The 2016 Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalist Exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Art: A Conversation by Bret McCabe and Cara Ober

Bret: I can’t exactly put my finger on what feels different about taking in the Sondheim finalists this year. Is the assortment of work different or is my headspace different? Though the 2015 Sondheim Finalist Exhibition took place after the Uprising, last year’s finalists were announced before Freddie Gray died due to the injuries he received in police custody.

So this Sondheim Prize process is the first to take place entirely in a post-Uprising Baltimore, and it’s odd how the works included are and aren’t aware of how profoundly Gray’s murder and the Uprising continue to shape and inform Baltimore’s visual art community, in terms of what work artists create, the issues with which the work wrestles, and the questioning of what creative labor should be.

Cara: This year I also observed an emphasis on social justice, politics, and otherness in many of the works presented. There is an overall move toward work that is universal, cultural, and social rather than personal, formalist, or esoteric. Juried shows tend to reflect the trends of the time and are unique to a place, but there are always exceptions, which makes it all more complicated to talk about.

I didn’t expect to see work that directly addresses how Baltimore’s history of racial apartheid creates systemic economic violence; but only a few of the artists’ work included feels critically aware of the contentious political, economic, and cultural upheaval that scars the world in which we live. I’m not saying that all artists have to have a social message or even express political ideas with their work; but when artists casts themselves into the hustle/lottery that is the contemporary art prize application, it is noteworthy that living in Baltimore (or the USA or the world) through 2015 hasn’t prompted a creative worker to leave the confines of their mind and ask something different of their work.

Or maybe a year isn’t enough time for artists to process the changes? Regardless of whether these ideas are explicit, implicit, or purposefully ignored in the work, it’s still there as a subtext, although conversation is uneven.

In general, the Sondheim Prize exhibition always creates strange bedfellows and often results in abrupt juxtapositions between bodies of unrelated works that contradict one another, rather than enrich a visual or conceptual conversation. Although it presents a cross section of some of the regions strongest contemporary artists, it also invites unwanted comparisons and scrutiny to works that aren’t as suited for this particular environment.

This year’s exhibition of Sondheim Finalists at the Baltimore Museum of Art is no exception. Bookending the beginning and end of the exhibit, FORCE and Stephanie Barber arguably have offered some of the strongest and most successful works to come out of Baltimore in the past decade and each delivers a powerful, immersive installation where video and sound coexist seamlessly with sculptural elements. Equally confident is Larry Cook’s glowing room of small sculpture, video, and sound pieces, which explore a politically charged African-American experience.

In between these three powerhouses, the exhibit features works by two documentary filmmakers who have never exhibited in a gallery or museum before, a formalist painter-sculptor whose works are lovely but crammed into a small alcove, and a photographer who explores his Greek heritage in two series of framed photos. This isn’t all bad and all of the works here rise to the challenge of their context, but the crowding and unevenness is, overall, unhelpful to the finalists.

Thinking about the finalist exhibition as a conventional group exhibition is both pointless and inevitable: artists are chosen individually and then corralled into a museum setting. This year offers a strange mix of the safe and adventurous, with a few making fairly conventional documentary work while others explode the notion of what an artist’s work can be. The documentary mode isn’t new to the Sondheim finalists—Gabriel Martinez was a finalist for the prize’s inaugural year in 2006 and in 2007, the first year the exhibition was installed at the BMA, and it included Martinez’s documentary photos from interventionist work (such as using scavenged wood to make benches and installing them at bus stops) and photographer Frank Hallam Day’s Ethiopian beauty salon portraits—but rarely has that work adhered to the commercial journalistic norm.

I’m not one of those insufferable snobs who insists that commercial work—be it journalistic, cinematic, digital/virtual, or even advertising—can’t be art, but what I find invigorating about contemporary artists operating around and within those spheres is how they don’t rely on film language, imagery, tone, etc., found in the commercial norm. Those conventions are the default settings of the status quo, what we see all the time on the many screens that wallpaper daily consciousness.

The way artists hijack, hack, satirize, exploit, and otherwise toy with that status quo is often only found in the niche market of the artist’s web site, gallery, and museum. Yes, new media outlets and channels are doing things and telling stories that legacy media isn’t. But in today’s reactionary hot-take world where confronting issues at-times means bouncing from self-righteous to judgy, a Buzzfeed or a Vice is as much a part of the status quo as The New York Times and the Washington Post.

