“We couldn’t be more thrilled to partner with Pussy Riot this year.”

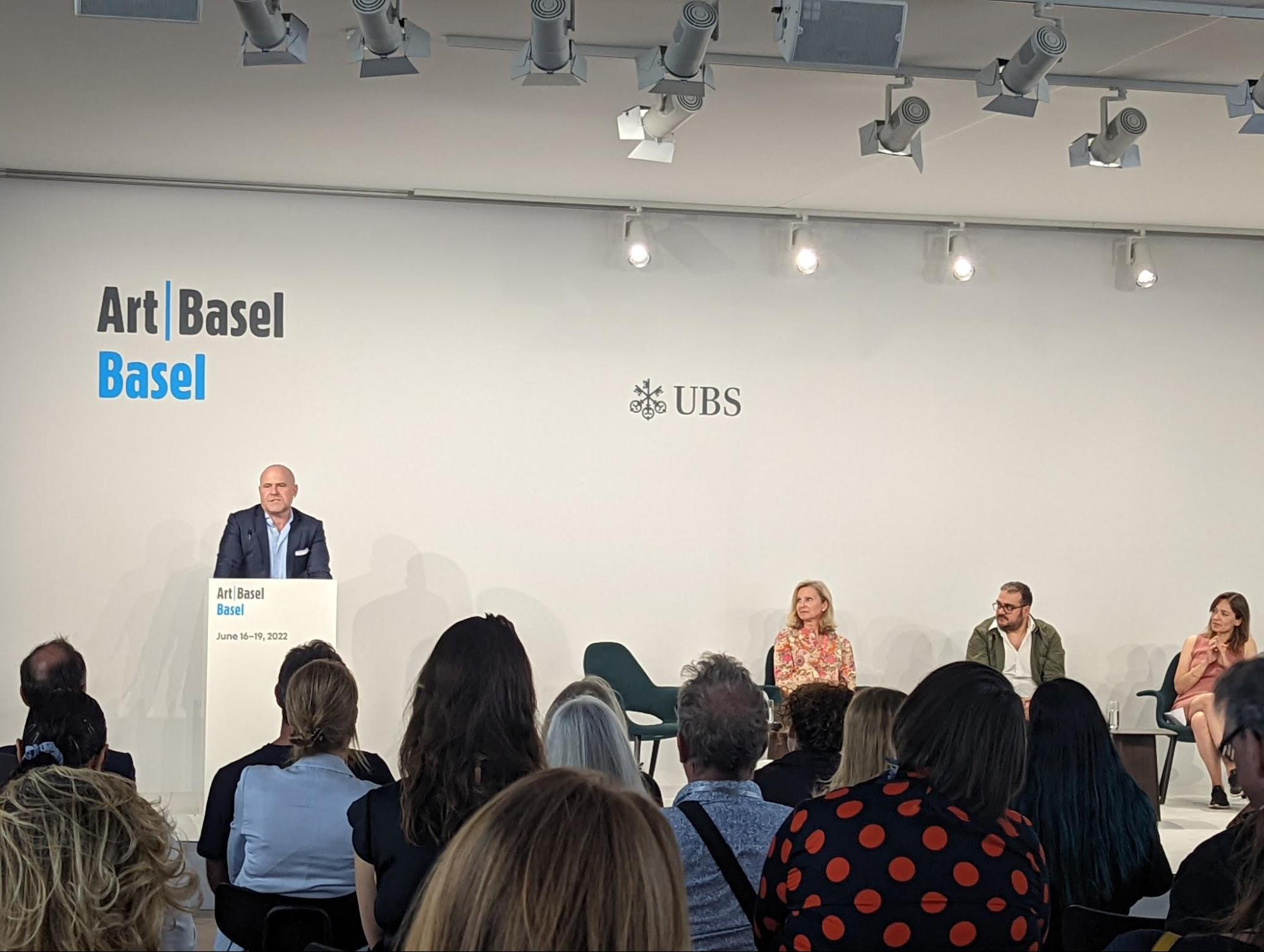

No, that quote is not from a meme mocking corporations’ annual June-time pinkwashing campaigns. It’s from Marc Spiegler, Art Basel’s Global Director, at the fair’s media reception last week, hours before the anticapitalist feminist punk band played a sold-out concert to benefit refugees, sponsored by the art fair. Spiegler, for his part, seemed genuine in his enthusiasm for a more politically relevant version of the consummate commercial art world event, now in its 51st year.

Last week the Swiss fair returned to its normal summer dates after two years of disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. But Spiegler—who took the fair’s reins in 2019, shortly before the world was upended—doesn’t believe Art Basel should return to business as usual. “Let’s be clear, these are still not normal times,” he explained, before litanizing the multiple crises rocking Europe and the world at large, from climate change and the war in Ukraine to the mass displacement of refugees, and inequality exacerbated by all of the above.

It’s not what I expected to hear at the panel discussion. I assumed most other art journalists would arrive with questions about economic insecurity and inflation’s impacts on the art market. But when someone in the audience asked whether famously neutral (or complicit, depending on one’s politics) Switzerland’s unprecedented sanctions against Russia would negatively impact sales to oligarch collectors or exclude Russian artists, the Art Basel leadership seemed to bristle at the poor taste of the question. “Obviously no one should be judged by the nationality of their passport,” Spiegler declared to murmurs of approval, but he clarified that the fair had purged known Putin supporters from the VIP invite list. That’s a one-percenter slap in the face that surely stung more than a whole Monaco marina of impounded yachts.