Angela N. Carroll on Malcolm Peacock’s The Museum of Trayvon Martin: A Meeting Before Labor at Terrault Gallery

“You wonder if you aren’t simply a phantom in other people’s minds. Say, a figure in a nightmare which the sleeper tries with all his strength to destroy. It’s when you feel like this that, out of resentment you begin to bump people back. And, let me confess, you feel that way most of the time. You ache with the need to convince yourself that you do exist in the real world that you’re a part of all the sound and anguish, and you strike out with your fists, you curse and you swear to make them recognize you. And alas, its seldom successful.” – Ralph Ellison from Invisible Man

When I first learned about the exhibition, The Museum of Trayvon Martin, I feared the worst. All too often, brutalized black bodies become props, their lives and bodies become visible only by proxy, only because of the violence inflicted upon them. We are inundated with video replays of those violences, footage of those murders, and blaring rapid gunfire aimed at unarmed children and men. We observe and are triggered by this redundant carnage, disturbed and disparaged by the barrage of queries digging up the victims’ history in search of criminality. I have become hyper aware of these exploitative trends, painfully astute to the alternative facts.

Malcolm Peacock’s three-part installation at Terrault Contemporary and a separate location on Calvert Street provided a critical and moving analysis of Trayvon Martin’s life, not just a recant of his murder at the hands of George Zimmerman.

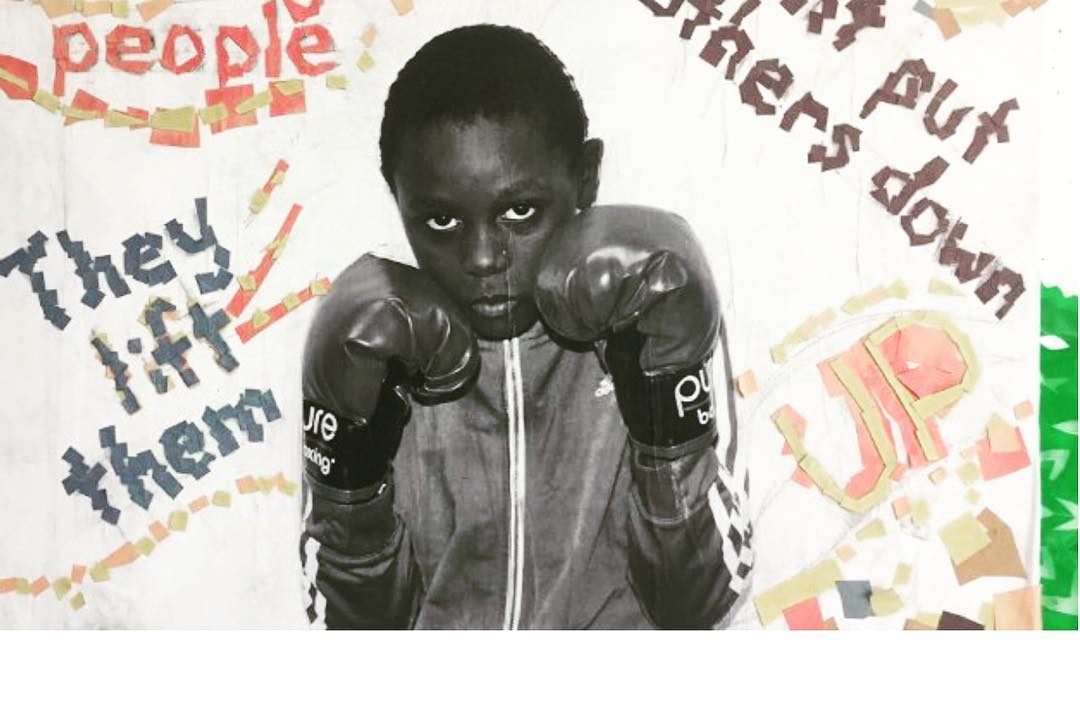

The great success of Peacock’s “museum” is its determined and persistent visualization of Trayvon not as a victim, but as a teenager. His life, his joys with family and hobbies are highlighted and remembered. Peacock’s exhibition stressed the importance of not just looking, but seeing Trayvon, and acknowledging that his life is reflected in all of our lives. Peacock considered him a brother, because he could be his brother, and is in many ways a little brother, nephew, or cousin to us all.