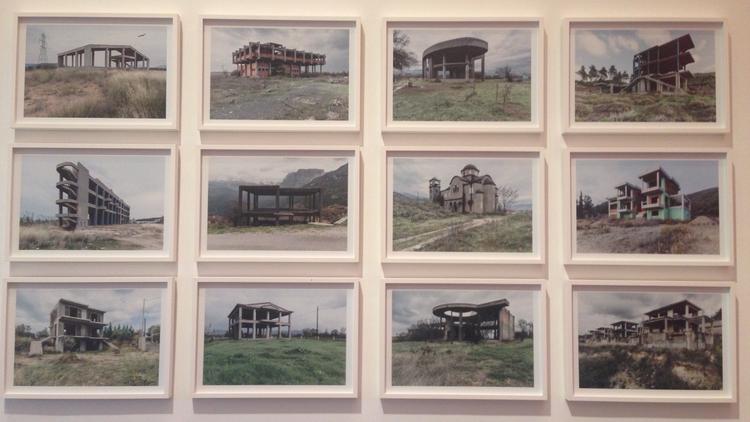

CHRISTOS PALIOS

That indeterminate line separating the journalistic from the artistic—which, in all honesty, may be my hangup alone—is why I feel so underwhelmed by Palios‘ photography. Make no mistake: he makes gorgeous images. There is also a subtle nod to today’s economic upheaval in his subject matter. The 12 photos in his Un-Finished // Contemporary Ruins series feature commercial real-estate buildings in Greece that remain unfinished due to the Greek economic crisis. The latter part of that sentence is a reductively glib way to talk about a complicated set of economic problems and a country wrecked by the financial crisis of 2007-’08, the austerity measures imposed upon it to deal with its debt, and the ongoing efforts to stabilize its economic and political future.

Palios’ photos are an effort to address this economic volatility visually, and it recalls Dutch photographer Patrick van Dam’s Lost in Transaction series from a few years back, which both CNN and the London School of Economics’ blog discussed. The photographic reference here is obvious, and aside from the opportune comparison of unfinished buildings to Greek ruins, what Palios’ visual idea is with this series feels superficial. Unfinished Greek buildings are such a shorthand these days that stock photos exists for such images.

Palios is a young artist with a lot of ideas and excellent craftsmanship, but his two bodies of work presented at the BMA are seemingly unrelated. He’s still figuring out who he is as an artist and this is healthy, but it’s a difficult position to be in because the competition is so tough around him.

I much preferred the lush, enveloping large-format prints from his Conversations series, which depict table tops after family meals eaten in Greece. I enjoy exploring a culture through food and everyday artifacts and these still lives are lovely slices of life, a souvenir for an experience tourists attempt to purchase when they go to Greece but cannot have unless a large family adopts them. I like that these are so ornate and gorgeous, with beautiful fabrics, elegant mismatched glassware, and non-disgusting food remains. I like that they are printed at a table-top size. The narratives are simple, yet consistent, and center around family, cuisine, and tradition. They’re not complicated but they’re meditative and luscious. They’re letting me into a personal experience, to be part of Palios’ extended family.

Yes, those large-format archival pigment prints are more interesting. Meal still lifes have cut a winding course through art history, where food and dining items carry symbolic and cultural value. Contemporary artists such as Mat Collishaw have located more unnerving content in meal portraits, while other artists have explored the social engagements that come with sharing food. Palios’ Conversations do a bit of both. Sunglasses, lighters, wallets, keys, mobile phones, ashtrays, and newspapers rest on the table alongside boxes of desserts, empty tea cups, the remains of peeled fruit, cleaned plates, the residue of shelled nuts, wine glasses, and well-picked fish skeletons.

What we’re looking at is the snapshot of some human interaction, the contemporary ruins of some unfinished exchange that is much more provocative. What did people talk about? What was their relation to each other? Did people leave feeling better or worse? What’s left of the meal won’t answer these questions, but the faint glimpse of this narrative element lends Palios’ Conversation photos a welcome unresolved tension.

THEO ANTHONY

Photographer and filmmaker Anthony suffers from the same quasi-documentary veneer that handicaps Palios’ Un-Finished // Contemporary Ruins series. Once again, the images themselves are visually arresting. That said, most of Anthony’s videos and Chromogenic color prints hew closer to first-person journalism, cherishing its privileged point of view as it observes its subject matter, which here runs from members of law enforcement and media during last year’s Uprising to people at drag races and bodybuilders. Thematically these are fascinating choices—these faces are not the subjects typically found in fine art galleries, much less museums. What’s missing is some organizing idea(s) to Anthony’s POV. There’s a complacency running through these images, as if the mere act of looking at things rarely seen is good enough.

Like Palios, Anthony is also a young artist. In many ways the Sondheim Prize is a proving ground for new talent: for someone who has only exhibited films at festivals, can he make the transition to a museum’s galleries? For someone who is a photojournalist, should he consider the audience and museum environment or should he simply focus on the message? What is the artist’s obligation to audience and to the work, when placing it in a completely new environment where it functions in ways they’ve never had to consider before?

What I think you’re getting at there is the self-satisfaction of claiming to take pictures, not sides: the creation of any image is a choice overstuffed with social, cultural, and political forces, and both the artist’s and journalist’s job involves navigating those choices. For journalism that’s ostensibly valuing the story over the storyteller; in art the possibilities of those choices can be radically considered. And by virtue of the work gathered here it’s not entirely clear what choices Anthony is making when he thinks about what’s taking place in front of his lens.

