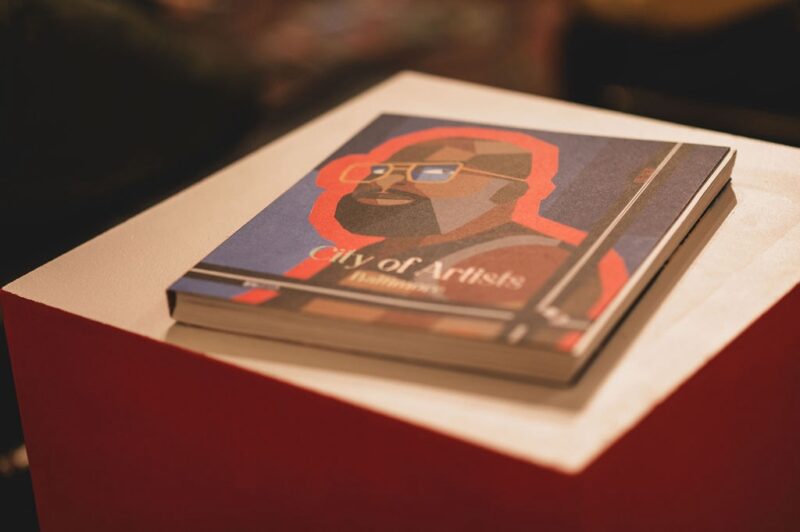

There are certain kinds of people among us, ghost-world travelers who experience near spiritual moments in the presence of the things that Ben Riddleberger likes. Others might call the stuff junk, but to Riddleberger it’s treasure—usually chipped or dinged and often rusting. “When another row house comes down in Baltimore, hardly anyone sheds a tear,” said Riddleberger. “But there are things inside those houses that are a crime not to save.”

To list the items that Riddleberger has saved from landfills would take a building as large as the 1885 gas company “valve house” in South Baltimore where he keeps his collection of curios: an architectural salvage business called Housewerks. All 8,000 square feet of it.

“They made gas from coal here,” he said of the edifice built by the Chesapeake Gas Company, a forerunner of today’s BGE. “They’d compress the gas and send it out to a third of the city.”

Riddleberger purchased the building from photographer Al Fiterman in 2004 and opened for business the following year. Since then, repair, restoration, and commerce have taken place below a vaulted roof topped by a clerestory. Photographer Dean Alexander had a studio there before Riddleberger bought it. “It took us hours to paint the ceiling with industrial sprayers,” Alexander said. “When you’re up there, the place looks like a football field.”

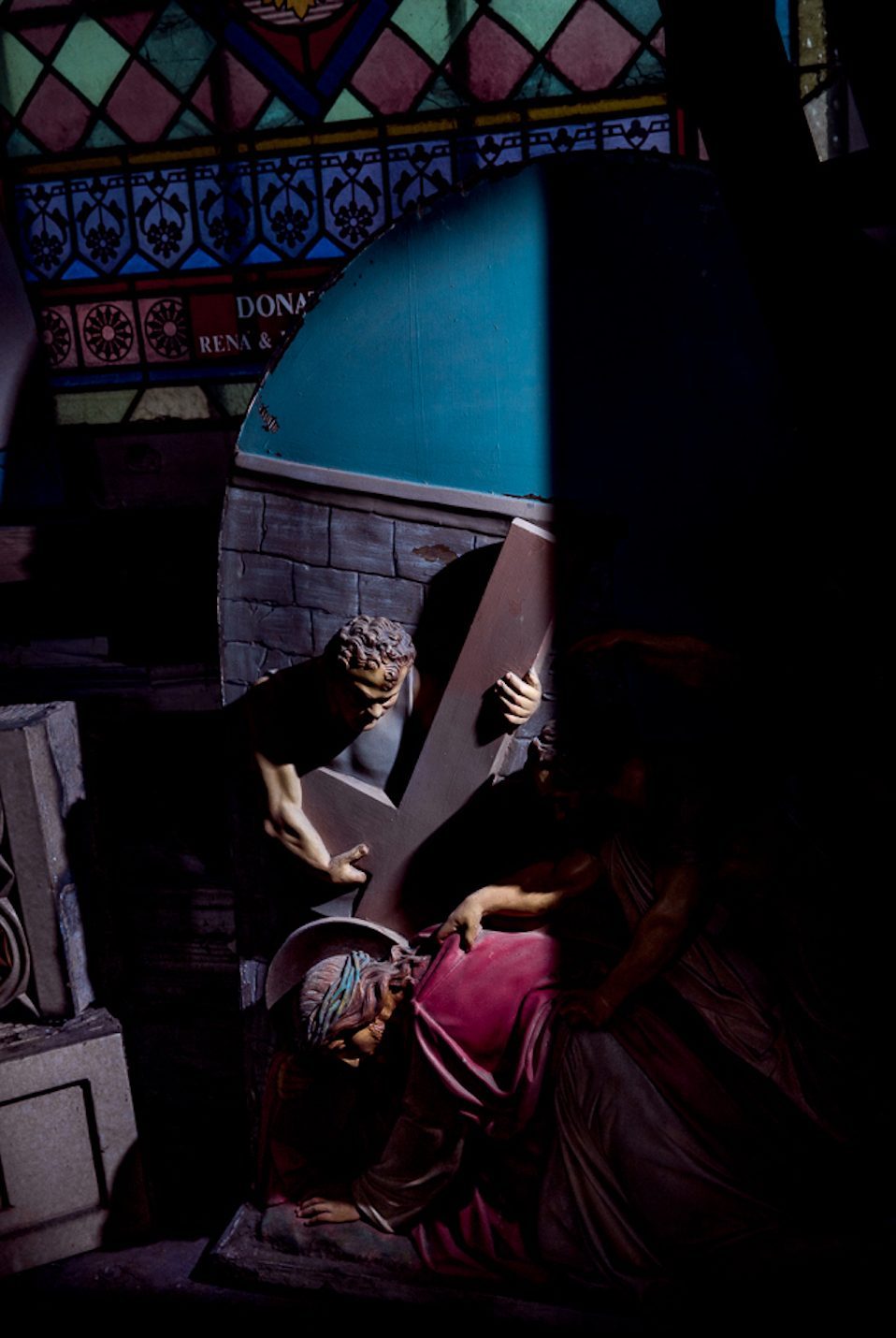

Shafts of sunshine bathe stained glass from a Federal Hill church demolished for townhomes, a crystal chandelier with dozens of dangling baubles refracting the light and oddities like a 1950s pedal car for kids. “Great lines, I’ve never seen a model like it,” said Riddleberger of the vehicle. “It’s got four wheels and a kid’s license plate from Mississippi dated 1953. I bought it from [an antique] picker years ago.”