Part I: “The Waiting Room”

One could easily walk past the installation in Part I, never noticing the slight curatorial decisions Peacock employed. A waiting room is decorated with balloons, a table full of magazines and CD’s. The wall is checkered with a collection of black women’s images, mostly celebrities, torn from black publications.

One balloon reads, “Congratulations!” The next, “It’s A Man!” The balloons are tied to the arm of a couch. Nike baby booties lay on the seat of the couch. A tiny toddlers backpack lay on the floor beside the couch attached to the balloons. We are celebrating the arrival of a child, a black boy whose body will be read as that of a man. Because of the reading, the safety of his body will never be secured.

The installation is a quiet nod to America’s fear of black masculinity. A study conducted by the American Psychological Association found that because black children are consistently perceived as older, their bodies are targeted in ways that their white peers never encounter.

“With the average age overestimation for black boys exceeding four-and-a-half years, in some cases, black children may be viewed as adults when they are just 13 years old.” The APA further contextualizes this claim by stating, “The evidence shows that perceptions of the essential nature of children can be affected by race, and for black children, this can mean they lose the protection afforded by assumed childhood innocence well before they become adults.”

Part II: “The 7-11”

The small gallery space is transformed into a 7-11, complete with red orange and green wall trim, and a fully stocked snack rack with chips, skittles and beverages. Visitors are greeted at the entrance to the space by a small girl and an older woman. Before they are granted admission the small girl must ask, “Are you black?” The response will grant one entrance to Part II and Part III or halt admittance until the non-black visitor is accompanied by someone that openly identifies as “black.”

The initial press release and all advertising for the event specified that “A Non-Black individual who would like to attend the show must arrive and be present with a Black person when entering Terrault.” I spoke with several white patrons who expressed their initial angst and concern over this request. One woman revealed that when the announcement was made nearly two weeks before the show opened, she struggled considering whether to reach out to the black people she knew for fear they would think she was “just using them.”

I witnessed a few nonblack people come in and immediately walk back out at the request. Others walked in and asked random people they assumed were black if they would accompany them to Part II. At least one white male patron affirmed “Yes” when asked the prompt and was admitted with no hesitation. I later learned that disdain for the prompt encouraged many others to skip the exhibition all together.

I stood against a wall observing many of these interactions, and it was incredibly clarifying. The forced racialization, and reflection on privilege/accessibility to space is a crucial aspect of not only Martin’s murder, but most instances of unwarranted violence against black bodies.

The presumption of access that allows some bodies entry and marks other bodies violent or disruptive; a menace in those spaces, calls into consideration the systemic nuances of race relations, and more specifically, the profiling and surveillance of black bodies.

It also creates a challenging requirement that forces people who do not identify themselves as “black” to literally feel within their own bodies a frustration/angst/subjectivity experienced everyday by people of color forced to endure the micro-aggressions and legislatively sanctioned invasions against their bodies.

I thought a lot about the words scholar/author Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote to his son in Between the World and Me when he stated, “You are growing into consciousness, and my wish for you is that you feel no need to constrict yourself to make other people comfortable.”

I thought it apt and an intelligent curatorial rule to restrict access to the exhibition by constricting ones self-reflexive lens to racial identifications. This prompt could be an exhibition within itself, a critical examination of identity constructions, privilege and the body in public space.

Once inside Part II, visitors are surrounded by the familiar archetypes of a convenience store, but also by pedestals with placards that narrate the ways Trayvon may have engaged with the objects. The items that were selected to represent Trayvon declared his humanity valid and solidified that he was just a normal kid. Photographs of Trayvon with his family, a hair brush, model airplanes and the tools Martin used to construct them, grillz, a football helmet, a hoodie, a Community Volunteer of the Year award, all provided a new youthful and innocent representation of Trayvon.

Even the snack rack installed at the center of the space was weighted; printed cost estimations paralleling Trayvon’s life with the market value of the snacks were stuck to each row. One note read “$ The cost of having to give your best friend the sound of rustling grass over the phone as a gift .00”. Another read, “$ The cost of your little brother waking up in the middle of the night and not knowing when you will be home .00”.