Take his 12-minute video “Peace in the Absence of War.” It’s made entirely of footage Anthony shot during the Baltimore Uprising between April 27 and May 2, 2015, when the National Guard was stationed around the city and a curfew was in place. Instead of the sensationalistic images that played on loops across cable news during that time—and ever since whenever the subject of Freddie Gray and the officers on trial for his murder re-enters the news cycle—Anthony zeroes in on the people supposedly keeping the peace and the news media personnel when they’re sitting around doing very little, along with long shots of empty city streets at night. They’re scenes of institutional power idling.

When seen last year, this meditative documentary short felt a bit like a glimpse at the systemic infrastructure that keeps white supremacy in place—the threat of and actual force represented by law enforcement and the military, the control over narrative by the media. A year on, and presented with the opportunity to watch the film in a loop in a museum, that impression begins to fade and another one sneaks in: the comfortable access with which Anthony obtains his footage. Watch “Peace in the Absence of War” over and over and over and what emerges isn’t just a peek at white supremacy’s scaffolding but a window into everywhere a white man with camera can travel when a city’s black neighborhoods are occupied. That includes, as evidenced with his “Cop Face” photo series, an ability to get street portraits of police in riot gear.

What does Anthony want to do with this access? Right now he’s satisfied with being able to watch. This reticence reappears in his “Day at the Races (Mechanicsville, MD)” short, another documentary collage. This time Anthony looks at a drag races in southern Maryland. His camera drinks in a couple sitting in the stands, cars at the starting line, young women participating in a Daisy Dukes contest and the men who watch them, and people generally milling about, soaking in the sun, drinking Bud Light. Like in “Peace,” he seems to be interested in people’s everyday boredom. It’s not entirely clear if Anthony is sneering at this culture—his Chromogenic color print “Umbilical Burnout (Mechanicsville, MD),” which captures a guy creating a thick cloud of white smoke from his truck’s spinning wheels, recalls Australian photographer Simon Davidson’s stunning burnout series, and is equally enrapt with the young men who modify their vehicles to do this—but he’s also not making any artistic decisions about the subject matter either.

Not that he has to, mind you—the documentary style of still photography and filmmaking presumes to capture reality as it happens, but that can be an artistic cul-de-sac. Earlier this year at my day job I attended a conference where photographer Jeff Wall talked about his own art and photography’s evolution, and I was taken by one issue he has with the documentary style: that as practiced there’s no collaboration between the people in the picture and the person who takes it. That’s naturally a requirement for journalism; for an artist seeking more from his work, it’s limiting.

That limit is readily apparent in a number of Anthony’s images, especially “A Day at the Races.” There’s a flatness to the footage in the film—the depth of field often looks shallow, as if he’s watching scenes from a safe distance with a long lens, not having to deal with the people he’s looking at on any human level. Anthony, as in “Peace in the Absence of War,” is content just to look.

This passivity wouldn’t feel so insufficient if Anthony didn’t offer something different here. His video “Body Prayer (After ‘The Eighth Elegy’),” featuring footage from a bodybuilder completion, delivers an experience his other work here doesn’t. You get the impression that Anthony is aiming for the kind of singular film/video essay that artists such as the late Chris Marker and Thom Andersen pioneered, and with which places such as the Sensory Ethnography Lab are experimenting. With “Body Prayer” he comes closest to locating a cinematic voice that’s a more visually nuanced and poetic update of the narrative style he uses in his “Chop My Money” short. I’m not sure if the parenthetical in the title is an allusion to Rilke or if any of this footage comes from Anthony’s in-process project with teenage bodybuilder Jake Schellenschlager, but there’s a degree of familiarity and intimacy with everything going on in this film, a closeness to the people and the culture, that’s missing from his other works here.

