L.A. to New York, to Washington: The Dwan Gallery at the National Gallery by Kerr Houston

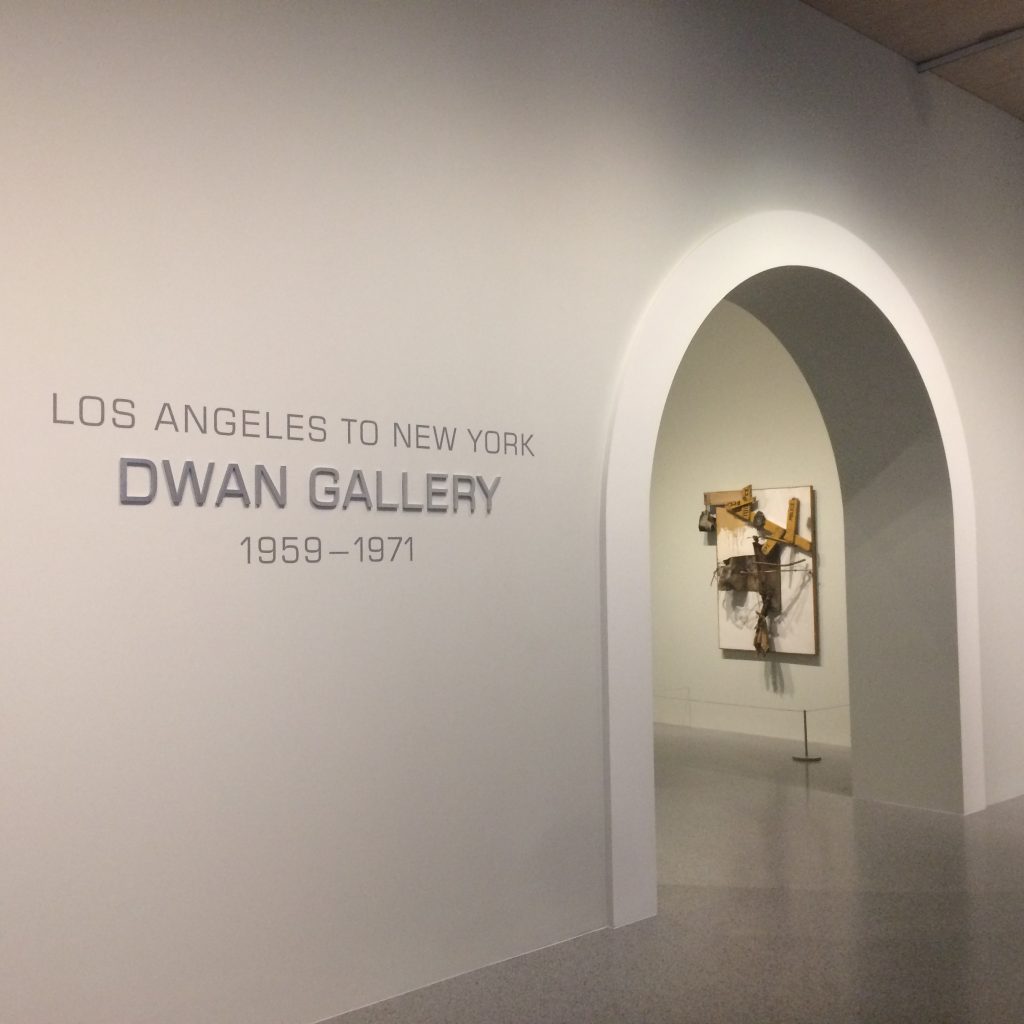

In one of the last rooms of the National Gallery’s impressive Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery 1959-1971, a monitor plays a brief film shot by the gallerist Virginia Dwan during a 1969 trip to Mexico with Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson, whose work she showed and promoted.

Taken from a boat gliding along a river, the film is an exercise in greens and browns: a palette that left a deep impression on Dwan (“I was in a sort of intoxication of green,” she later recalled). Suddenly, though, Smithson ordered the pilot to halt; debarking, he and Holt surged ahead and began to make one of his celebrated mirror displacement pieces. At once impressed and nonplussed by Smithson’s determination, Dwan tried to follow – only to find herself stuck in quicksand. She called for help, but her friends didn’t look back.

“Plunging forward,” she later recalled, “I was able to extricate myself and stagger on after them.” And yet, having walked through this intelligent show, we realize that Dwan could never in fact fully extricate herself, in a larger and more abstract sense. From the quicksand, yes – but from the making of contemporary art, no: for by that point, she was deeply imbricated, immersed in the unfolding history of art.

It was a history, after all, that she had played an active role in shaping. Born in 1931, Dwan was a granddaughter of one of the founders of 3M, and she inherited a considerable fortune at a young age. After moving to Los Angeles, she married in 1958, and her husband encouraged her to pursue her dream of opening a gallery – which she did, a year later.

