“America is a place of opportunity and upward mobility for some people, but not for everyone,” said Darren Walker, President of the Ford Foundation, at the Mississippi Museum of Art (MMA) on April 9, 2022. “If we cannot solve these problems in the South, we cannot fix America.”

This statement came out of a panel discussion hosted by the MMA, where Walker and exhibiting artist Mark Bradford discussed the potential for contemporary art to address historic American issues of inequality, many of which are typically associated with Southern states’ histories of slavery, Jim Crow, and anti-Blackness, but are not unique to the South.

The exhibit, A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration, curated by Jessica Bell Brown (BMA) and Ryan Dennis (MMA) features new work by twelve Black American artists exploring their own historical and familial relationship to the Great Migration. It has now moved from the MMA to the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) as a co-curated project, on view there through January 29, 2023. Although it’s installed differently and Baltimore offers a new context for the research-driven work, Walker’s statements made during the opening weekend in Mississippi are no less potent: The South’s problems remain at the core of America’s problems as a whole.

The Great Migration, a movement of six million Black Southerners to the North and West from 1916 to 1970, is a central American story but it has been largely undocumented by historians, archivists, and left out of art history, with Jacob Lawrence’s Great Migration Series existing as a singular standout—until now. Movement is a groundbreaking exhibition about the promise of upward mobility and the sacrifices endured by Black Americans to realize a safer and more stable life. It is also an opportunity to consider our collective past, present, and future through the personal lens of family history from those who experienced it directly.

Movement features newly commissioned works by American artists with Southern ties selected by Bell Brown and Dennis. Each artist was given significant support and time to research their own family history in relation to the Great Migration in order to create new works of art about their discoveries. The process took over a year and included globally recognized artists (Mark Bradford, Theaster Gates, Carrie Mae Weems, Robert Pruitt), as well as rising stars (Leslie Hewitt, Allison Janae Hamilton, Torkwase Dyson, Stephani Jemison), of whom a handful are affiliated with Washington, DC and Baltimore (Jamea Richmond-Edwards, Akea Brionne, Zoë Charlton, Larry W. Cook).

The site specificity of Southern roots against the backdrop of American history, as well as the personal nature of this research, lends a palpable sense of fresh discovery, a sense of newness and energy if disparate stories—perhaps forgotten and neglected for many years but now sparkling and bright refreshed from this deep digging—endeavor into our own murky and circuitous pasts, lost names and places, purposefully forgotten or hidden traumas and bitter disappointments, resignation to live better and do better, to leave it all behind.