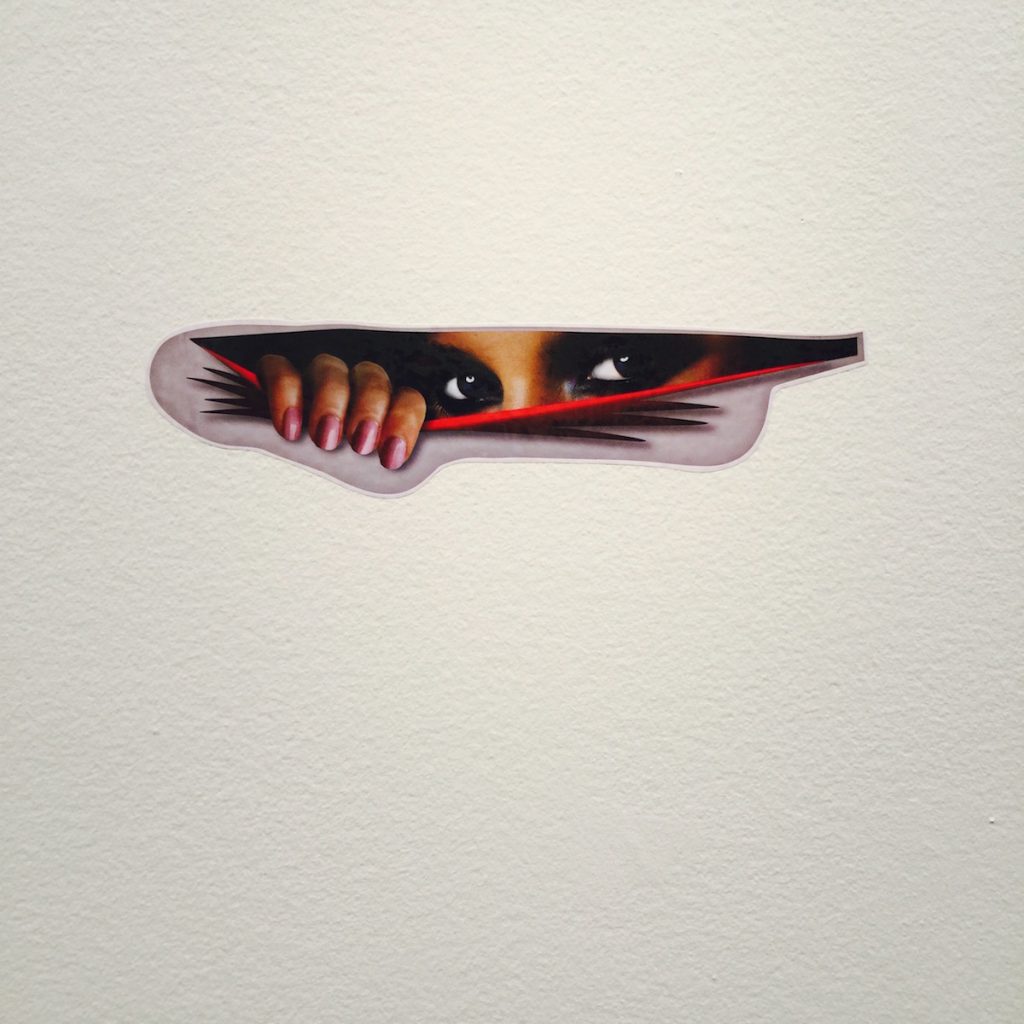

I’m still fascinated and confused by Anthony’s most risky piece—a giant white wall with a bumper sticker fastened in the middle. It’s something you would see on a taxi in the African countries where he’s travelled and depicts fingers spreading open a small window with exotically made-up female eyes peeking out. There’s something weirdly sexy and voyeuristic about it, and my guess is that it ironically embodies Anthony’s feelings about photojournalism and photography in general: the ability to capture and also to deceive or hide. I’m not sure if this piece is an epic fail or his strongest, but it’s the piece that made me stop and scratch my head and wonder, “What the hell is this? What was he thinking?” In contrast, all the other work doggedly tells me what I should think, reinforcing the macho stereotypes he chronicles without challenging them.

