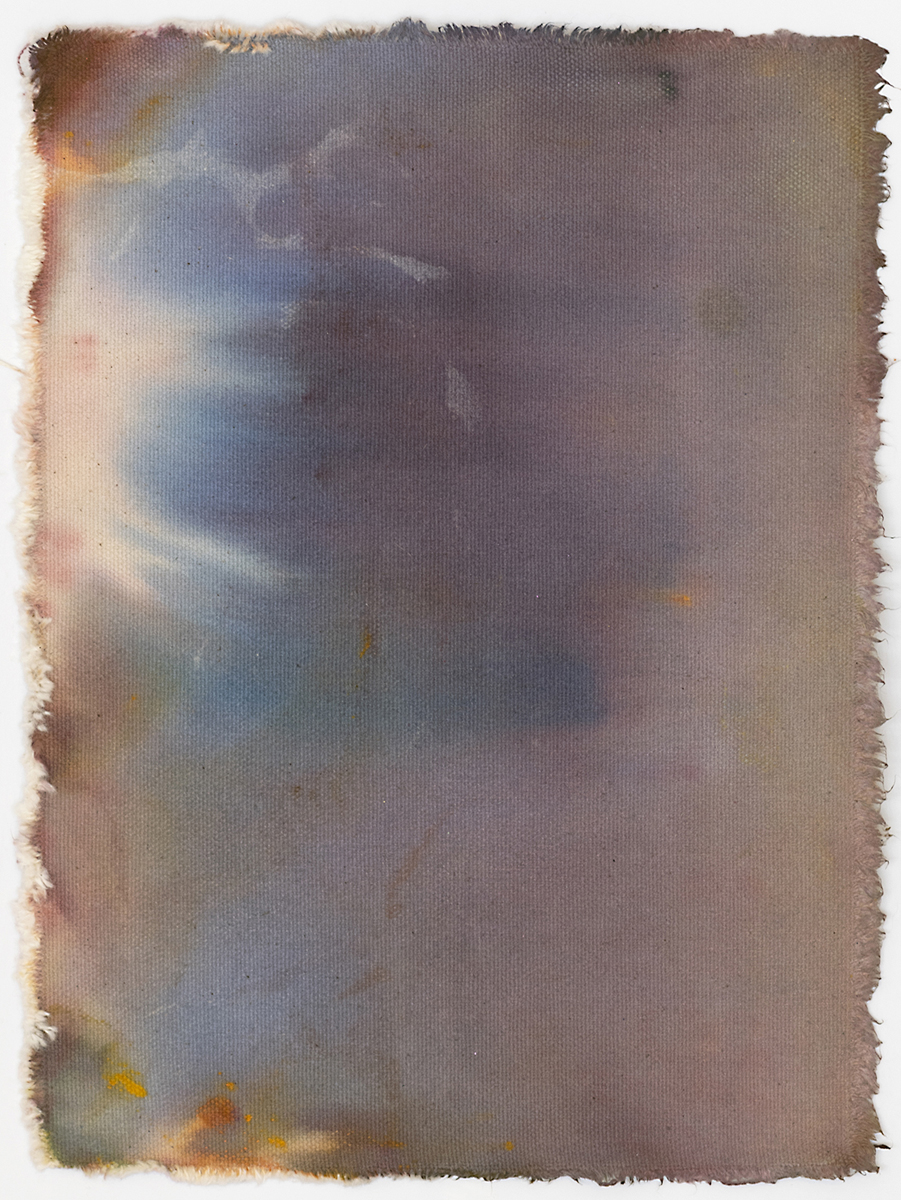

I was surprised by your poems because at first I assumed that—based on the introduction about the Dublin Mountains and a cursory glance at your paintings—I expected that there would be a stronger link to “landscape” in a more traditional sense. And then I was so pleasantly surprised by the way that you treat the textures of domestic space as a landscape—not necessarily your own domestic space, but the idea and texture of intimate interiors.