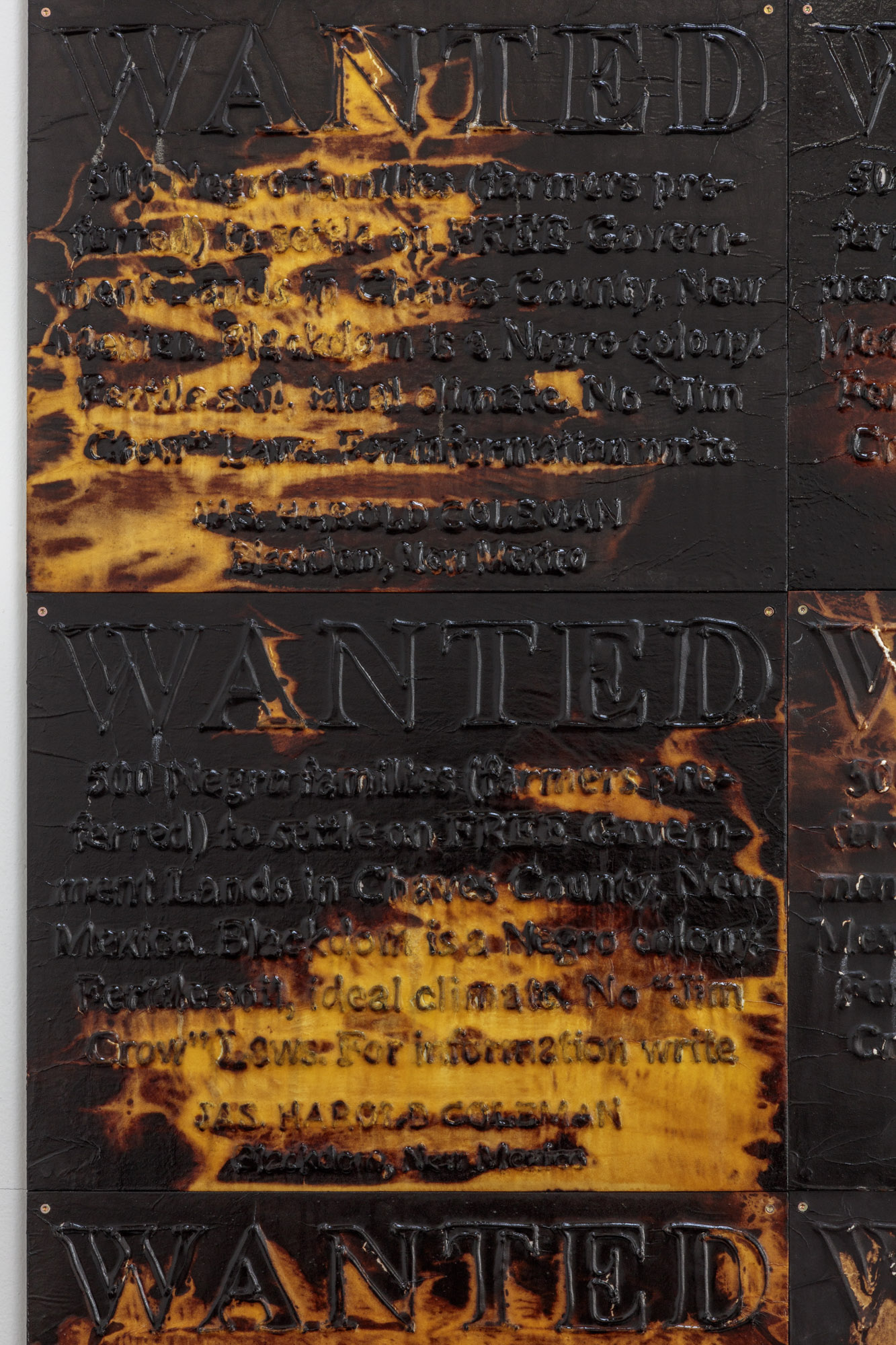

The artists are not only creating innovative constructions and beautiful objects to look at, they’re rewriting their own history, based on research. As part of this intensive process, the participating artists traveled to ancestral lands, looked up old records and newspaper articles, dug into scrap books and keepsakes in dusty boxes and in attics and basements where objects, documents, and photos of unfamiliar faces were unearthed. The surprises came from revelations about their own family members, from finding stories they always believed were just rumors, and understanding why it all came to happen. The sum total outcome of the exhibit is that these artists, and with them the audiences who see the show, can feel more connected to the past and each other, part of something much larger.

I traveled to Jackson, Mississippi for three days in April 2022 for the opening weekend to experience the exhibition within the context and culture of one of America’s oldest Southern cities, and amongst the artists, curators, and supporters for whom this exhibit is extraordinarily special. Now that it is displayed in the BMA’s cavernous Thallheimer gallery, it’s fascinating to see these works not only installed differently to create a nuanced narrative, but to witness Baltimore City audiences’ enthusiastic response to it, even our collective sense of claiming ourselves to be a part of the Upper South, just shy of the Mason-Dixon line.

***

At the Baltimore Museum, the curatorial team was afforded a linear space with glistening concrete floors, in which they could plan a progression with a succinct beginning and end, compared to a radial design at the MMA, where a circular focus placed sculpture in the middle and spaces for film at the edges.

Rather than attempting to tell the story in a chronological or literal fashion, at the BMA the works are installed based on formal characteristics, where visual cues and material culture riff upon one another and the three video installations are given different treatments, although each is cinematically displayed in a unique theatrical space.