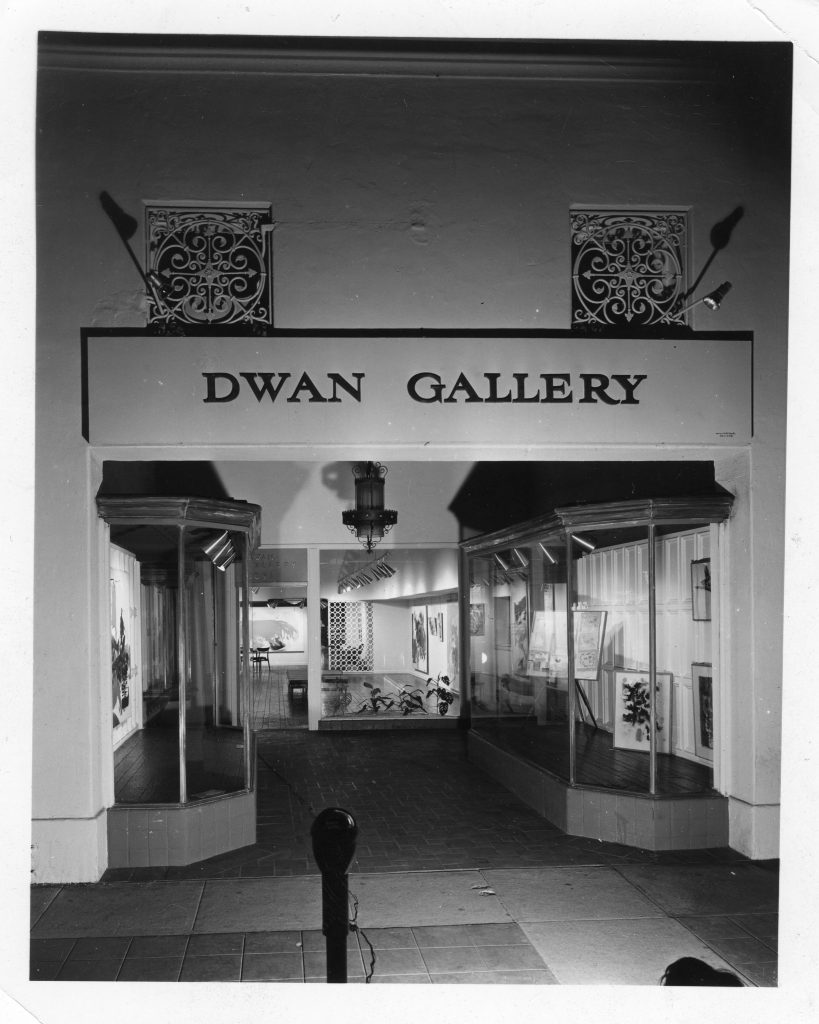

The Dwan Gallery, initially based in a former men’s clothing store in Westwood, first opened its doors in 1959 and soon became an important player in the nascent Los Angeles contemporary art scene. Within six years, Dwan opened a second gallery in New York City, and although she eventually closed both galleries in 1971, they had by that point already hosted a remarkable 134 shows. Those shows, moreover, included a simply astonishing range of works, from Andy Warhol’s perplexing Brillo Boxes to the jittery sculptures of Yves Tanguy, and from the coolly cerebral installations of Robert Morris to Robert Smithson’s film of his monumental Spiral Jetty.

Many of these works are now, of course, canonical, and indeed much of the art in this show will be familiar to anyone with an interest in modern and contemporary art. After all, the 1960s are perhaps the most studied period in the history of art, and in fact James Meyer, the curator of the current show and the author of an engaging essay in the hefty accompanying catalog, is one of the leading active scholars in the field, known for his insightful analyses of Minimalism.

But how, then, can we re-see these objects, from a fresh perspective? In short, this show proposes that we can can do that by embracing an institutional angle of analysis: by thinking closely about one of the galleries in which such work was seen and about its evolving interests and tendencies – and, ultimately, about its influence.

