Alloverstreet reviewed by Michael Farley

Whenever I know I’m going to see a lot of art in a short amount of time, I brace myself in anticipation that I won’t like a lot of it. But on June 20th’s Alloverstreet —a monthly evening of art openings on East Oliver Street— I was shocked by not only the sheer quantity of good work, but by the elusive quality of pieces that felt both resolved and visceral.

Gallery CA’s “Blush” is a group show that’s sparingly hung with an uncommon amount of curatorial restraint. The three artists in the show— Xinyi Cheng, Jeffrey Dell, and Curtis Miller— work very differently, but dialog eloquently (and succinctly) over shared formal concerns. Viewed collectively, the three bodies of work seem to be negotiating the tactile qualities of painting with the graphic quality of the print image; each artist expanding or flattening the perceived depth of field of a given medium’s surface.

Entering the gallery, I immediately fell in love with Cheng’s The Haircut. The oil-on-linen painting positions the viewer looking over the shoulder of a nude man cutting another man’s hair. From a distance, the image has an extremely graphic, illustration-like flatness. The piece still manages to convey a somewhat naturalistic sense of depth, reliant almost solely on subtle variations in Cheng’s acerbic palette. Up-close, the surface is surprisingly nuanced.

Cheng’s mark-making hovers at either end of a spectrum ranging from broad and coarse to fine and delicate, blocking out large chunks of foreground/background and describing individual body hairs, respectively. All of Cheng’s pieces seem intentionally designed to imply an easy translation to silk screen or digital print (the painter has a background in printmaking) but also include so much information that would be lost in translation, such as hints of decision making about color temperature, changes in brush-stroke direction, and ghosts of revisions to the compositions.

Similarly, some of Jeffrey Dell’s abstract screen prints seem to mimic digital renderings. Closer inspection reveals that the familiar gradients and shadows are skillfully produced with manual silkscreening. The effect is underlined by the “imagery” in his work; the compositions are evocative of discarded, misshapen product packaging. Here, the graphic design object is crumpled and warped into the third dimension. The illusion of depth in the prints (a medium so often associated with two-dimensional graphics) works well with the deliberate flatness of the other artists’ oil paintings (a medium typically celebrated for its depth).

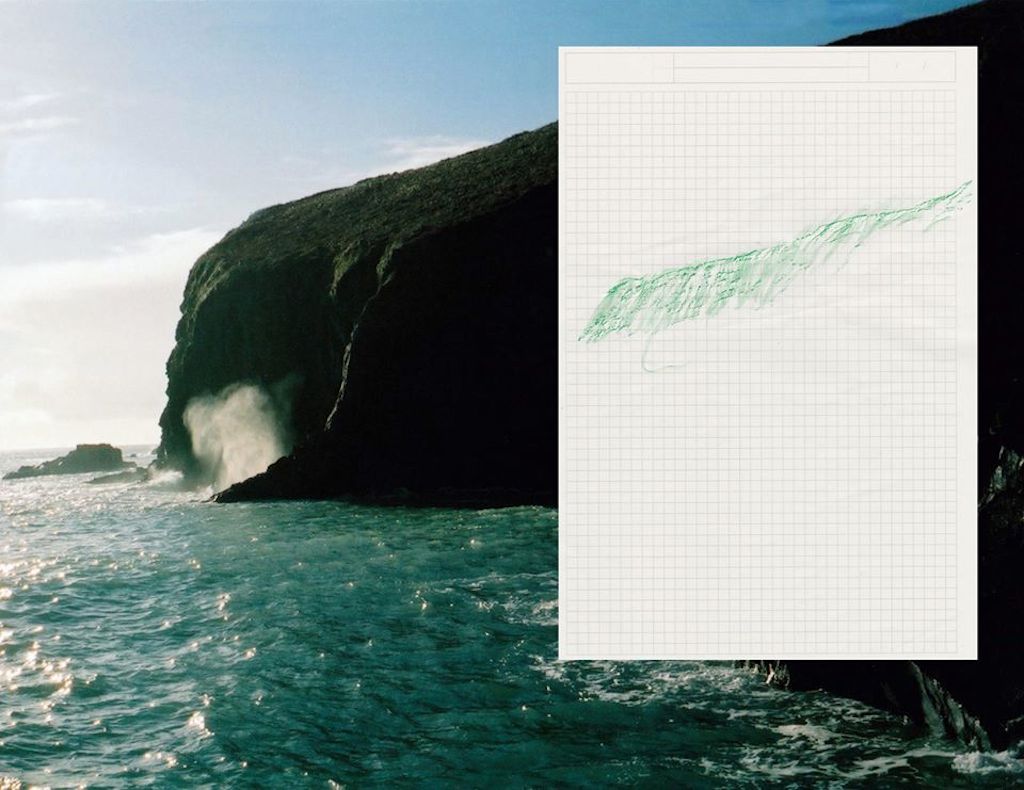

In perfect dialog with these strategies, Curtis Miller’s oil paintings seem to negate their own painterliness. In Waterstroke, the bottom half of the composition is dominated by a pattern of repetitive brushstrokes. In Hollow Panel, abstract expressionist mark-making is obscured by grids or hard-edged outlines. Although a broad variety of techniques are used in their construction, the resulting surfaces feel homogenized. The effect of these design decisions is the inverse of Cheng’s style; whereas Cheng nudges a graphic composition into the realm of painterliness, Miller flattens his paintings into graphics. Miller’s other piece, Untitled no. 7, however, literally oozes three-dimensionality. Beneath a grid of grey boxes evocative of poured concrete, fleshy pink oil paint bleeds into the negative space. I couldn’t help but think of the term “Blush”—a viscous substance betraying vulnerability beneath a membrane—and how apt a title it is for the show. “Flesh” as Willem de Kooning once said, “is the reason oil paint was invented.”

