Initially published in 2004, Thinking with Type was groundbreaking in the way that Ellen combined text/type and imagery to tell the story of typography. It’s a bestseller that has been published in several languages, and Ellen is working on a third edition of the book now. “Whenever a young designer hands me a battered copy of Thinking with Type to sign at a lecture or event, I’m warmed with joy from serif to stem,” Ellen wrote in the introduction to the second edition. “Those scuffed covers and dinged corners are evidence that typography is thriving in the hands and minds of the next generation.”

Born in Philly and raised in Baltimore, Ellen has an identical twin sister, Julia Lupton, at the University of California, Irvine, with whom she published Design Your Life: The Pleasures and Perils of Everyday Things.

Ellen earned a BFA in 1985 from Cooper Union, where she met her husband Abbott Miller. The two lived in New York City for fifteen years. She started working at Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian Design Museum, in 1992 as a full-time curator.

A couple of years after their son was born, Ellen and Abbott moved to Baltimore. She went to part-time at Cooper Hewitt, and took on a teaching position at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in 1997. She co-founded MICA’s MFA in Graphic Design program in 2004 with Jennifer Cole Phillips, and currently serves as the Betty Cooke and William O. Steinmetz Chair in Design.

Ellen worked between NYC and Baltimore for more than two decades. After 30 years at the Cooper Hewitt museum, her term ended in 2022. She is looking forward to focusing on her books, lectures, and traveling in addition to teaching.

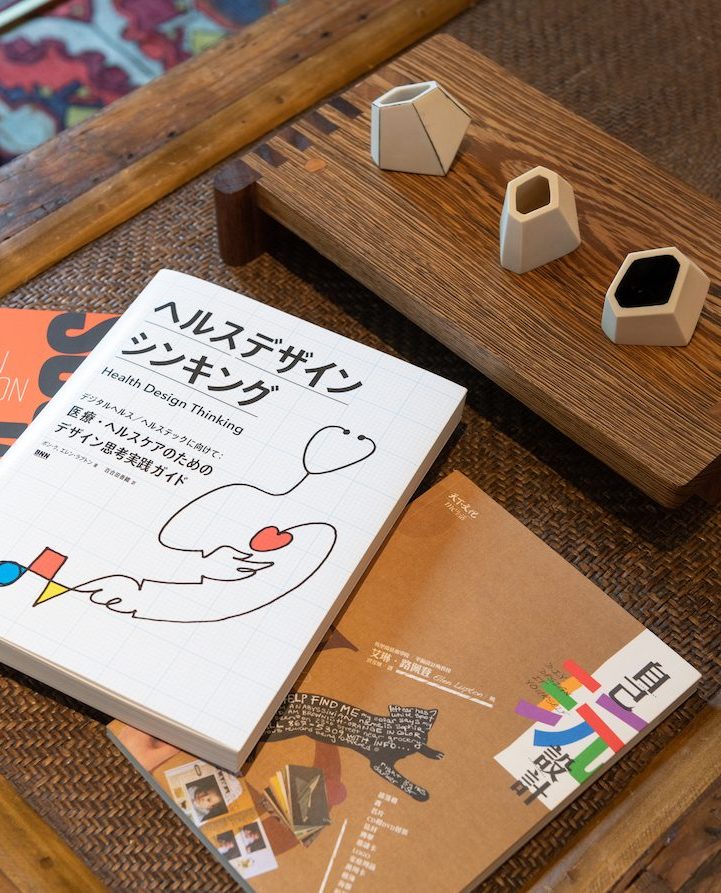

Ellen has published thirty-one books and curated twenty-two exhibitions. Among her favorite book projects are the 2020 Health Design Thinking: Creating Products and Services for Better Health—a “book for people who don’t go to museums,” as she says—and Extra Bold: A Feminist, Inclusive, Anti-racist, Nonbinary Field Guide for Graphic Designers (2021). She designs her books while writing them, editing text and making decisions about the hierarchy between words and images directly in InDesign.

When I asked Ellen what her favorite exhibition was, she responded right away: The Senses: Design Beyond Vision (2018). I remember visiting the show and being amazed at the wide spectrum of design work included. There was the packaging of Compartés Chocolatier, designed by Jonathan Grahm, which Ellen selected for the show to point out how colors, shapes, and forms amplify the sensation of taste and flavor. Another standout was Virginia San Fratello and Ronald Rael’s Cotton Candy Dish—3D-printed objects made of cotton candy.

Daniel Wurtzel’s Feather Fountain was also shown at The Senses exhibition. It is an incredibly delicate and impressive sculpture involving bird feathers that rise up off the mirror base and fly in a central column of air. “Air is thus a crucial component of materials. It hides among the fibers of a felt curtain, and it fills the cells of a foam-rubber mat. Air is also an active, dynamic medium unto itself. Wurtzel is a sculpture artist who works with air,” Ellen wrote in the exhibition catalog.