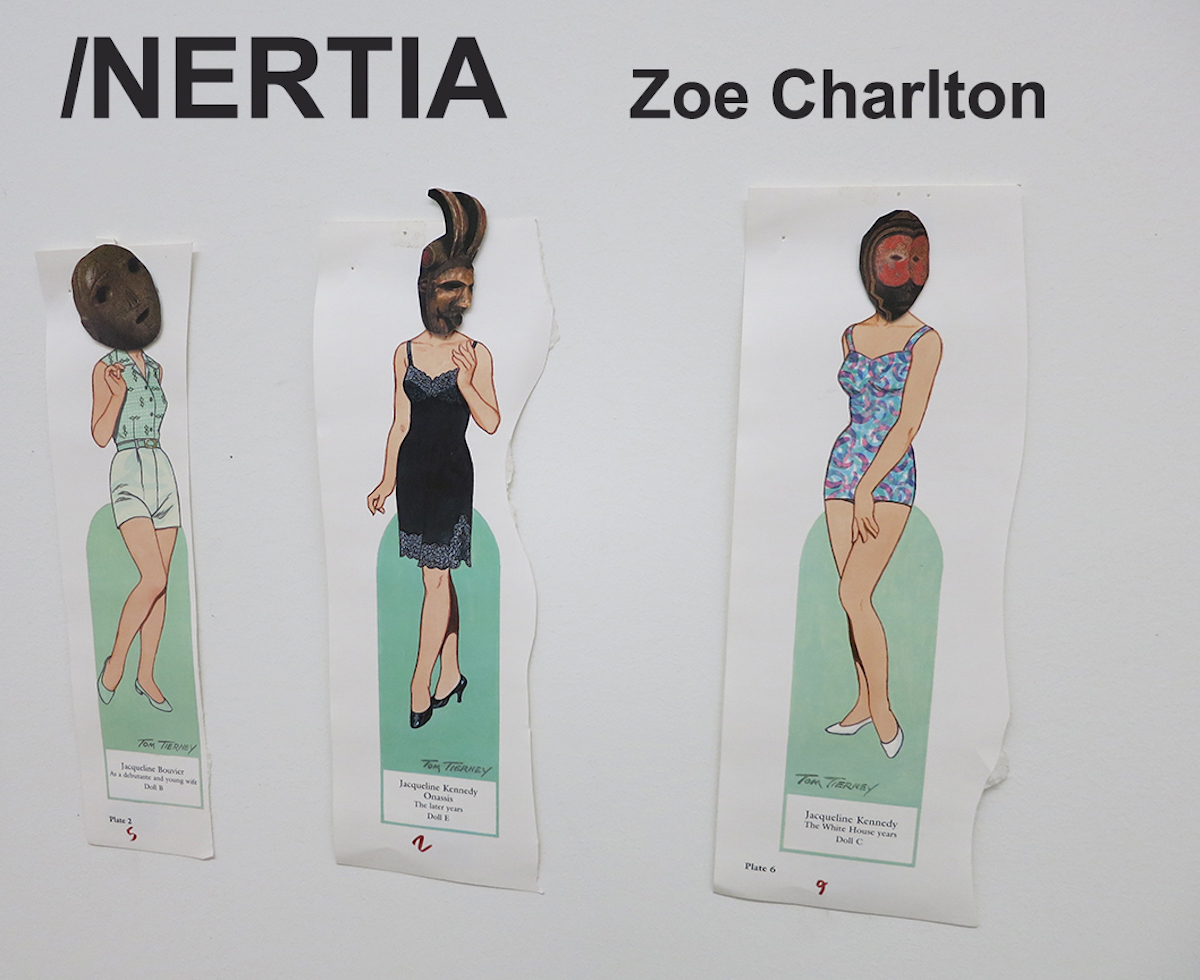

Exterior of the first Dwan Gallery, Broxton Avenue, Westwood, Los Angeles, 1961

Exterior of the first Dwan Gallery, Broxton Avenue, Westwood, Los Angeles, 1961

Photographer unidentified, Courtesy Dwan Gallery Archives

That’s an approach that has acquired, it’s worth pointing out, considerable momentum in the last few years, as historians of both art and exhibition design have begun to study the institutions that shaped the development of contemporary art in increasingly nuanced terms. Recent books by Kristina Wilson and Amy Newman, for instance, have offered satisfyingly fine-grained analyses of the ways in which MoMA and Artforum influenced the perception and reception of contemporary art at particular historical moments.

At the same time, there has also been a serious attempt to excavate the creative work that took place in Los Angeles in the mid-1900s: a milieu traditionally marginalized in histories that position New York as the sine qua non of high American modernism. In a 2009 book, Kristine McKenna explored the importance of the L.A.-based Ferus Gallery, and in 2011-2 Pacific Standard Time, a series of coordinated exhibitions and programs scattered throughout greater Los Angeles, offered an unprecedentedly detailed look at Californian modernism.

The Dwan Gallery, it’s clear, was a major element in that landscape. Indeed, as Irving Blum, who managed the Ferus Gallery for a time, once observed, Dwan was “the gallery that was the most competition.” Nevertheless, the contributions of Dwan and her two galleries have remained largely overlooked: until now, that is. In 2013, Dwan – who is now in her mid-eighties – promised 250 works from her collection to the National Gallery. This show was motivated largely by that gift, and it effectively demonstrates the scope and depth of both Dwan’s bequest, and her contributions to the arts.

