Michael Farley on Prospect 3 New Orleans – Part 2

Trying to see all of P.3 in one weekend is not a good idea. I get really cranky when I’m sweaty, tired, spending money, and feeling rushed. Once I accepted that I didn’t have to see all of the biennial, and that getting lost in New Orleans was half the fun, I found myself enjoying the individual works more and more. If you visit, stay for a week and only try to see one or two sites that are located near each other in one day.

There’s a creaky streetcar line (absent from the P.3 map) that crawls to City Park from central New Orleans. There are three P.3 sites nearby. The New Orleans Museum of Art is a short walk from the trolley terminus. Here, again, I was asked to pay an admission fee despite the Biennial’s claim that it is “free” and my having an all-inclusive VIP pass (which most people had to pay several hundred dollars for).

The thing about a lot of people who work in the arts (especially in famously hospitable NoLa) is that they’re willing to bend the rules if you’re really nice to them and project apologetic confusion instead of indignation (it’s a strategy that makes even guest-list-obsessed Art Basel Miami Beach week less stressful). Of the three Prospect sites where I was asked to pay admission, I didn’t actually end up paying at any after calmly explaining that it’s customary to let press in for free.

This is one venue, however, that’s worth paying for. In addition to a decent permanent collection, the museum is host to some of my favorite pieces in the biennial. Jeffrey Gibson’s sculptures play with notions of the esoteric in every sense of the word—mashing up the aesthetics of high-brow minimalism with Native American craft to produce artifacts from a hybrid culture, one built from familiar clichés but suggesting inscrutable ritual.

I love looking at these—there are so many layers of materials and processes, each loaded with overlapping associations. In one, an actual mask emerges from a string of black-and-white digital prints of itself. In another, a neon tube light sits in a handmade quiver that looks like translucent animal hide. Humorously, two intricately beaded balls dangle near the base, transforming the odd object into a Dan Flavin erection peeking out from a leathery foreskin.

The minimal wall text accompanying each of Gibson’s pieces is the first I’ve encountered at Prospect that actually adds another layer of appreciation to the work rather than detracting from it. We learn that many of the craft objects were commissioned or appropriated and that the “traditional” looking components are often made with synthetic sinew and acrylic paint. It offers a funny play on notions of “authenticity”—a word used by tourists visiting NoLa with annoying frequency—simultaneously challenging the assumption that the culture of an “other” is somehow more “pure” or “honest” than that of the West, while appropriating the language and materials of minimalist sculpture and modern painting—two genres that strived for those elusive aspirations. Some of my favorite pieces in the show incorporate acrylic paint on felt panels—existing somewhere between Navajo weavings and Bauhaus painting.

In the same gallery, Will Ryman’s “America”—a massive gold log cabin—lurks in the corner like a glitzy pioneer’s unwelcome new condo in an Indian neighborhood he heard had “authenticity.” I really like the narratives the two artists’ work suggest when viewed together. The interior of Ryman’s cabin is constructed from various commodities upon which our national economy has depended—from corn to iPads—all resting on a foundation of shackles. In the context of Gibson’s sculptures, “America” begins to suggest that cultural capital and cultural tourism have become just as important to the success of late capitalist, post-industrial America as the objects in the structure are.

As much as I like this piece, especially in this context, the way it’s displayed is a perfect microcosm of everything wrong with P.3. The sculpture is designed to be entered, according to one sign, but was roped-off with a “Temporarily Closed” sign the whole time I was in the museum. As if to over-compensate (almost comically) for the physical inability to access the piece, it is made more “accessible” by paragraphs of didactic wall text that nearly dwarf the life-size structure. It’s like a foreboding black cloud of patronization barreling down on the little house on the prairie. Really this sculpture speaks for itself and all that’s needed is a materials list, title, and date. But here we get a lengthy explanation of the materials used and what they symbolize, which is evident to literally anyone who looks at the work. Apparently the color gold symbolizes gold. Wow. I never would have cracked that case. Thank you, exhibition designers.