I just love that line, “there’s a part of the architecture that dreams of being outside.” I feel like with all of your poems I could be reading instructions for—or even visualizing—stage setting for a theater or a screenplay. And I really love the way you can capture a landscape sensibility for an intimate scale of space. Does that make any sense?

That’s interesting because I guess I grew up inside a lot. I wasn’t so much the kid that went out and ran in the mountains with the other kids. I was a bit more introverted and I’d stay inside drawing in my room. I would go out and enjoy it, but a lot of my early experience of landscape was through a window. And then my mother and my aunties in particular had, you know, the way maternal figures in Irish families tend to—well, not all, I can’t generalize about everyone… I’m saying the ones I had—my mother and my aunties collected a lot of decorative things.

[Laughs] Oh God Yeah!

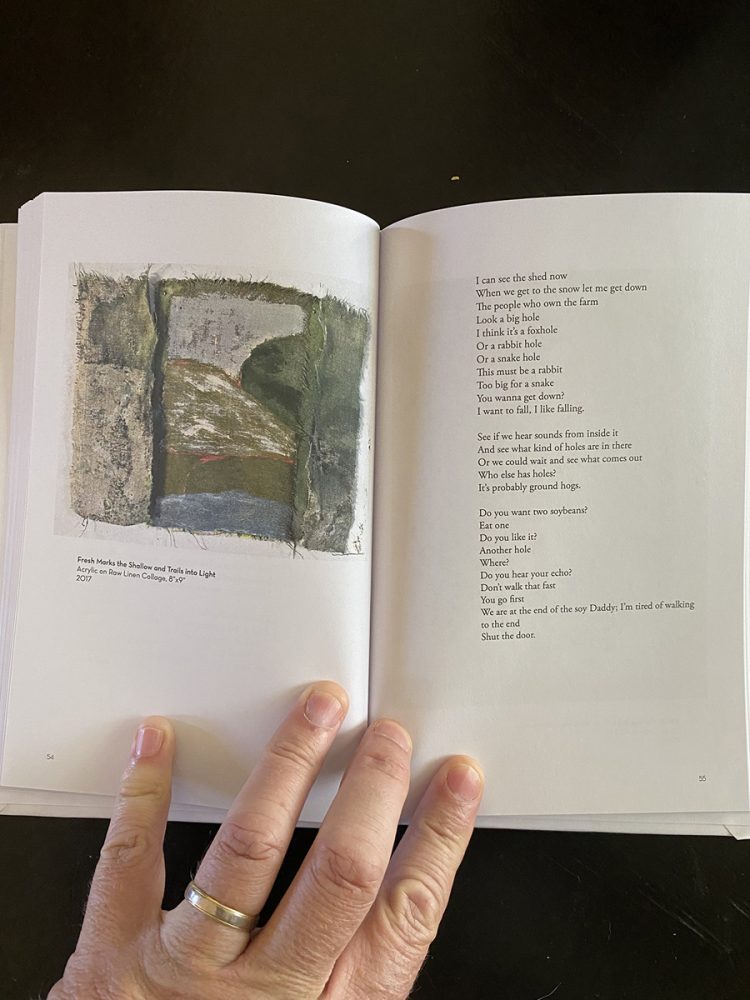

The graphic designer who did the book, Fred Murray, calls it “bric-a-brac,” like, just useless stuff that looked nice, you know? So my aunt’s house was full of little porcelain cups for the tea and the decoration for them.

A pattern on every teacup, and a saucer and doily under every teacup…

So I guess my imagination—when I go back and remember them—I remember that as much as the landscape. Or I remember the landscape through the window of that space. Part of me wishes I could do a series of interior paintings and I haven’t quite done that yet.

You mentioned that poem about my auntie’s sundials, but then my poems mention my mother’s decorations as well. One of the first poems I wrote was written sitting in my parents’ house looking at this stuff and saying, “Wow, this really reminds me of her. She might have passed away, but she’s still here with all this stuff… she left all this stuff here…”

Like what do you leave behind in the world? I guess I’ll leave behind a storage unit full of paintings or something. But my mother left behind all this decorative stuff that she collected…

Just yesterday I was trying to explain the Irish horror vacui in domestic space! Like, our families fill every surface with something! Every plate has to have a print… wallpaper on every surface! And it’s so funny to me because I’m such a minimalist! I hate having decorative things! But your poems just remind me so much of being a child and being in family members’ homes. In childhood I remember the strange sense of interior spaces having this weird double connotation of claustrophobia but also possibility and play…

Yeah. Like you almost want to get outta them in a way.