Without a doubt, it is an ambitious exhibition. Unfolding across a dozen rooms, it’s installed on the lowest floor of the museum’s newly re-opened East Wing (which, by the way, has emerged from its recent renovation looking rejuvenated: the re-installation of Richard Serra’s Five Plates, Two Poles, for example, prompts us to perceive its rugged mass anew).

Meyer and his curatorial assistant Paige Rozanski have assembled 125 objects, drawn from a variety of public and private collections, including Dwan’s behest; in addition to works of art, we see occasional pieces of correspondence between Dwan and some of the artists with whom she worked. But even that is not all, for the show is accompanied by a short film about Dwan and a second, smaller exhibition of archival items connected to her galleries – wonderfully evocative price lists, log books, and letters – in a nearby study center. Dwan’s galleries may have been long overlooked, then, but their time has apparently arrived.

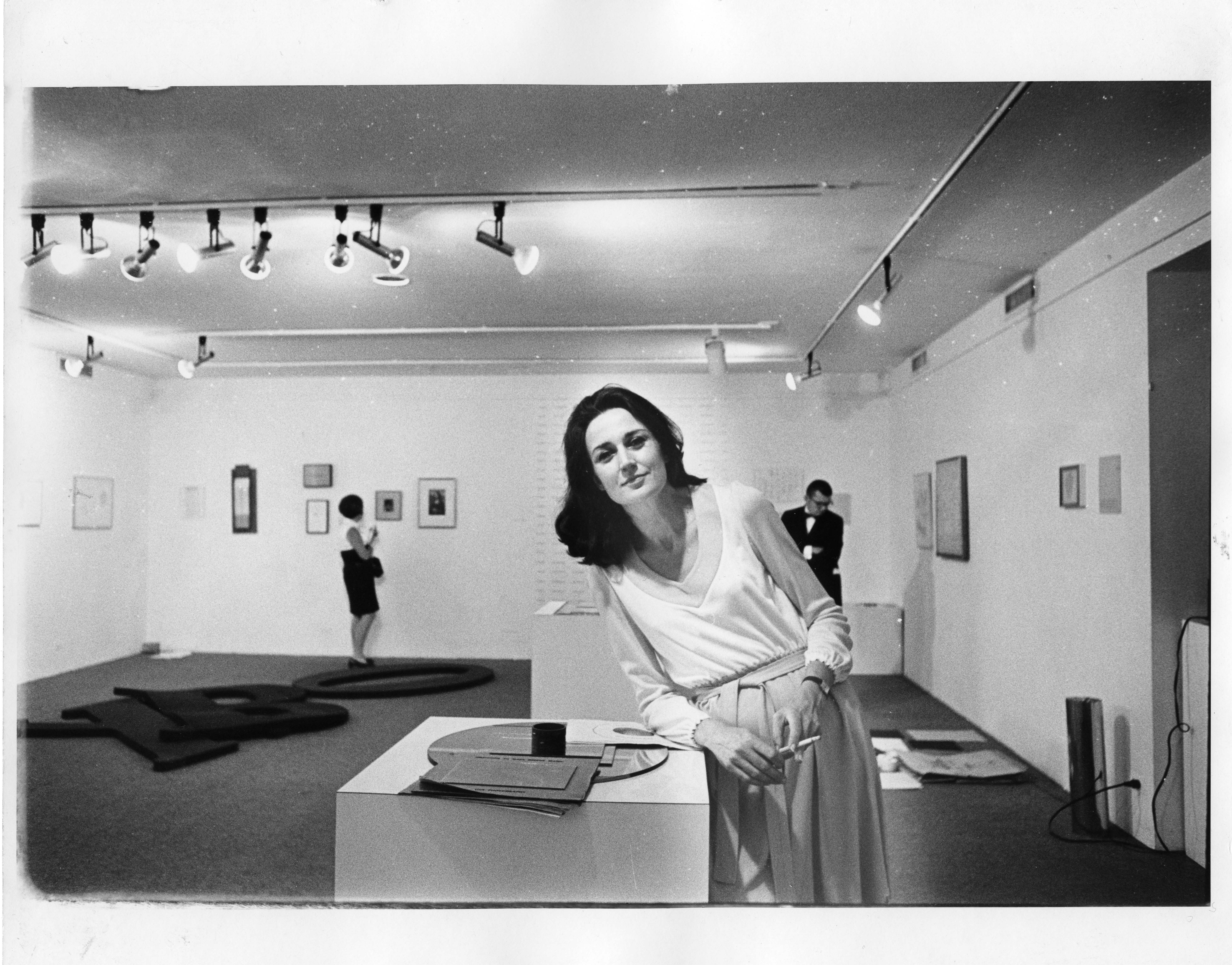

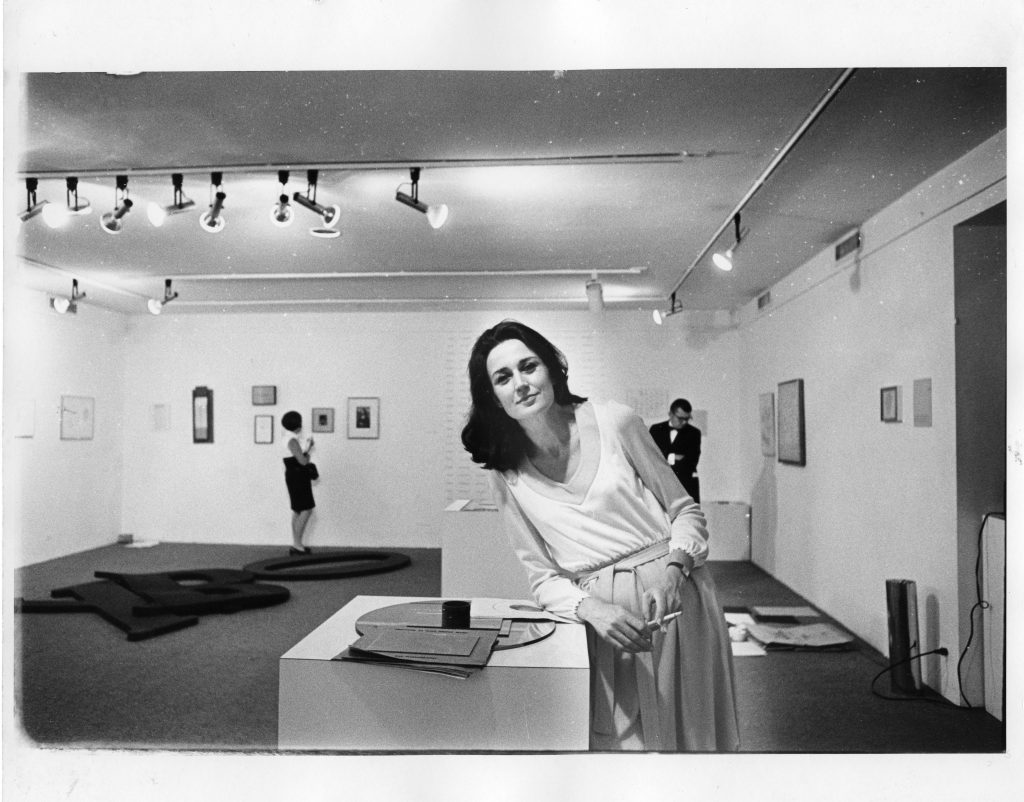

Virginia Dwan in her gallery during the exhibition Language III, Dwan Gallery, New York, May 1969, Photo: Roger Prigent, Courtesy Dwan Gallery Archive

Virginia Dwan in her gallery during the exhibition Language III, Dwan Gallery, New York, May 1969, Photo: Roger Prigent, Courtesy Dwan Gallery Archive