All of the other visitors spent several minutes reading the statement, briefly glanced at the sculpture as if to confirm that what they read was true, and walked away. It’s the exact opposite of what experiencing an artwork should be.

Part of P.3’s didactic tone might be attributed to the problem of addressing race and displaying artwork created by diverse artists using different cultural points of reference (I will discuss more of these artists in my next blog post). Occasionally, overly-dry explanation might seem necessary to avoid far more problematic curatorial issues—sometimes, when considering “otherness,” the art world can seem like giddy 14 year-olds in a suburban basement jerking off to boobs in National Geographic.

Almost worse, identity politics can make cultural production seem like a team sport where one individual must represent (or stand accountable) for whatever group is needed to fill a quota. All of this makes race a tricky talking point—despite the appealing cerebral fertility of “otherness” as an abstraction. Personally, as an individual who was born with pale skin (and a pale penis and balls that I like having) I don’t feel like I should be entitled to contribute much to the discourse over identity. This is frustrating for me because a big part of being a relatively privileged person is wanting to have an opinion on everything.

And so it’s off-putting to me when I see P.3’s Artistic Director Franklin Sirmans include “seeing oneself in the other” as a theme of the biennial. Its off-putting because it seems to imply that seeing oneself in the other is somehow an exception and not what’s expected, like experiencing empathy or sympathy or having something in common with someone different than oneself is an exotic novelty. It’s the art-speak equivalent of starting a sentence with “I’m not racist, but…”

Visiting the New Orleans Museum of Art softened my opposition to that phrase. The biennial includes work by the controversial painters Paul Gaughin and Tarsila do Amaral, nestled amongst the museum’s permanent collection in separate galleries. The wall text here offers an uncommonly nuanced look at their legacies of cultural appropriation and depictions of the Other:

P.3 aspires to take the pulse of the current moment, and to do so in a way that highlights our specific location. But we live in an interconnected world, and we want to hear the world, and to speak out in turn. Gauguin, a French Post-impressionist of Peruvian heritage, “dreamed of returning to a civilization unsullied by industrialization and urban problems” and famously moved to Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands for the last right years of his life. Edgar Degas, his friend and fellow Frenchman, recalls suggesting that he travel to New Orleans if he were looking for an exotic place; but Gauguin decided it was “too civilized. He had to have people around him with flowers on their heads and rings in their noses before he could feel at home.” Gauguin’s honest yet naïve drive to “see oneself in the Other” emits a colonizing gaze, yet perhaps through its pitfalls emerges possibilities for empathy. Posited in a nearby gallery as a counterpoint to Gauguin’s personal search is the work of Brazilian painter Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) instigated the Movimiento Anthropofágico (Cannibalist Movement), who called on the artist-as-cannibal to resist cultural colonization through the affirmation of trans-national and -ethnic influences, positing hybridity not in disjuncture with Brazilian identity, but perhaps as its truest form.

I first assumed “seeing oneself in the other” was an imperative suggestion (a problematic one, at that). Now I see it as a process that is the subject of discussion in and of itself. Perhaps the aim of P.3 is to consider the ways “Otherness” is approached by artists and viewers rather than encouraging audiences to merely see the other.

I mostly can’t get over the irony that contemporary New Orleans is full of people who wear flowers in their hair and rings in their noses— often with little else.

I don’t really mind getting lost looking for the hard-to-find Prospect sites because there’s always something interesting to see in this city. I wandered around bucolic City Park for a good hour or so (unsuccessfully) looking for Will Ryman’s sculpture. Sweaty and exhausted, I tried to buy a smoothie from a street vendor. He looked at me blankly and explained that none of the food vendors or people lounging on the grass were “real”— I had wandered into the set of a Halle Berry movie. Satisfied that I had experienced art, or at least a surreal simulacrum of reality, I set off across the park for the installation at the Delgado Community College.

