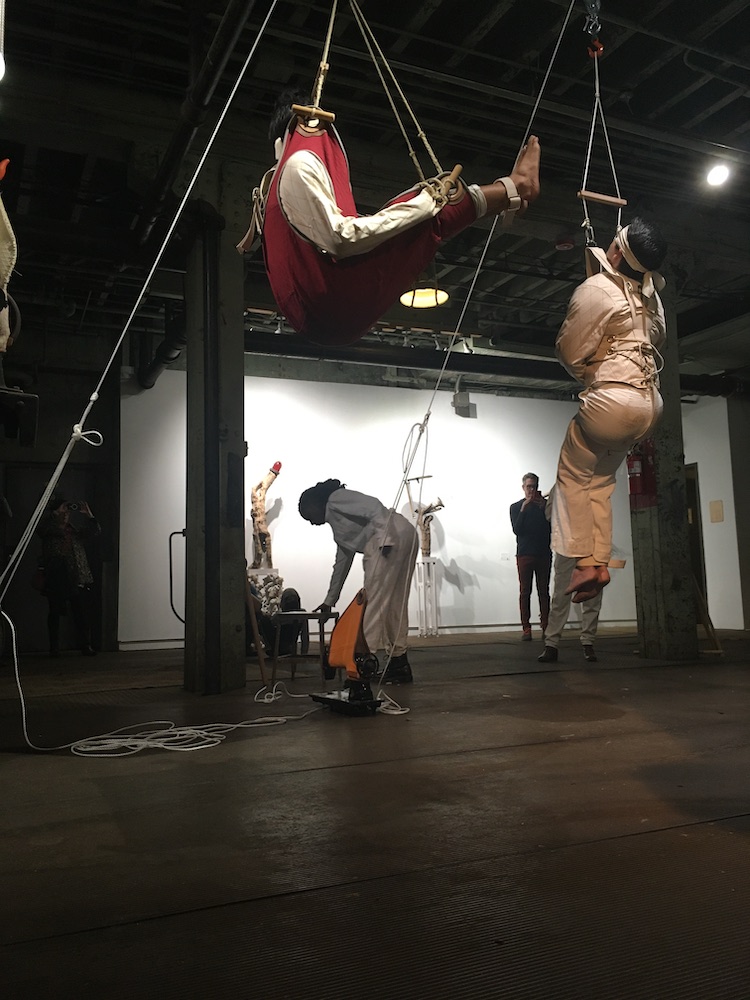

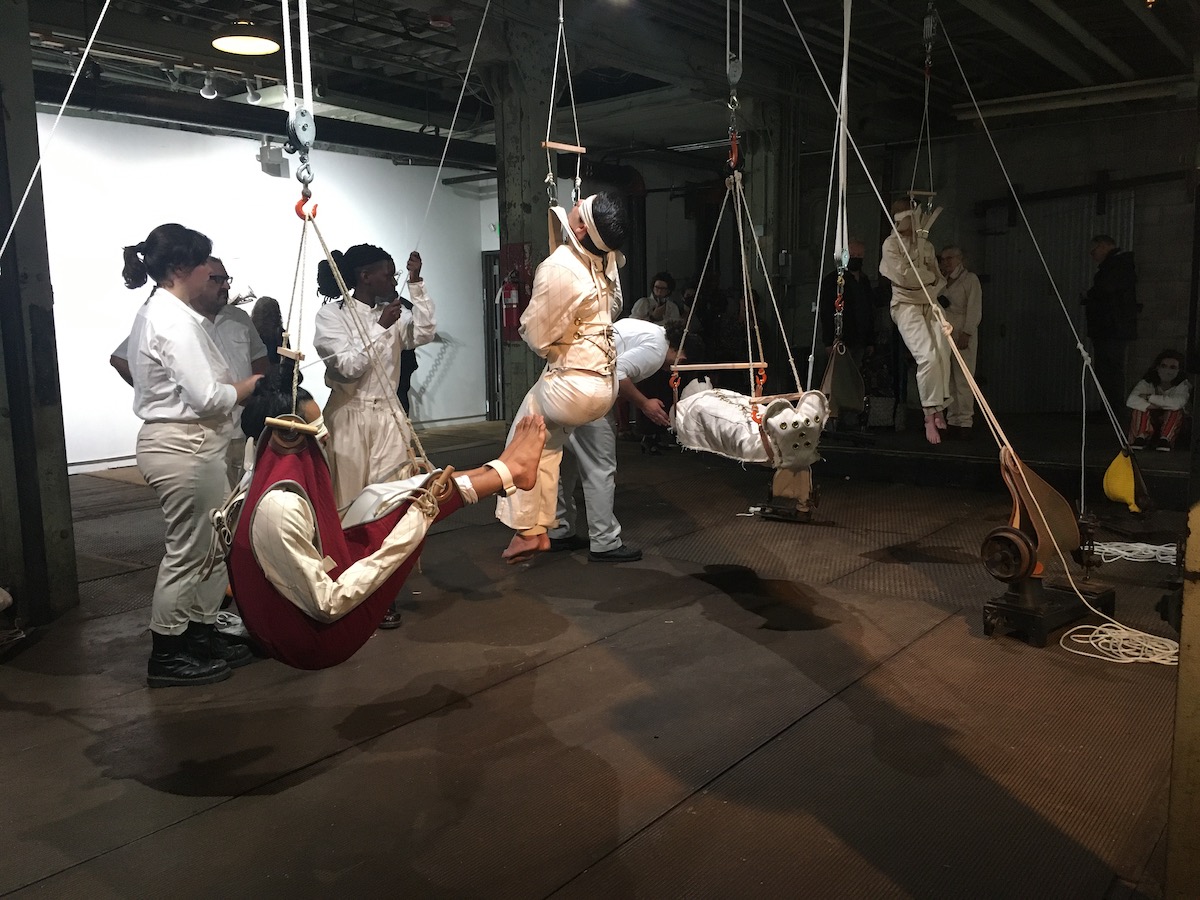

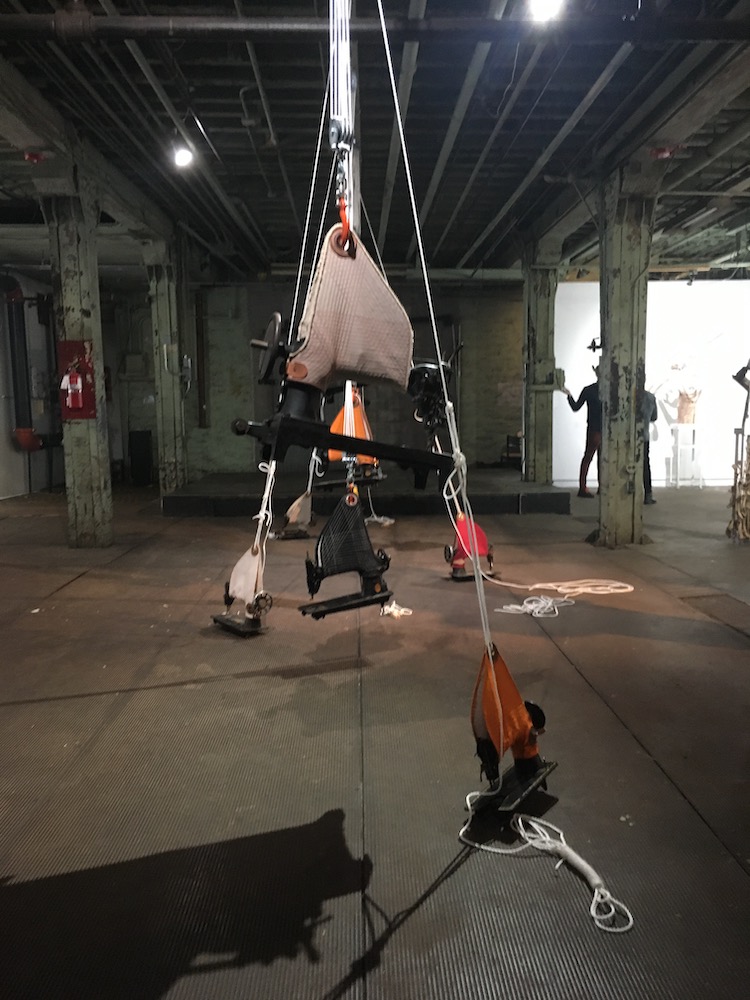

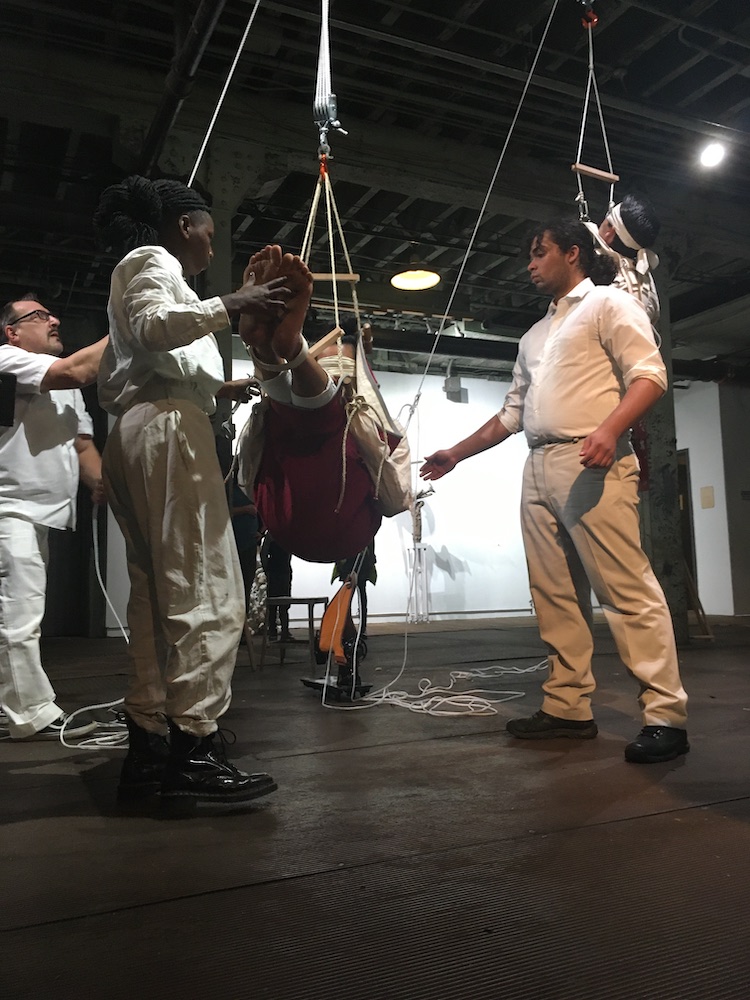

In David Page’s performance One hundred years without progress, four people in all-white attire methodically lugged four other blindfolded, bound, and costumed actors into Area 405’s gallery, one by one, setting them on the floor like hunks of meat. The workers were focused and goal-oriented, but not at all robotic, as they carefully rigged each individual into a complicated system of pulleys and weights, with ropes and knots and O-rings and hooks, before hoisting them into the air. Periodically, they noticed an issue and made adjustments, letting someone down and fixing their straps and slings to allow for better respiration or bloodflow, untying and retying a knot, or tidying an excess of rope.

Except for occasional cranking and clanging, the production was basically silent, the workers communicating mostly through body language, finger snaps, and whispers. The performance, created and orchestrated by Page, who was also one of the bodies costumed and lifted into the pulley system, was a tribute to the oft-hidden but critical choreography of the laborers who produce all the mundane items we depend on.