So what, exactly, did Dwan show over the course of thirteen years? The first room of the show is largely given over to a handful of Abstract Expressionist paintings: bold, gestural work by Philip Guston and Franz Kline. Given her relative youth and inexperience, Dwan initially drew up agreements with several New York galleries, and seems to have been temporarily content to show works that embodied the by-then familiar “10th Street style.” Interestingly, though, Meyer positions Dwan’s interest in AbEx as elegiac, rather than simply conventional. Kline died in 1962, and Dwan’s decision to show his work in 1963 can thus be read as a gesture of farewell to an acclaimed artist – but also to a movement, which was quickly being eclipsed by a range of other exciting experiments.

Those experiments quickly attracted Dwan’s open-minded attention, and the first room of the gallery also features a muscular combine by Robert Rauschenberg and a black painting by Ad Reinhardt, which Dwan exhibited in successive 1962 shows. More than half a century later, one can still sense the raw excitement of iconoclasm and possibility implicit in the two works. Reinhardt’s painting anticipates, in its sober restraint, the intellectual exercises of Minimalism. Rauschenberg, on the other hand, gamely extends the ideas of Duchamp in suspending shards of a police barricade, a baroque reliquary containing a tooth, and an oily cloth against a barely marked canvas. Operating, as he claimed, in the gap between art and life, Rauschenberg re-imagined the canvas as something other than the arena in which the Abstract Expressionists had claimed to do heroic battle: the surface is now a flatbed, the site of provisional juxtaposition and contingent wrack.