A smaller room within the 7-11 installation was more disturbing, reflecting items and documentation from the last hours of Martin’s life. A small LCD looped surveillance camera footage from the 7-11 Martin visited before he walked home. The video shows Trayvon purchasing iced tea and skittles. Then the footage abruptly cuts to a man taming an alligator. This jarring cut is a heavy historical trigger.

In the Jim Crow era South, hunters, zoo keepers, and average joe’s had been known to use black babies as bait to lure alligators out of hiding. Peacock posits Trayvon as a similar kind of sacrifice, a dangling babe set before the inhumane gaze of an itchy-trigger-fingered white supremacist. His life was devalued and devoured before it could mature. The 7-11 surveillance footage is the last time anyone other than Zimmerman saw Trayvon Martin alive.

Part III: “Lost in Screens”

You are given walking instructions to find a previously unspecified location where Part III is installed and a ticket. It is dark outside but the walk from Saratoga to Calvert is well lit. I could not help but worry about the safety of other black, male bodies walking to the next site alone through an area whose residents could mistake them, as Zimmerman mistook Martin, for criminals.

Had Peacock considered the implications of this walk? Would black men or boys walking alone be safe? Were black people directed to walk with non-blacks so that they would be less likely to be stopped by the police while walking to the second installation?

I wondered what Trayvon felt walking home, hooded to protect himself from the cold rain. After about 20 minutes or so of walking, I made it to the second site. I felt numb. I had arrived at a home; Trayvon was not so lucky.

The older woman and small girl greeted us at the bottom of a long and narrow stairwell. They collected the tickets and then directed us up the stairs into a studio apartment. The room was sparsely furnished; a mattress and a monitor were placed in the center. At least twenty bodies packed themselves around the monitors’ pale blue glow. “My brother made me conscious of my body. Made me touch my being and lay in it.”

“Lost in Screens,” the 14 minute short film installed at Part III, was the first time I was able to really see Peacock’s perspective, a painful rumination about his kindred connection to the vulnerability of Martin’s body, and his thoughts about his own mortality. “I may be bad, but I will not yell. When I was 17, I found out that I had another brother. I learned his name after he died. Mama said he came into this world screaming and that he left doing the same.”

Most of the film is silent. Contemplative text from Peacock scrolls white on a black screen narrating his thoughts about Trayvon. “All I knew what that he was killed in the rain. Followed and then killed in the rain.” The silent film is cut with the sound of a chainsaw and brief commentary taken from Peacock’s mother and Ms. Terry Williams, the mother of contemporary artist Theresa Chromati, about what it means to be the mother of black children, and discuss the hazards and pride of black identity.

“To me its another black child killed senselessly,” said Peacock’s mother. “Totally senseless killing. Some things you just can’t take, especially with Trayvon being so close to my own son’s age. I blocked myself out from that. I just, didn’t want to hear it.”

“When you know what Black means to you, you can take that and shake things up,” said Ms. Williams. “I have control to make it however I want. There is power in that.”

“I am their son? I am their sun. I am. I am their son.”

At the film’s conclusion, Peacock invites viewers to enter a closet. “My brother rests in our closet. If you would like to see him, please enter his space quietly. Leave space for him to breathe.”

A thin curtain separates the two spaces. The closet is small and brightly lit. Pictures imagining Trayvon’s potential future are pasted at eye level on the closet walls; wedding photos, images of Trayvon as an adult, as a father of children. Man-size Nikes sit on the top shelf of the closet. Most visitors were stone faced until this part. Something about witnessing a future that will never come to fruition moved many to tears. Heavy reflections.

I sat for a long time in the darkness of the installation watching people see Peacock’s words and then take in the sadness of the closet. The Museum of Trayvon Martin was a deeply experiential assessment of the humanity and validity of black lives.

**********

Author Angela N. Carroll uses illustration, citizen journalism, documentary film, words, and experimental animation as primary mediums to contribute to and critique the archive. Music and meditation are her medicine. She is an artist-archivist; a purveyor and investigator of culture. Follow her on IG @angela_n_carroll or at angelancarroll.com.

The Museum of Trayvon Martin: A Meeting Before Labor at Terrault Gallery- Malcolm Peacock February 11, 2017 – March 4, 2017

The Lost in Screens video is available by email request [email protected].

Photos by Ericka Samis, courtesy of Terrault Contemporary.