ERIC KRUSZEWSKI

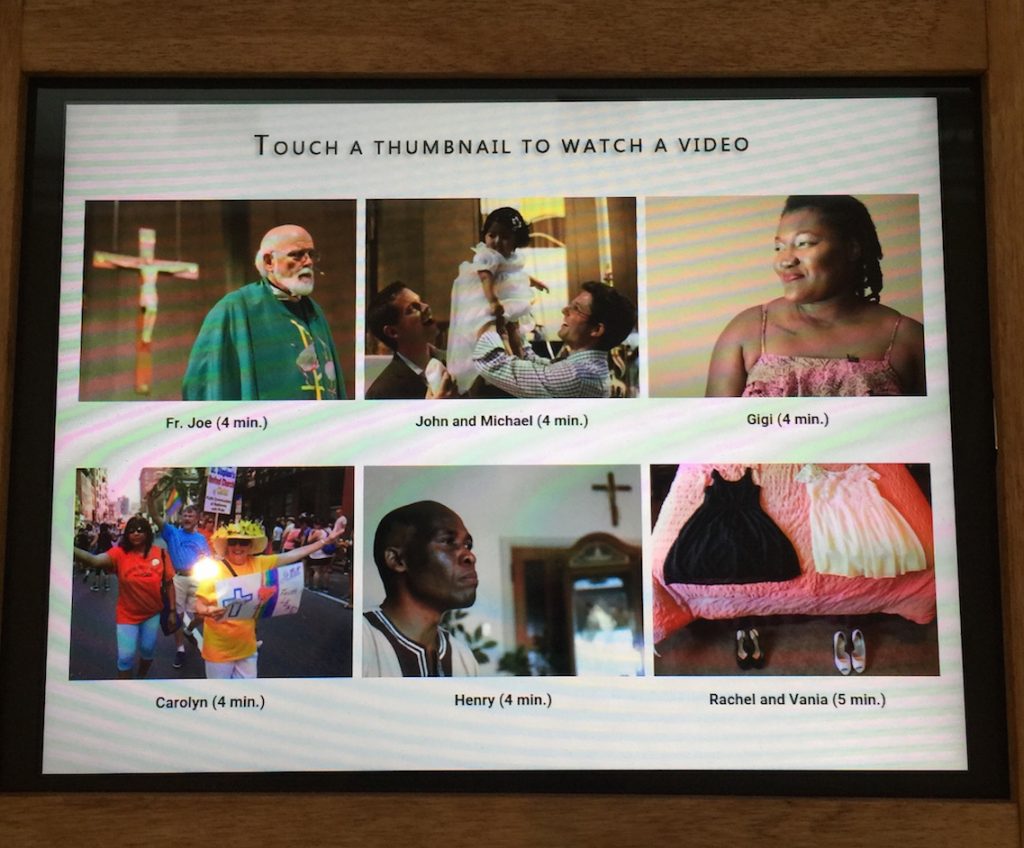

Where Anthony and Palios flirt with the documentary form, Kruszewski embraces it outright. An editorial photographer and videographer for National Geographic, Kruszewsk’s 8-minute “The Lost Flock: Catholic Gays Struggle Between the Church and Self” is a straight-up documentary short about the LGBT LEAD ministry of Baltimore’s St. Matthew Catholic church. The video is projected onto a gallery wall with three pews available to sit and watch. Nearby are a few wooden lecterns with tablets showing supplemental shorts that show more specific people’s stories.

Since this year featured so many filmmakers and videos, I was happy that Kraszewski found an inclusive, clever, and space-specific solution to the problem of showing a film in an art gallery. I believe that film is most powerful when realized cinematically—there’s a reason movie theaters are dark and offer cushy seats. I find it underwhelming nine times out of 10 when videos are played on small screens in a gallery, especially with headphones that always offer the possibility of cooties. Nobody puts the headphones on. For Kraszewski, also a newbie to museums and galleries, to embrace a physical, sculptural, installation approach to his film was transformative. The church pews were a perfect way to activate the space.

The accompanying wooden church-style lecterns with small screens are underwhelming by comparison. Just because this trick worked once, doesn’t mean an artist should use it again. While I understand that Kraszewski has a number of related films to offer, I believe he should have added them into the loop with the main film, rather than offering smaller, distracting options to check out the “extra” work. If the main work is powerful enough, the extra is always just extraneous.

I found the installation to be a site-specific afterthought. The videos shorts are network ready—I only watched about five of the 12 video portraits; they’re all around four minutes long—and “The Lost Flock” itself does a newsmagazine competent job of telling the stories of LGBT Catholics and the relationship with a church that doesn’t welcome them. Any one of these shorts—or all of them as a package—wouldn’t look out of place on a cable/streaming TV outlet or even a film festival.

And as such it’s rather odd to find them here—again, not because I have any issue with commercial documentary work, just that a contemporary art exploration of the documentary mode can be so much more. The installation strategy to present “The Lost Flock”—the pews, the lecterns—feels incidental; the videos work just as well, if not better, when screened on Kruszewski’s web site.

The subject of LGBT Catholics navigating their relationship with a church that still often deems them a moral disorder needs to be told, as do the individual stories of LEAD members presented here. I just kept wanting something more compelling from Kruszewski’s work here than something I could see at any number of options open to conventional documentary storytelling—and again, that complaint could very well be a pretentious hang-up that’s mine and mine alone.

FORCE

FORCE, the collective cofounded by Hannah Brancato and Rebecca Nagle, has offered Baltimore brilliant, sensitive, socially conscious projects for close to a decade and are, in my opinion, among the strongest artists operating in the region. If they win, it will be well deserved and difficult to complain about it. Although their practice has been geared toward public spaces—displaying their proliferating Monument Quilt on the street, in parks, on college campuses, and eventually blanketing the National Mall in Washington—their work absolutely deserves to be seen in a museum, although it should be noted that FORCE is creating additional performances and online programming outside the gallery as well.

For me it’s somewhat odd to see FORCE inside a museum precisely because the collaborative has as little time for the conventional art world as it does for the status quo. Part of the reason why FORCE has been so grassroots effective is due to how its focuses all of its creative labor on its mission: disrupting, dismantling, and deconstructing this world where sexual violence is normalized, victims of sexual assault are blamed for the crimes committed upon them, bodies are treated as heteronormative and cisgender sex objects, and the crime of rape is trivialized, modestly prosecuted (if at all), and otherwise tolerated. That it’s main art project is the collectively made and publically exhibited quilt that Brancato and Nagle have noted is inspired by the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt feeds right into the collective’s name: in physics, force is mass times acceleration, and FOCRE and the Monument Quilt multiplies their power as they gather more survivor stories and speed. And what they’ve created for this exhibition is expectedly potent.

Visually, formally, and conceptually, the Monument Quilt is the powerhouse of this exhibit. It also may be the heart of it. Towering two stories high in the front gallery wall and projecting so much red that the accompanying walls glow pink, the Monument Quilt successfully changed its context to dominate, yet also entrance, visitors to the museum. From a distance, it beckons. Then, when you come in for a closer look, the multitude of personal, heartfelt details draw you in deeper, both from a visual standpoint and a conceptual/emotional one.

Video testimonials and interviews further personalize the piece and are seamlessly embedded. One does not question the video screens’ presence; they are another way to engage with the quilt’s diverse voices and they function like another quilt square. Thankfully, the sound is audible a few feet away, so no headphones are required.