The directions charted by the gallery quickly multiplied. The November 1962 show “My Country ’Tis of Thee” featured works by Warhol, Oldenburg, and Lichtenstein, among others – a month before MoMA devoted a symposium to the subject of Pop Art, and a full three years before Barbara Rose would attempt to analyze the emergent style in an essay entitled “ABC Art.” Indeed, the Dwan Gallery’s developing ability to identify new tendencies and willingness to enthusiastically support its artists sometimes helped to incubate pioneering work.

In 1963, the gallery solicited work involving boxes from a number of artists, including Warhol, who wrote back wondering if he might submit copies of the crates in which Brillo pads were shipped. That was fine by the Dwan Gallery, and the show of archival materials includes a letter from John Weber, the gallery manager, in which he informs Warhol that “Your idea of using cardboard boxes is sensational.” True enough: for those boxes, three of which are included in the current show, soon became seminal examples of Pop Art and prompted a series of remarkable meditations by the philosopher Arthur Danto.

Andy Warhol Brillo Box, c.1964 house paint and silkscreen ink on plywood each unit: 33.34 × 40.64 × 29.21 cm (13 1/8 × 16 × 11 1/2 in.) © 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Jerry L. Thompson

Andy Warhol Brillo Box, c.1964 house paint and silkscreen ink on plywood each unit: 33.34 × 40.64 × 29.21 cm (13 1/8 × 16 × 11 1/2 in.) © 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Jerry L. Thompson

At around the same time, Dwan was also developing relationships with European artists. She gave Yves Klein his first American show, and in 1963 invited the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely to L.A. in advance of an exhibition of his work. The result is one of the highpoints of the current show, as Tinguely’s almost manic interest in motion and dynamism resulted in a series of comical adventures and winning works. Driving around L.A. with Dwan in search of motors for his kinetic sculptures, he apparently gravitated towards especially large models; when Dwan wondered about their scale, Tinguely excitedly responded, “That’s just it. It’s the motor that counts.”

Such a conviction is also evident in a maquette version of Tinguely’s exhibition announcement, which endearingly informed readers that “The opening is from 6 RPM to 8 RPM.” And it’s apparent, as well, in the exhibited examples of his kinetic sculpture, delightfully haphazard arrangements which almost tremble with energy. (They are now to fragile to run continuously, but an accompanying video shows one of them in motion).

Tinguely’s assemblages can feel almost childish, though, when viewed in relation to the work in the next few rooms of the show. Edward Kienholz’s Back Seat Dodge ’38, for instance, offers a contrastingly dark and dystopic vision of motorized technology: in the mutated hull of a modified car, we see a sloppy act of drunken sexual activity that seems to verge on violence. Is this a rape? A merely awkward encounter? It’s hard to say – but it was certainly enough to offend visitors to the Dwan Gallery, to which a vice squad was promptly summoned, in order to investigate charges of immorality. Dwan, though, remained undeterred, promptly rewarding Kienholz with the first show at the newly opened New York branch of her gallery, in 1965.

Edward Kienholz Back Seat Dodge ’38, 1964 paint, fiberglass and flock, 1938 Dodge, recorded music and player, chicken wire, beer bottles, artificial grass, and cast plaster figures overall: 167.64 × 304.8 × 396.24 cm (66 × 120 × 156 in.) overall installed: 304.8 × 368.3 cm (120 × 145 in.) Copyright Kienholz. Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.. Digital Image © [year] Museum Associates / LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NY

Edward Kienholz Back Seat Dodge ’38, 1964 paint, fiberglass and flock, 1938 Dodge, recorded music and player, chicken wire, beer bottles, artificial grass, and cast plaster figures overall: 167.64 × 304.8 × 396.24 cm (66 × 120 × 156 in.) overall installed: 304.8 × 368.3 cm (120 × 145 in.) Copyright Kienholz. Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.. Digital Image © [year] Museum Associates / LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NY

Over the next few years, Dwan’s galleries continued to feature challenging, progressive art. Works by Jo Baer and Agnes Martin tested the possibilities of painting; Sol LeWitt moved towards an increasingly conceptual practice; Shusaku Arakawa exhorted the viewer to steal his drawings, if possible (a challenge then taken up by several art students, in what might fairly be seen as an early experiment in both institutional critique and relational aesthetics).

One of my favorite works in this section of the show, though, is Robert Morris’ beguilingly simple Card File, in which he carefully classified and catalogued each of the activities that had led to its completion (there are entries, for example, for Conception, Materials, and Signature). An early iteration of the Sixties interest in positioning the artist as a laborer, the file combines language, system, and archive in a seamless manner, while paradoxically unifying process and product.

