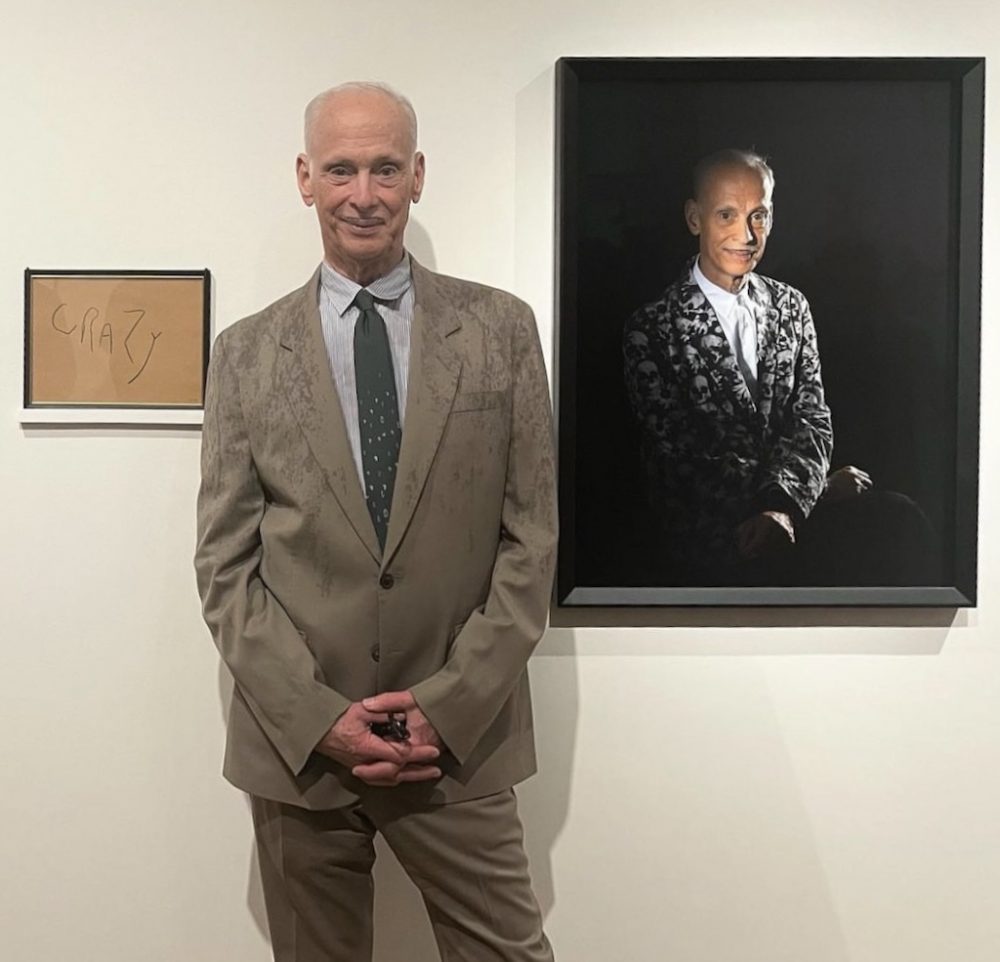

Last year, John Waters gave his hometown some of the art world’s best news in recent memory: he’s leaving 372 artworks from his decades-spanning private collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art. But fans won’t have to wait for the Pope of Trash’s sede vacante to enjoy some of these gems.