Overwhelmingly, this carefully curated selection of items comes together to show that rape is not just a women’s issue, that it’s part of larger social justice issues this country is battling. The impact on the viewer is empowering and inclusive. When you finally pull yourself away from it, you feel connected to a larger movement. Installation as a two-story-high wall, rather than the usual iteration as a floor piece, reinforces its power.

And it’s a testament to how confidently Brancato and Nagle have shown that creative work is activist work. Every FORCE project, from their culture jamming Pink Loves Consent and the Playboy Guide to Consent campaigns to the menagerie of activities that accompany Quilt displays, the message, the art-making, the organizing, and the community building are all part of the endeavor. FORCE isn’t merely making art that has an impact. FORCE is all-in dedicated to envisioning a different world, one where consent is the norm and sexual violence isn’t.

DARCIE BOOK

Are they paintings or sculpture? How does paint function like cloth over an armature? I love that Book is able to combine elements of high fashion and historical costume with painting and sculpture. Her use of dried sheets of paint, ostensibly carefully scraped off of a non-binding surface is innovative and manages to harness the viscous, sexy, luscious qualities of paint, but also surprises us by using paint as a three-dimensional building block.

I was disappointed that these works were crowded into what appears to be a hastily built alcove, an attempt to buy them space and white walls, while crowded into the same room as Palios and FORCE. This is the only space where three artists with completely disparate works are crammed together and this contrast doesn’t hurt the Monument Quilt, but does diminish the other two. Less is more when it comes to curation; Book’s slick and clever works, many as small as a sandwich, could have stood up, at least formally, to the giant red quilt and offered an interesting visual conversation in the gallery had there been just two finalists there.

Book is also the lone artist here operating in almost purely abstract concerns. This is work that doesn’t make sense anywhere else but in a gallery. Her 11 pieces—latex paint on birch or combined with vinyl and other media— are intimate, thoughtful, and dedicated to establishing her own visual language. The biggest problem for me isn’t the more modest scale; it’s that I feel Book is still in the figuring-out process with her vocabulary. Flitting somewhere between the latex sculptural work of Lynda Benglis and the abstract density of Jack Whitten, Book’s work has one foot in painterly sculpture and the other in sculptural painting, and hasn’t yet established its own idiosyncratic stride.

Within the context of so much socially conscious work, Book’s abstract pieces are an anomaly. It’s not clear how they relate to a larger Baltimore conversation or what the juror’s criteria was for choosing the finalists this year. Maybe they just thought the works were visually strong and deserved to be there? Within this context they are lovely sore thumbs, and they’re hard to stay focused on with so much social commentary competition.

For me the latex, gold leaf, and vinyl installation “Jasper” stands out not only because its scale rises to the gallery’s expanse but because Book also liberates the work from the wall. Hanging pieces such as “Venetian Red Fan Form” and “Io” pin her three-dimensional thinking to a two-dimension display case, never quite allowing her efforts to exploit paint’s viscosity as anything more than a surface. They feel like online digital abstractions fabricated for seeing IRL and little more. In space the suppleness of her visual thinking has more room to breathe, and the billowy, fabric-like textures she can achieve with latex and vinyl opens up more decadent, disorienting possibilities.

LARRY COOK

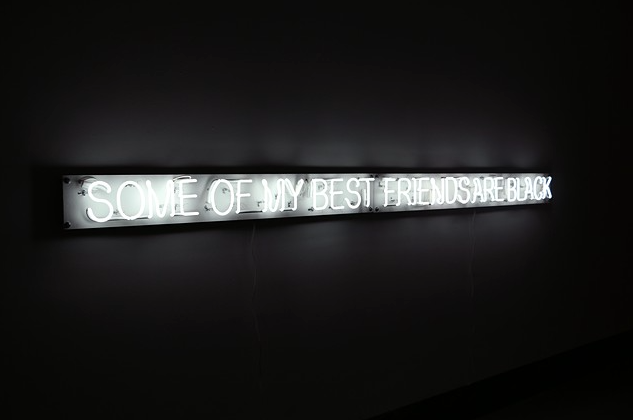

Larry Cook is a conceptual artist who explores, deeply and broadly, the meaning of being black in America today. He’s got a whole darkened room to himself here, which is great for his two-channel video and neon pieces. It comes off as a confident, understated, and well-curated solo exhibit where small wall works are given an exorbitant amount of space and a viewer can linger over details and absorb them at a leisurely pace.

Although his 2013 Sondheim Finalist entry included original photographs, this exhibit includes a number of small constructions that combine appropriated images, sound, and text into reflections of American culture. His large projected two-channel video, “Stockholm Syndrome,” features footage of slaves from the TV mini-series Roots and the movie 12 Years a Slave on the left and video footage of the crowds assembled for Barack Obama’s 2008 Presidential acceptance speech. Louder than the other works but consistent in message, the video is an indictment of America: despite electing our first black president, the very real legacy of slavery haunts us. The title indicates the artist’s opinion that black and brown people are suffering from the same psychosis that kidnapping victims develop: an alliance and empathy with the captors. In his neon text work “Some of My Best Friends Are Black” and smaller mirrored boxes, Cook reflects white America back onto itself, showing how it looks from a black perspective.

