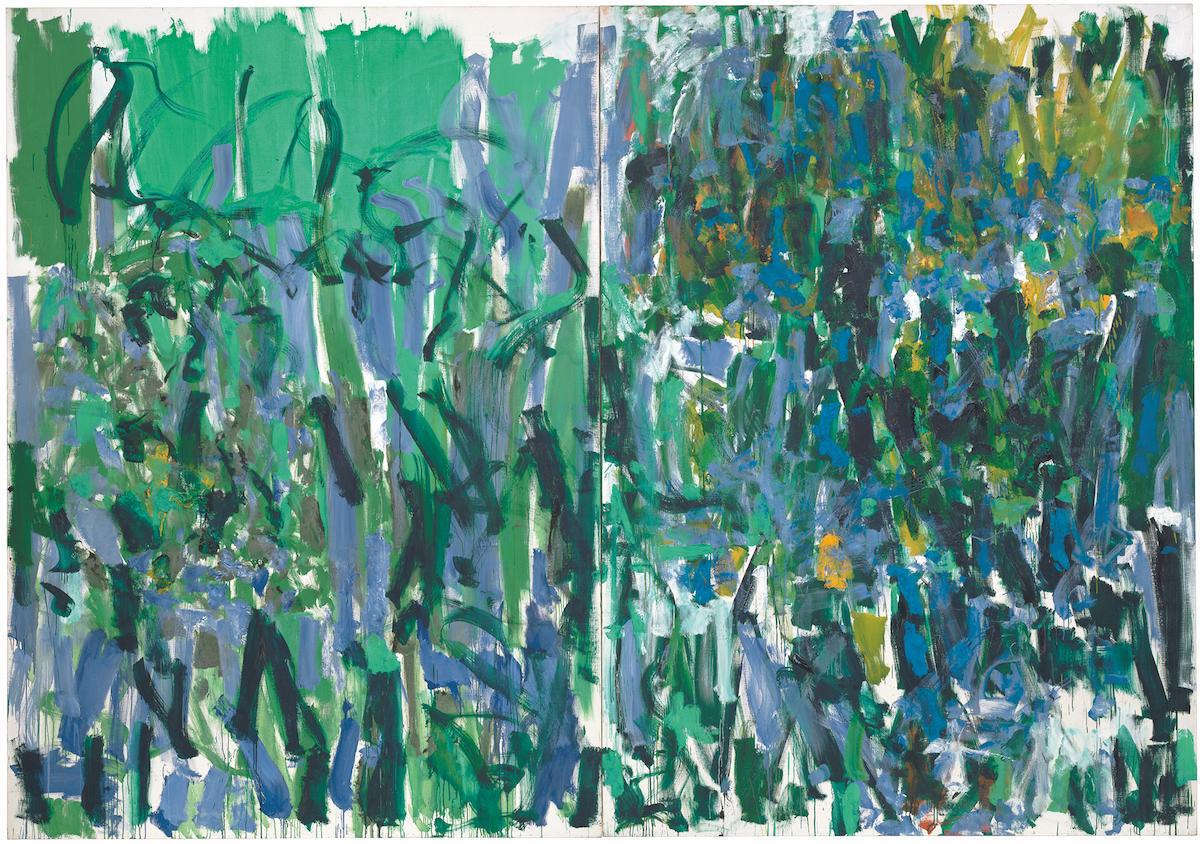

In the United States, Joan Mitchell is recognized as a major figure of Abstract Expressionism. Emphatically branded as American during its postwar heyday, AbEx remains emblematic of the values this country claims to represent: freedom, individualism, innovation. These were the cowboys of painting. Mitchell, born in Chicago in 1925, not only produced the large, gestural abstractions to fit the bill (her gender notwithstanding); she had a brazen character with heavy drinking habits and coarse language to round out the all-American image.