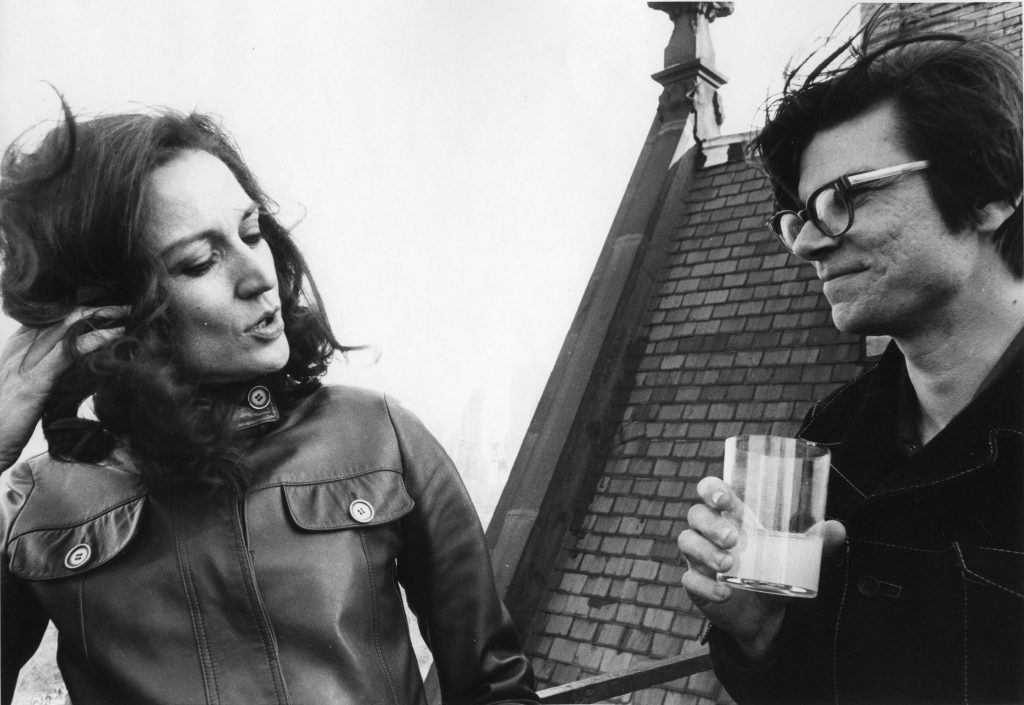

Morris’ work, then, is intellectually tidy: a sort of elegant koan. By the late Sixties, however, Dwan was increasingly drawn to the ambitious land art of Smithson, Walter de Maria, and others, and she both underwrote several of their projects and showed related sketches and installations in her galleries. The last few rooms of the show are given over to this period, and for several reasons they strike me as the only real weak spot.

There is, of course, the basic challenge involved in trying to show works that are fundamentally devoted to escaping, or exceeding, the gallery: by design, these are works that cannot be exhibited. Meyer tries, gamely, to give us a sense of their effect by using a series of large wall photographs, but the effect is distracting and diffuse; reproductions simply can’t substitute for the real thing. And then, too, there is a curiously distended focus on Smithson, who is treated in almost hagiographic terms here. Granted, he enjoyed a close friendship with Dwan, but the inclusion of one of his videos, fifteen of his drawings, and one of his writings threatens to throw this otherwise neatly paced show off balance.

When we finally reach the last room, which features two paintings by Robert Ryman and alludes to Dwan’s decision to shutter her galleries in 1971, the effect is weirdly anticlimactic. Ryman’s thoughtful work can hardly compete with the prolonged ode to Smithson – who nearly eclipses Dwan as the central focus of the show.

Virginia Dwan and Robert Smithson, New York, 1969 Photo: Roger Prigent Courtesy Virginia Dwan Archive

Virginia Dwan and Robert Smithson, New York, 1969 Photo: Roger Prigent Courtesy Virginia Dwan Archive

Otherwise, however, this is an elegantly conceived exhibition that is characterized by several thoughtfully conceived transitions and trajectories. We’re led from the early Rauschenberg combine, for instance, into the second room by means of a maquette that the same artist designed for a 1962 show.

Kienholz’ theatrical tableau is preceded by several glancing references, in the wall text, to the artist’s collaborations with some of Dwan’s artists; initially a marginal figure, Kienholz then takes center stage in the mid-1960s. Throughout the show, too, there is a discernible evolution in both the materials used and the scale of the works: paintings and modestly sized sculptures yield to a variety of forms and formats that eventually outstrip the gallery entirely, spilling out into the open spaces of the American West.