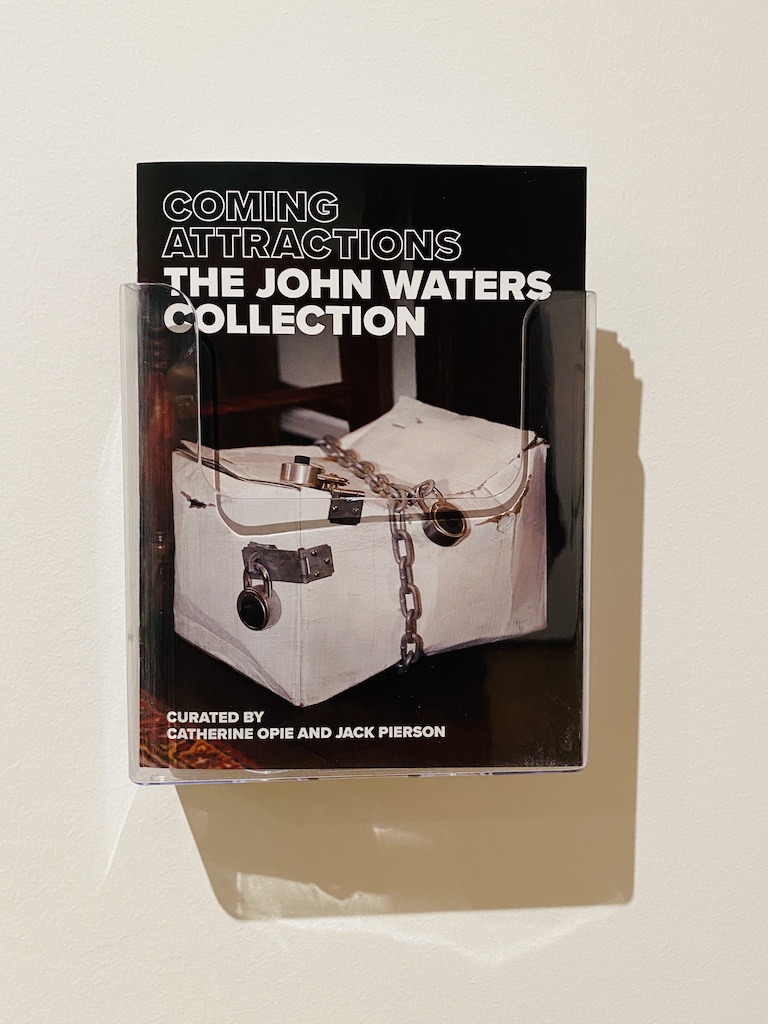

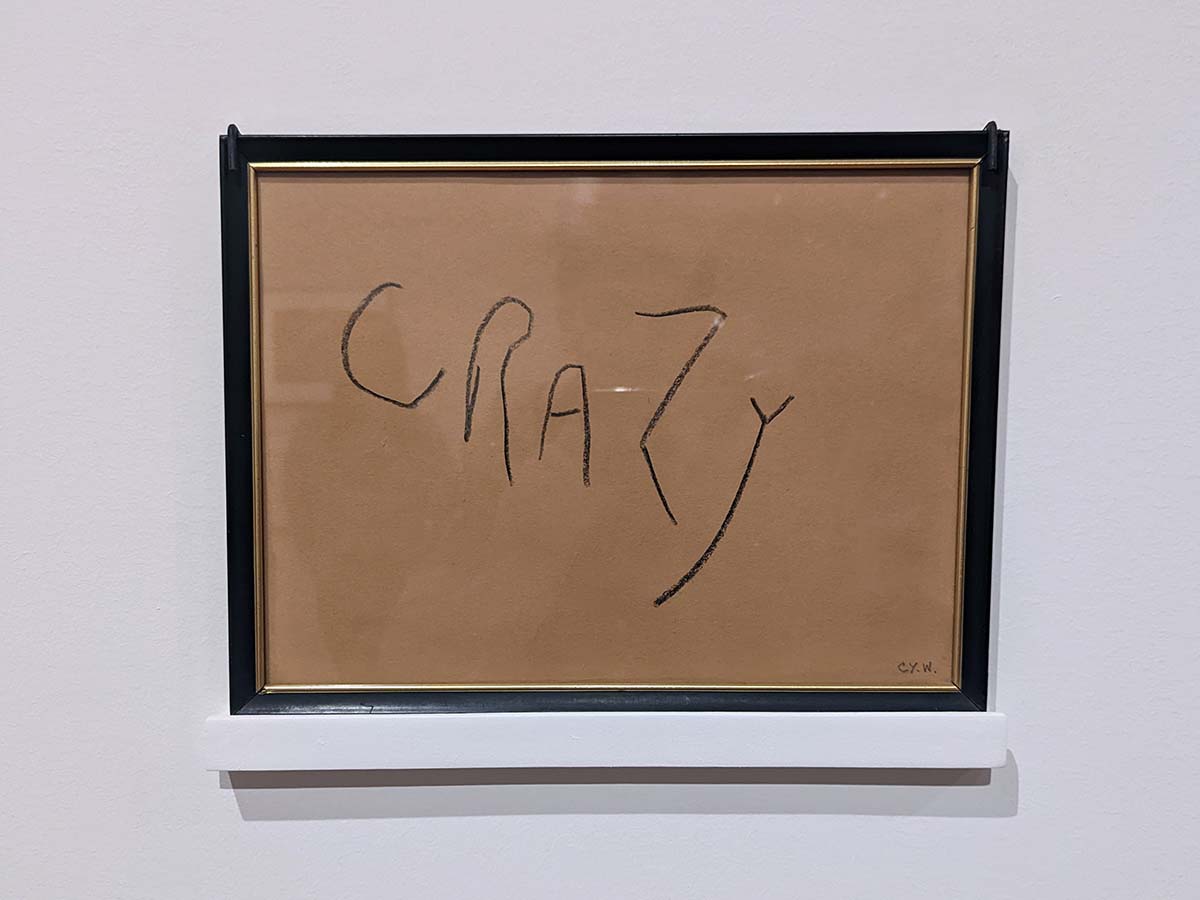

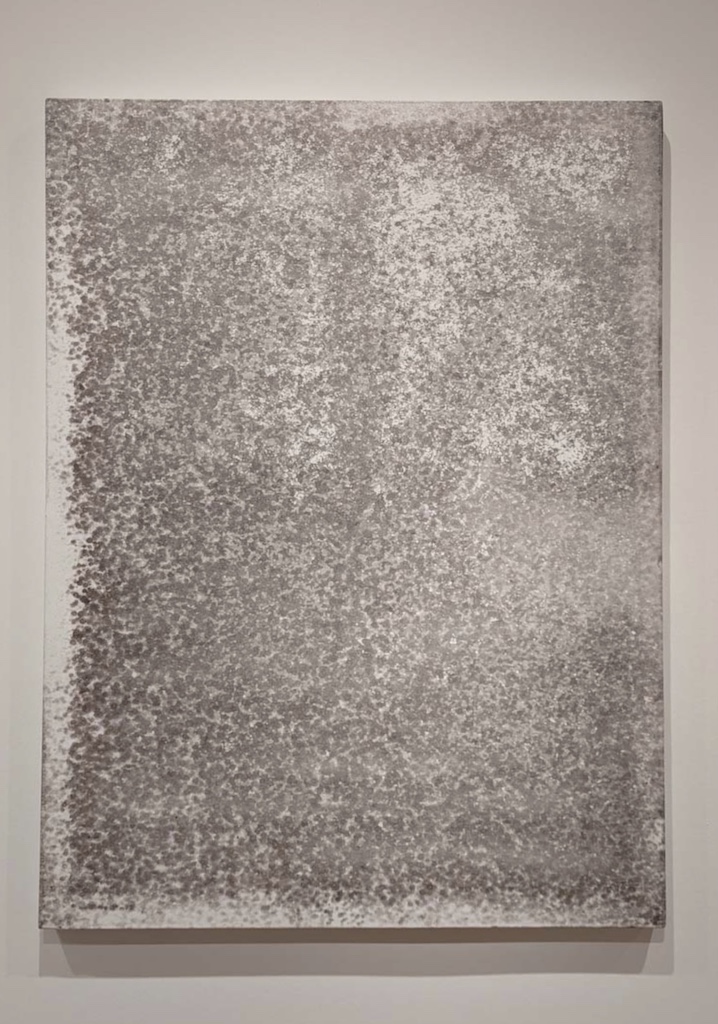

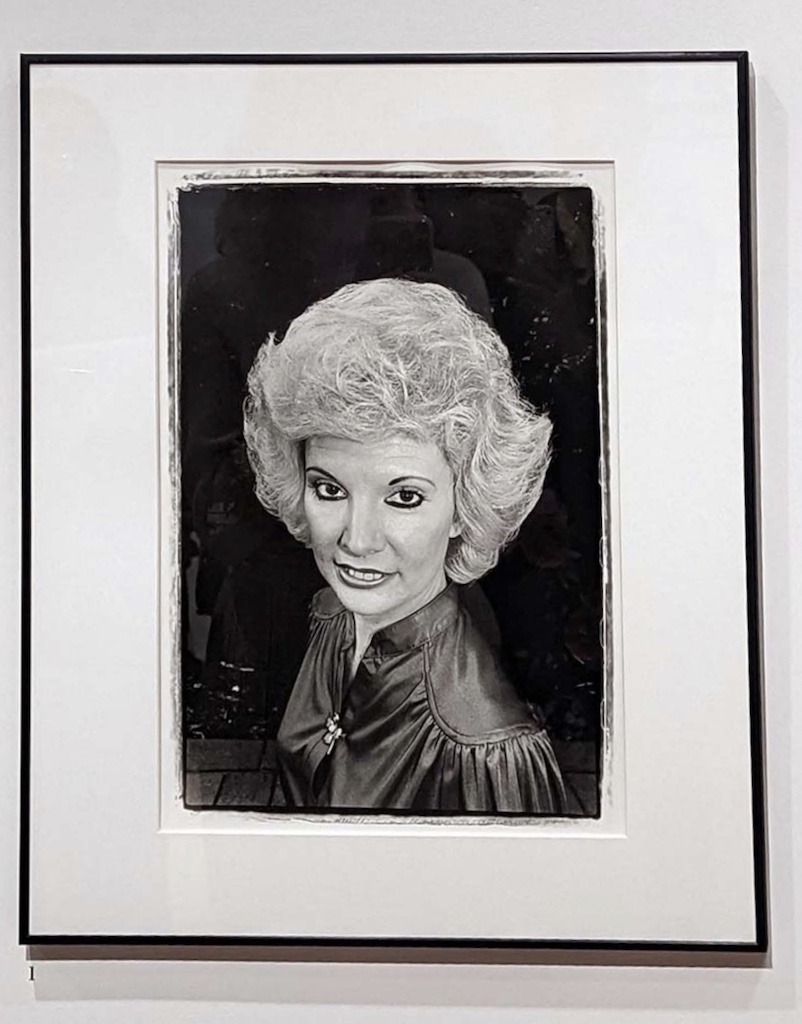

In Coming Attractions: The John Waters Collection—which opens Sunday in the BMA’s Nancy Dorman and Stanley Mazaroff Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings and Photographs—roughly 90 works from the singularly subversive bequest are on view for your perusal until April 16. The exhibition includes pieces by Cy Twombly, Mike Kelley, Nan Goldin, Andy Warhol, Diane Arbus, and Waters’ own father.

The exhibition is guest-curated by internationally renowned queer artist Jack Pierson and photographer Catherine Opie (who I, personally, first discovered after she was immortalized in Le Tigre’s feminist punk anthem Hot Topic!). It’s a testament to both their curatorial chops and friendships with Waters himself that they’ve put together a show that feels cohesive, intimate, smart, and unrepentantly funny.