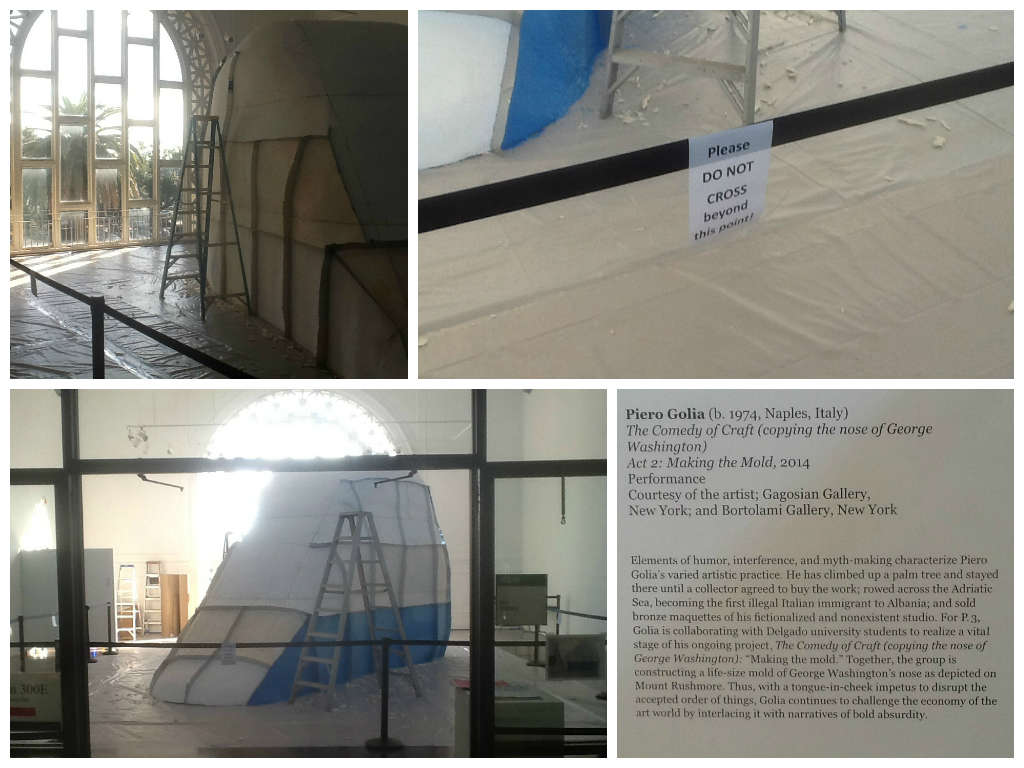

When I climbed to the top floor of the building to see Piero Golia’s piece, I didn’t know whether to be disappointed or laugh. The room is a roped-off studio that houses an amorphous in-progress piece surrounded by drop-cloths and debris. Supposedly, the artist is working with students to re-create George Washington’s nose from Mount Rushmore. Golia’s oeuvre, however, consists of a series of brilliant art-pranks. I can’t help but suspect that here the joke is on the viewer—how many other visitors made a pilgrimage to an out-of-the-way room on I the top floor of an inconspicuous building on the outskirts of the city to look at a mostly-empty room?

Later that night, I told a friend about the experience. He laughed and said Prospect was exactly like visiting the real Mount Rushmore, where he had to pay an unexpected admission fee after climbing a mountain for a pretty underwhelming experience. Maybe this was Golia’s intent? Either way, I actually kind of like the piece/lack of piece. I can’t really complain about the logistics of P.3—most of the work I’ve seen (which I’ll talk about in my next update) has been great, and when approached at a less frenetic pace than we’re used to in the North, the climb is just as rewarding.

Author Michael Farley was born at John’s Hokpins Hospital, attended MICA for a BFA in Interdisciplinary Sculptural Studies, and recently received an MFA in Imaging Media and Digital Arts from UMBC. He has a complicated relationship with institutional critique. Although he went to digital art school, he has no website, but did switch to electronic cigarettes.