One of the implicit arguments of the show, then, is that the West embodied, for both Dwan and many of her artists, a sense of unfettered possibility. (“I wanted to feel,” said Oldenburg, after visiting L.A., “the West.”). But Meyer also points out that artists were not the only ones making the trip to California. Indeed, he suggests that the Dwan Gallery can be seen as part of a larger system of networks – he cites the interstate highway system, created in 1956, and jet travel – that facilitated bi-coastal communication.

Certainly, one could argue for an even more expansive notion of networks; increasingly inexpensive color photographs and a wave of ambitious young graduate students writing for Artforum also played a vital role in the dissemination and theorization of contemporary art. But there’s no need to quibble, really, as this show clearly demonstrates the historical importance of the Dwan Galleries in an artistic landscape that was becoming truly global for the first time.

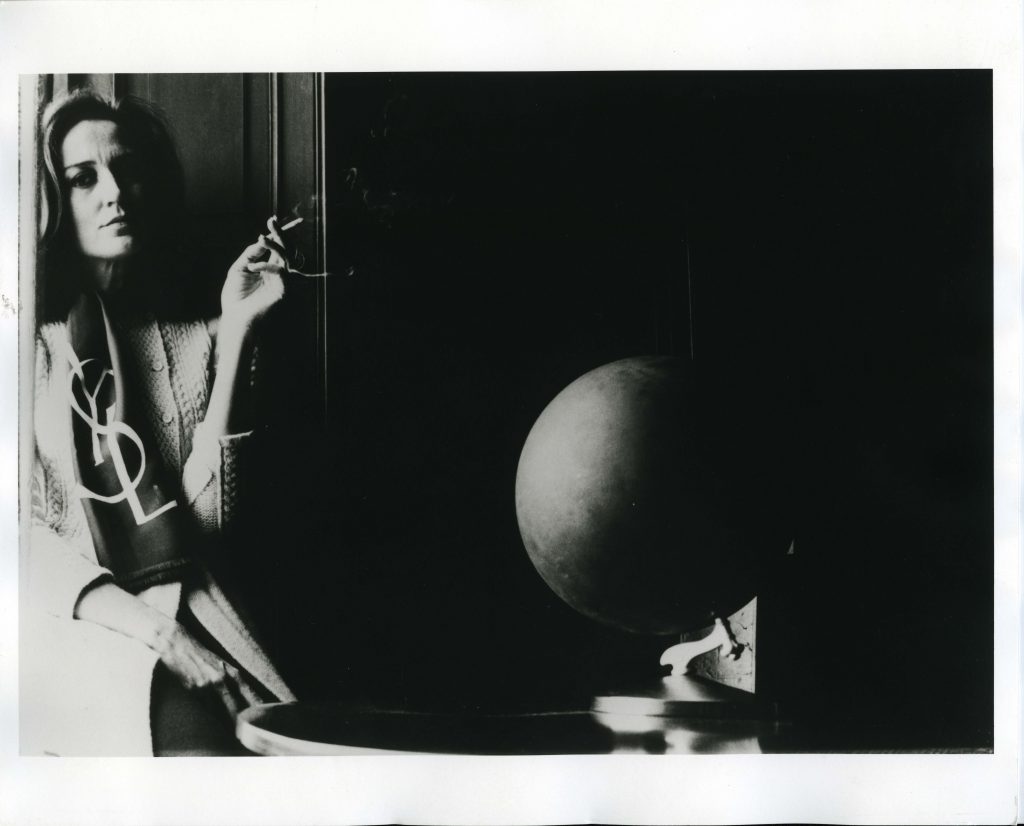

Virginia Dwan at home in New York, 1969 Photo: Roger Prigent Courtesy Virginia Dwan Archive

Virginia Dwan at home in New York, 1969 Photo: Roger Prigent Courtesy Virginia Dwan Archive

Given all of this, it is rather shocking to realize that Dwan’s galleries operated in the red for every single year of their existence. They were never, in bluntly economic terms, profitable. That said, one can hardly conclude, after seeing this show, that they were therefore not successful, or productive. When Sol LeWitt learned that Dwan planned to close her galleries, he quickly wrote her a plaintive note that almost refused to accept the news. “It has played so important a part of my life,” he told her, “that it is difficult to get accustomed to the idea that it will not exist.”

It wouldn’t; the Los Angeles branch had closed in 1967, and the New York gallery followed suit on June 26, 1971. And yet, in another sense LeWitt was arguably correct – for, as this show indicates, the consequences of Dwan’s decision to open and maintain a gallery are still very much with us.

*******

Author Kerr Houston has taught art history and art criticism at MICA since 2002. He is the author of the book An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2012), and his recent writings range from an article on a metaphorical aspect of the Sistine Chapel chancel screen, in Source, to an extended essay on Candice Breitz’s Extra, in Nka.

Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959-1971 will be on exhibit at the National Gallery of Art through January 31, 2017