But on the other side of the Atlantic, Mitchell is recognized less for her paintings’ affinities with the work of Willem de Kooning and more for the influence of Monet and Van Gogh. As much as those of us stateside like to associate Mitchell with the New York School, the reality is that she spent more than half of her life and much of her career in France. She even owned the estate home to Claude Monet’s cottage in the French village of Vétheuil and was included in the Biennale de Paris in 1959, a seal of her qualification as a “French” artist if there ever was one. She died in Paris in 1992.

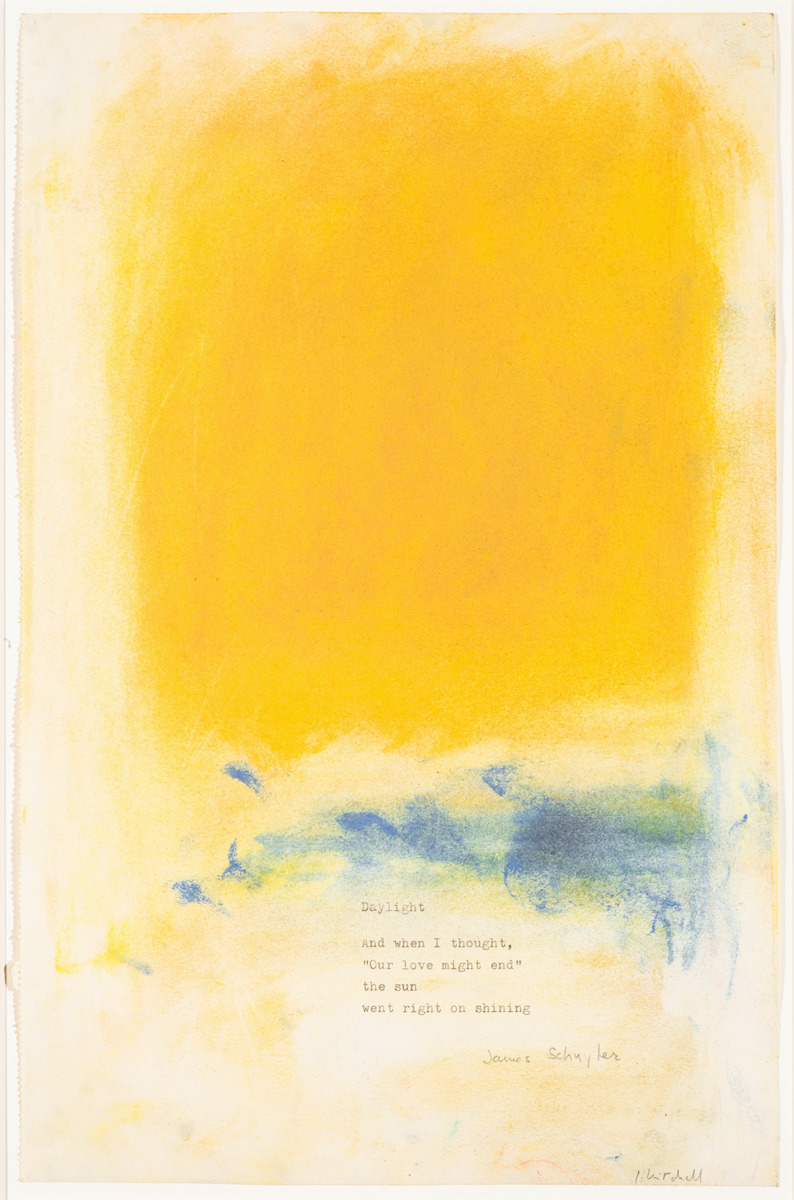

So, appropriately, the three-stop touring retrospective, titled Joan Mitchell and currently on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art, began in the United States (at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) and will end in France (at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris). But the lack of consensus surrounding her legacy makes for shaky ground for a curatorial team to cross. It’s also an opportunity to denationalize art history—a massive project that the retrospective’s curators (the BMA’s Katy Siegel and SFMOMA’s Sarah Roberts with the help of a team of researchers) by no means started or fully achieved.