That quote lingered in my mind as I headed around the corner to Isis House in the Copycat, where Sarah Favreau was showing a series of small abstract paintings in varying shades of pink. The small canvases each depict ovoid blobs that reference the body but are unrecognizable as any one specific anatomy. The lack of information in each painting is part of what keeps them intriguing. Each composition could just as easily depict a Silly-Putty stain on a pink pillow or a glimpse of genitalia between two androgynous thighs. Out of all the work in the room, these stuck with me after leaving the gallery. Their scale and the subtlety of the contrast in their palette force the viewer into an intimate position with the work, a surprisingly effective strategy in a room full of “louder” paintings by other artists.

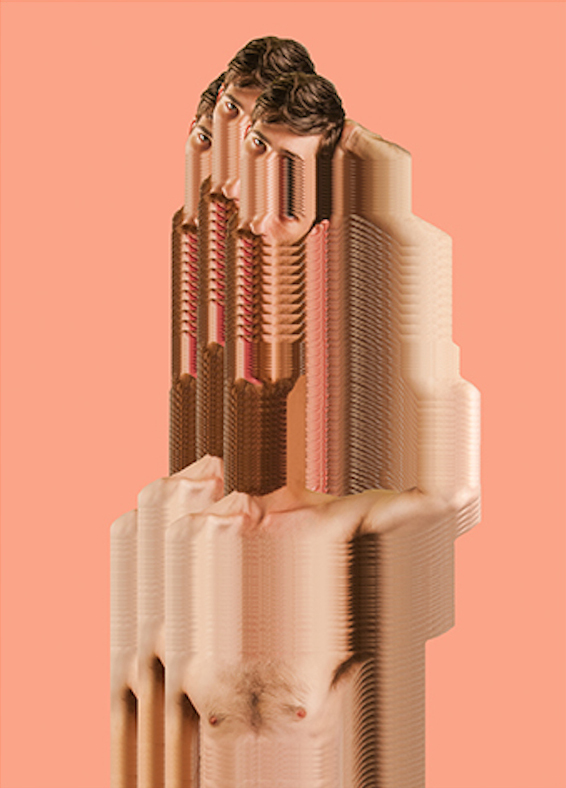

Down the hall, Richard Munaba’s solo show “Peel Me Slow” addresses the notion of intimacy head-on. In one of my favorite pieces in the show, Abstracted Flesh 1, a young man gazes seductively from an poster-scaled digital print. Disturbingly, his head is cloned, with each copy partially obscuring eye contact with the figure behind it. The effect transforms the flirtatious glance into a vaguely sinister invitation being broadcast directionlessly. When the viewer’s eyes are instinctually drawn to search for intent in the young man’s lips, they are confronted with a cascade of data-moshed pixelation. The missing half of the facial expression is elongated into a blur, dead-ending at muscular shoulders and nipples. If Lexie Mountain’s recent, similar prints channel 19th century painting, Munaba’s draws on the unsettlingly strange eroticism of scrambled porn.

Nearby, a model lay naked on the floor, his legs suspended in an apparatus evocative of polio braces. The prosthesis, entitled Let Me Know When You Come, presents the wearer’s anus in a manner that I couldn’t help but think would facilitate the most uncomfortable anal sex (for both parties involved) since lube was invented. “Peel Me Slow” also included some video pieces, that (despite coming across as a bit heavy-handed) added to the overall tension of the show—an inescapable feeling of sexual frustration, obstructed intimacy, and all the angst surrounding issues of surrender/control in relationships. It’s a strong body of work that seems appropriate to its context; while trying not to stare into a stranger’s butthole, I imagined all the countless awkward first homoerotic encounters that have occurred in the hallowed halls of the Copycat Building.

Upstairs, Lil Gallery presented Dave Eassa’s “Dreamhouse,” a solo show that dealt with an entirely different brand of unfulfilled adolescent desire. Eassa draws on childhood memories of his idealized home—a Coca Cola drinking fountain, a basketball court, a pool with a diving board—and realizes them in styrofoam sculptures. I loved the child-like aesthetic and bizarre sense of scale employed in the installation; the diving board towers over visitors and a comically tiny pool, the basketball court takes up half the gallery, but is still too small to be playable.

One of my favorite ironies of the series is that the representation of “luxury” items as fantasy objects are slathered in pricey oil paint, often squeezed straight from the tube like puffy paint. Eassa must’ve spent a small fortune fabricating this work, but I’m glad he did. The impasto application of paint reminded me of the fondant frosting on those cakes that are designed to look like things that people like that aren’t cakes. The kind that they make reality TV shows about. I also thought about the Ghanaian “fantasy coffin” phenomenon, where relatives commission elaborate coffins shaped like whatever unattainable desire the deceased left unfulfilled; a sports car, designer shoe, or favorite food. Maybe it was the lingering fumes with that deliciously earthy smell, but that night I left the Copycat smiling, dreaming of oil paint and a coffin shaped like a tube of Cadmium Red.

ALLOVERSTREET is a monthly night of simultaneous openings and events on East Oliver Street across six arts spaces on East Oliver between Guilford and Greenmount. More info here.

* Author Michael Farley was born at John’s Hokpins Hospital, attended MICA for a BFA in Interdisciplinary Sculptural Studies, and recently received an MFA in Imaging Media and Digital Arts from UMBC. He has a complicated relationship with institutional critique. Although he went to digital art school, he has no website, but did switch to electronic cigarettes.