Thirty minutes from the Canadian border, an organic farm in Pembroke, Maine, harvests blueberries, cranberries, and mushrooms from its orchards. The Smithereen Farm cultivates the land, but it also works to replenish its acres to preserve natural ecosystems. Underneath this biodiverse landscape, the cellar of the Smithereen farmhouse stores 20,000 core samples, cylindrical mineral extractions used by miners to assess the presence of precious metals.

“I will never, ever forget the first time I went down there,” recounts artist Stephanie Garon. “It was flickering lights, a deep stairwell, [and] leaking, seeping water coming in.” The core samples stored at Smithereen Farm date as far back as the 19th century, when Pembroke became a prominent mining center. Located two miles away from the farmhouse, a mine known to locals as “Big Hill” represents both the remnants, and active pursuits, of prospectors’ attempts to acquire natural resources.

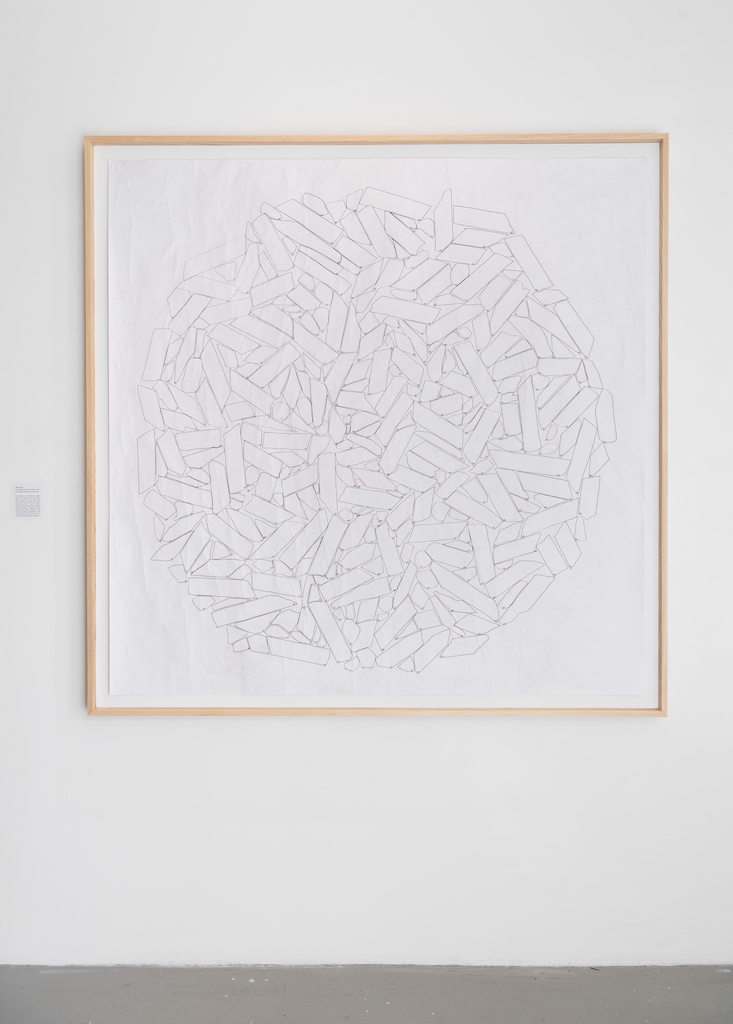

Garon is an environmental artist whose paintings, sculptures, and installations explore humanity’s complex relationship with nature. Her new solo exhibition, Gold Rush, uses materials previously extracted from Big Hill to examine the ecological, cultural, and social implications of mining land that Indigenous tribes, including the Passamaquoddy, have inhabited for more than 12,000 years.

Throughout her career, Garon has experimented with organic materials, often treading the line between art and environmental science. “Being immersed in nature, and being surrounded by metal, were my earliest forms of language,” she says over a Zoom preview tour of the exhibition. The artist is a fellow of Hamiltonian Artists, a nonprofit that advocates for accessibility within the contemporary art community. The organization operates out of Hamiltonian Gallery in Washington, DC where Gold Rush is displayed.