And you capture that so well! I just thought so much about my own childhood and family and things while reading your book. And I don’t know how much of that is cultural or how much of it is that you have this ability to like to capture something so specific that the specificity then becomes almost universal because it’s so salient and real…

That’s nice to hear because when I was writing them I was mainly sharing them with friends and family who were relating to them. And I was like, “You know the only people who are gonna enjoy this are people who knew me… people who grew up with me.” I felt that way ‘cause they’re so specific, but it’s nice for you to say that. I guess putting the book out, I’ve realized that people have related to it who knew nothing about my past. But you know, your sister’s always gonna like the poem you write about your mum and dad. Right?

[Laughs] My sisters might not! But I was just visiting my family while reading your book, and on my last day I wanted to absorb as much of it as possible, because it made me think of my own relationship with my parents so much I wanted to leave the book with them. But I’m such a “book” book reader—I love having the physical object—so it was bittersweet to leave it with my father to enjoy. He loves poetry too, and especially Irish poets, so I know he’s really going to appreciate your work and the ways you play with language.

Can you talk about how you apply rhyme or rhythm or not in your poetry? Because I always found myself caught off-guard when the rhythm of a poem would change or shift or suddenly would emerge out of something that was less structured. I really enjoyed that as a reader, but also wanted so badly to be hearing them read aloud.

I think they’re still kind of spoken word poems. When I’m writing them, I’m hearing my voice in my head saying them. Some of the rhymes are to do with the way I pronounce a word more than it being a genuine rhyme. So it’ll kind of be a half rhyme. Then when I’m really feeling like I’m in the zone with the poem—and this doesn’t always happen—but sometimes I have this idea that I’l actually control the reader through the rhyme.

I’ll sort of say, “Hey, certainly, look: now I’m rhyming, but I wasn’t rhyming at the start.” So I use it to change the mood of the poem. That’s one of my favorite games to play in poetry… the sort-of half rhyme or rhyming words that shouldn’t really—you wouldn’t necessarily think of rhyming. But if you start in a prose format and then end with a poem that rhymes, it’s almost like poems-within-a-poem. So I kind of like that idea.