Cook’s work here isn’t merely an order of magnitude stronger than what he displayed in the 2013 Sondheim exhibition, it’s a savvy, pointed response to indicting white supremacy that communicates at the page-skim pace of the meme or the tweetstorm. “Stockholm Syndrome” needs less than two-minutes to drive a historical comparison into the uncomfortable, while “Some of My Best Friends Are Black,” spread across a gallery wall all by itself, to allows its neon medium to do its incisive, satirical heavy lifting.

Neon signs are the typical media for bail bondsmen, unhealthy carryout and food delivery joints, pawn shops, check cashing and cash advance places, liquor stores, tax preparers, and other businesses concentrated in majority black, economically disinvested communities. Cook’s uses this media to spell out the insulting “some of my best friends are black” apologia-qua-defense white people use to deflect their racist thinking exquisitely and immediately connects an individual’s rationalizations of whiteness to the institutional racism that undergirds America. This piece throws a hand grenade at white people who “check their privilege”: acknowledging that you’re aware that the pedestal atop which you stand is built on the extracted capital and traumatized bodies of black people doesn’t recuse the ignorant shit that comes out of your mouth after you’ve pointed that out.

Although Cook’s political views and righteous anger are palpable in this work, his restraint in communicating abstractly, deftly pitting popular culture against itself through familiar trophes makes his message hit its target, rather than bounce off. Humor, mystery, subtlety, and irony all work together here, and works pollinate and inform one another successfully, so that a (presumably) white museum audience, as well as POC, will connect with this work. Cook has proven himself to be a powerful and sophisticated practitioner. His message matches his medium and, in my opinion, he would be well deserving of a Sondheim win.

I don’t know how much “righteous anger” the pieces here contain, as Cook achieves his ideas with the calm composure of a somebody who recognizes the facts of America for what they are. Both “Stockholm Syndrome” and “Some of My Best Friends Are Black” are showcase pieces, but Cook’s most devastating work is the almost affectless “The Making of Identity.”

It is little more than a mirror you can look into when you put on the accompanying headphones, which play a loop from Roots when Kunta Kinte is whipped into accepting that his slave name is Toby. The loop is only a little more than two-minutes long, and it only takes a few seconds of that time to feel instantly the crushing historical echoes reverberating in a white man asking an abducted African, “What’s your name?” As you stand there looking at yourself listening, other scenes flash through the brain’s movie screen—for me, it was the legendary tale of Muhammad Ali asking Eddie Terrell “What’s my name?” in the ring, three words that have become the title to numerous hip-hop songs—and Cook’s work slyly provides this aural reflection of how America was built.

STEPHANIE BARBER

Like Cook, Stephanie Barber is a second-time Sondheim finalist. Since her 2011 BMA exhibit in which she converted her section of the gallery into a collaborative studio, Barber has distinguished herself as a conceptual filmmaker, with screenings at the Whitney Museum, MOMA, the Tate and others, but has also developed as a writer, poet, and sculptor.

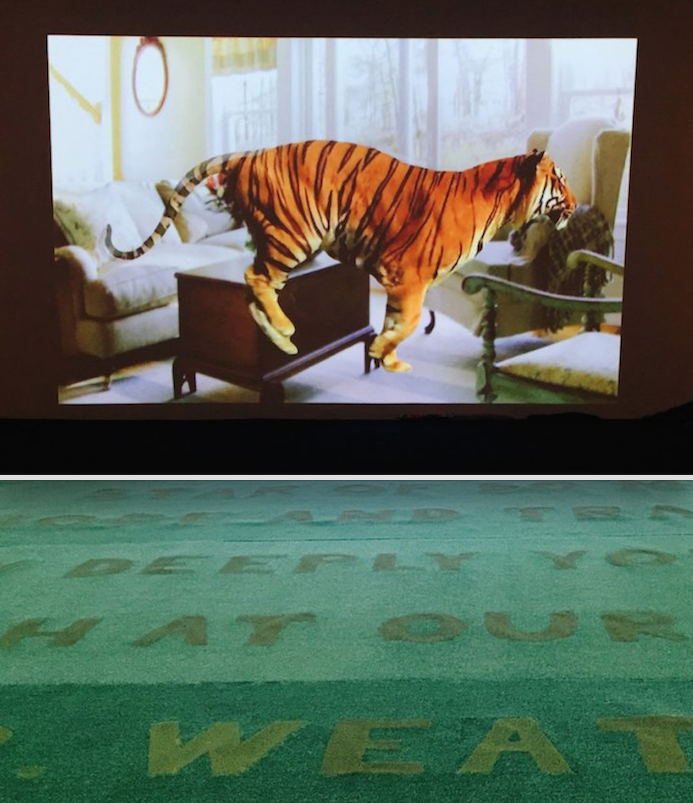

In the large, back gallery, Barber screens a silent video that depicts a tiger loping through various domestic environments, positioned above a “Lawn Poem” where text is fashioned from cut pieces of artificial turf. An ongoing project, Barber’s lawn poems have been installed outside in other environments and feature meticulously cut sections of sod, embedded into a flat grassy field, where the two colors of grass contrast and eventually grow together over time as the poem disappears. I mention these past works because, taken as a group, they are a testament to the artist’s commitment to her ideas and their output: poetic, ephemeral, labor intensive, and perfectly executed.