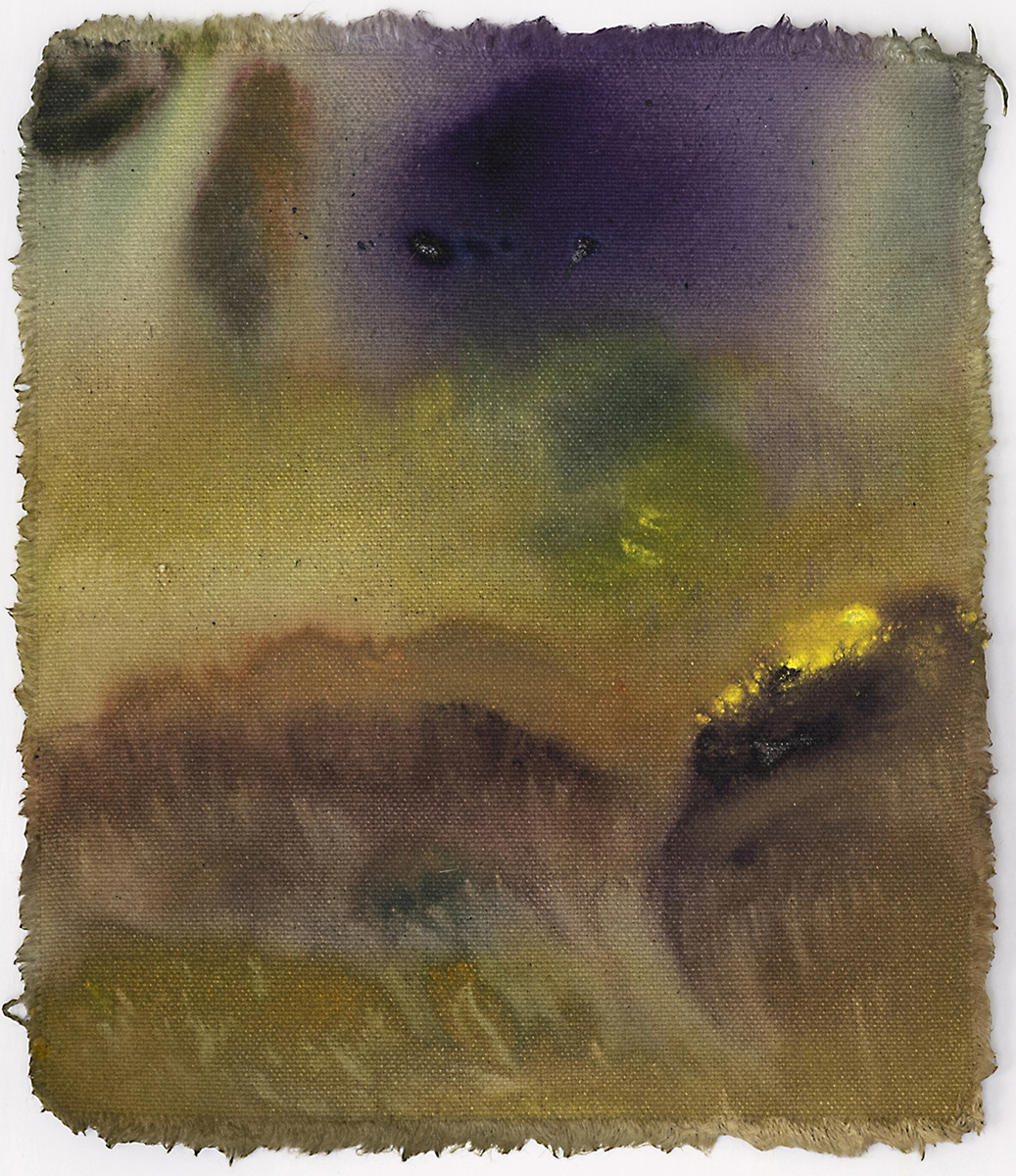

I think that also relates to your paintings. Especially in some of your compositions, there are really lovely moments where the texture or size of brush strokes will shift and almost zoom the viewer’s attention into a detail set across a very lyrical background. I suppose that’s actually kind of a nice summation of both the book in terms of both text and imagery?

Yeah, the space of the paintings kind of comes from growing up in the mountains. Like the view of the city from the mountains was expansive. So that’s always been the sort of space—but then where you can zoom in on the potted plant on your table or whatever. Not that I put potted plants in the paintings! But you know, that wide view and then the closeup. That’s interesting. I hadn’t thought about that, but maybe the certain parts of the poems are closeups.

Maybe there’s a bit of a cinematic eye or to both? It’s interesting that so much of your practice grew out of experimenting with video. It’s almost like you’re filling in the sensory gaps that cinema can’t quite capture, using other media…

Yeah, I always think I’ll go back to video one day. I definitely enjoyed the video camera when I came out. When I was in undergrad my parents bought me a video camera as a present when I graduated. I had so much fun with that…. just filming moths on the walls, you know, stuff like that.

Speaking of gifts parents give you, I keep coming back to this one line in “Perhaps I Ought.” I think it’s a nice sentiment to end on:

“I always think of how I needed a father, but rarely of how you needed a son…”

You just capture the complicated dynamics of family so well…

It was definitely a complicated relationship with my dad and I never had that thought—it never came to me until he was passing, when he was sick—it was like, “Oh, he needs me as well.”

I think a lot of Irish people have complex relationships with their families. And for a lot of Irish sons, it’s with their father. You know, as a kid it seems like they’re always there for you, they’re your dad.