After looking at and reading Barber’s work for nearly a decade I have to confess that when I encounter it now all I’m confronted with is the overwhelming emotional complexity she’s aiming for with every aspect of her creative practice. She takes huge swings with her art—as in, what-is-the-individual’s-place-in-the-universe big ideas typically associated in America with men such as Herman Melville, Richard Serra, and Walt Whitman—and does so with an ambitious vocabulary of formal adventurousness inside the cozy, personal media of experimental film, poetry, and performance. And, like Cook, she returns to the Sondheim with some of the most sublimely conceived work of her formidable career.

Everything here—the “Tiger Transportation” video installation, the “Lawn Poem” and “Mounds of Snakes” installations, the “3 Essays on Nature” viewfinder and slidecards pieces—revolves around the themes outlined in “Sentences about Nature as a Metaphor for Economic, Emotional and Existential Horror” piece, which is a gumball machine that dispenses the essay for 25 cents per sentence. I had no change on me the first time I visited the exhibition; I returned a second and third time with pocketsful of quarters ready to buy whatever was left but ended up each time only buying a dollar’s worth, simply because I didn’t want to hog this experience for myself.

There’s a doubly savage wit to this text-delivery model. She’s basically getting people to pay her 25 cents per sentence for her writing, which is sadly not too far off the market rate for some web sites, magazines, and papers. Given the text’s psychological themes, she’s also getting people to seek advice as casually as they buy gum, frustratingly the only way a majority of American can afford mental health advice. Some of the ones I purchased were sentence that flirted with fortune-cookie wisdom: “what is the miracle of belief that coaxes the river downstream.” Others conveyed a humanistic positivity familiar to the mindfulness slash wellness industry: “simply looking at photographs of nature improves mental functions like concentration, joy, and comprehension.” And others landed with the crippling weight of an Emil Cioran aphorism: “wild through and through and still so sad.”

A similar range of enigmatically affecting sentiments appears in the viewfinders, which pair found photos with text. Each viewfinder slidecard delivers an essay—titles: “animals as decoration, totem,” “natural world, interior design,” and “captivity, fear, transcendence”—that lodges under the brain’s skin with a disarmingly passionate ease. Again, putting this kind of heavy writing and thinking in an artifact some of us best recall as a childhood toy, makes her nature meditations feel monumentally personal while wryly commenting on the dismissively juvenile way far too many people treat issues such as climate change.

As a conceptual artist, Barber is focused merging linguistics and poetic uses of language with visual, non-verbal qualities. It’s heady, but there’s also a subtle, oddball humor that softens and humbles her work. In this exhibit, you are encouraged to walk on the artificial grass (“Please do not touch the snakes” reads the wall text) and the vintage viewfinders for the audience members to click through and a 25-cent gumball machine were you can purchase “an idea” encased in a plastic bubble are deceptively compelling.

Filling a whole gallery with a variety of media—video, floor sculpture, and tactile elements—Barber proves herself to be adept to connecting with a museum space and audience, while maintaining complete consistence and balance. Her message is opaque and vaguely explores civilization’s interpretations of nature, but this gallery so beautiful and leaves room to luxuriate and explore. If Barber wins this, it’s well deserved.

The “Lawn Poem” here just kills me. Yes, she’s revisiting an idea and piece she created with real grass in Wisconsin in 2009 (check out her “For a Lawn Poem” chapbook essay about the idea). And I think she made early prototypes for that in artificial turf, but to see the lawn poem in fake grass in the context of “Nature as a Metaphor for Economic, Emotional and Existential Horror” is crushing. This fake environment is a nature diorama mirror of real, contemporary life. The poem reads:

“Oh wily nature

Star of so much

Hope and tragedy

How deeply you must

Blush at our flimsy

Armor. Weathermen.

Love, insurance. Clocks

And small settees.”

The text moves at the seemingly confounding logic of Barber’s films and writing, where she intentionally short circuits the smoothness of colloquial speech to highlight how insufficient language is to communicate what goes on in our hearts and minds. And the “Love, insurance. Clocks” line here is simply breathtaking—in three words Barber captures everything beautiful and tragic about being alive: love, the folly of human efforts to protect ourselves from the inevitable chaos that life brings (insurance), and the horrifying reminder that it, this life, is fleetingly and frustratingly finite.

The winner of the 2016 Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize will be announced Saturday, July 9, at 7 p.m. at the Baltimore Museum of Art. The exhibition runs through July 31, 2016.

Author Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.

Author Cara Ober is Founding Editor at BmoreArt.