Let’s return to a tension that came up and then seemed to quickly die down amid the disclosures and discussions of #MeToo. Many people said that what they wanted was an apology from their abuser, and maybe even some kind of assurance that the abuser didn’t go on to abuse anybody else. Many who came forward had not gotten an apology, and felt like staying silent would hurt not only them but also other potential victims. Of course, contrarians streaked through the crowd, yelling that what these people (they usually meant women) really wanted in coming forward with allegations was to destroy the lives of others (usually men)—never mind all the collateral damage that abuse leaves with victims/survivors.

The desire for an apology is also a desire for affirmation of your reality in a world that tries to paint you as a weak liar. To have someone admit that they harmed you can help validate your anger, pain, betrayal. To apologize is the least they could do—though an apology doesn’t mark the end of grief. You also want to see their words embodied. You want proof.

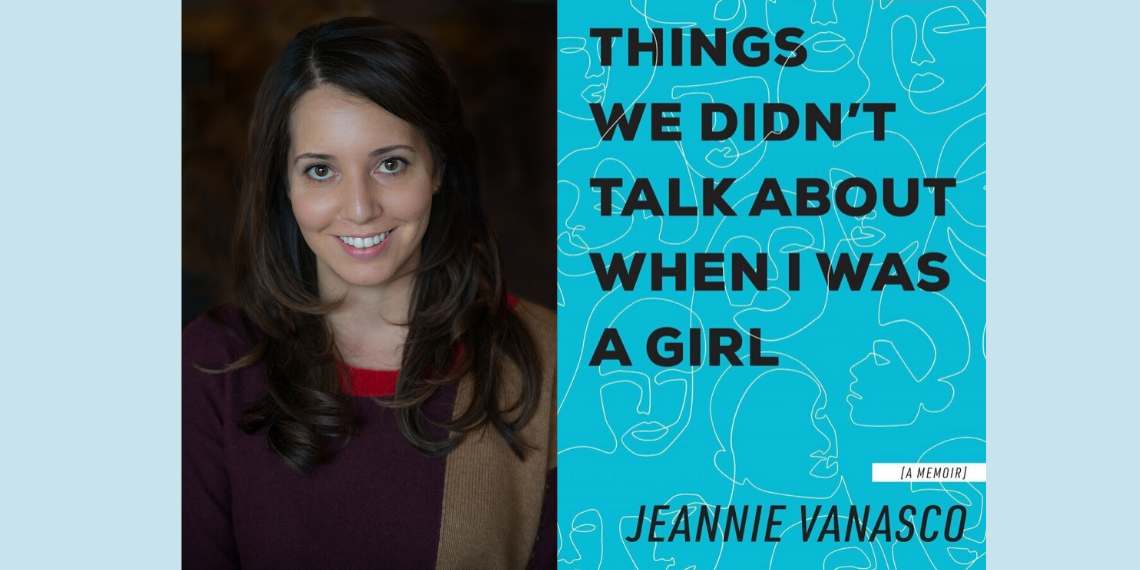

Baltimore author Jeannie Vanasco’s recently published memoir, Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl (Tin House Books, 2019), dwells in that desire for a lived-out apology and underscores the nonlinearity of healing. She contacts her former friend who had raped her 14 years ago, to see if he would talk with her for this memoir project. Bringing her experience into the light of the present, our culture’s lack of support for abuse survivors and the apparent mystery of what accountability looks like are glaring. Maybe the difference now is that these conversations are happening in greater numbers, slightly more out in the open.

Early on in the book, one of Vanasco’s friends identifies a flaw of the internet-based discussions and consciousness-raising of #MeToo: “I think that a lot of what gets shown online is conforming to a very flat intersectional narrative, simply because it has to be flat, it has to be blunt, or else it’s not consumable.”

Vanasco’s narrative is decidedly not flat, blunt, or easily consumable. Hers is written as a choppy meta-narrative: Her back story—growing up in Ohio, her father’s death, her other sexual assault experiences—is interspersed with her own live processing and conversations with friends, her partner, her editor, and her therapist, along with transcripts and correspondences with the former friend whom she calls Mark. (The pseudonym suits the situation because of its brevity, its hard consonant end, and its connotation with a boundary.) Near the front of the book, Vanasco notes that her sexual assault story is not unique. “There have always been Marks, and I doubt they’ll stop existing,” she writes. “Although these Marks rarely apologize for their behavior.” There’s both rarity and reliability here—most people who are sexually assaulted know their assailant in some capacity.

Jeannie Vanasco

“Memories are built to fade, or maybe the brain is built to forget,” Vanasco writes. “But the memory of that night still belongs to me. I wonder how his memory is different.” Two people can have different experiences of the same event, and as Vanasco cuts and pastes the past into the present, she makes room for those perilous differences.

Getting back in contact with Mark sets up an easy ironic contrast. There was no consent that December 2003 evening where Mark carried Vanasco (she was drunk for the first time) into his basement bedroom and raped her. Yet Vanasco agonizes over Mark’s consent numerous times throughout the book—consent to include certain personal but not identifying details about him, consent to record the conversations. She frequently thanks him for agreeing to participate, and tells him she hopes that talking about the assault could help him heal. She even offers to look up therapists for him. After their conversations, she chastises herself for being so humanly grateful, sensitive, and even helpful. That they might both slip into a friendly dynamic is not surprising—they were close through high school and part of college until the rape. The assault did not define their relationship even if it sparked the end of it.

Vanasco doesn’t want the project to be too cathartic for Mark, though. This is not supposed to be a redemption narrative, and she alludes to some ambiguous women here and there who might feel betrayed or take issue with the project on principle alone, interpreting it as giving voice to an abuser, when the whole point of #MeToo is that survivors have been silenced and it is their time to speak and be heard—that giving him a “platform” is repeating the violence.

She soldiers on despite the fear of such reactions. What comes out of these conversations is not a rehabilitative portrait of an abuser—but a rare glimpse of how someone came to do something bad and how it altered his life. Vanasco takes an almost clinical view at what was going on in her life and his at that time, offering to us verbatim what he said went through his mind during the assault. In phone calls, Mark says all the “right” things—he owns up to his actions, says that they changed how he saw himself. Without spoiling it, he calls the rape the “biggest mistake” of his life.

Importantly, Mark also calls it what it was: he uses the word rape before she does. Vanasco struggles to use the word herself, and feels the burden of proof to rationalize—to herself perhaps as well as to the reader—why the word is correct and defensible. Shortly after the assault, she recalls, a friend called it rape, but the word didn’t sit right with Vanasco then. Pondering her choice of words now, she cites the FBI’s changing definitions—at the time of the assault, what Mark did may not have fit under the bureau’s definition of rape as “the carnal knowledge of a female, forcibly and against her will.” But that definition changed in 2013 to include “penetration, no matter how slight” using any body part or object without the victim’s consent.

There is much at work beneath this hair-splitting over terminology. This is how rape culture plays out: victim-blaming and self-doubt inhibit the language we use for our own experiences because we feel like we have to show documents or a license or a state bureau’s definition to validate its accuracy. Vanasco writes through this, too, questioning where she’s seeking validation from and why. She realizes the patriarchal, disorienting way she had been considering the violation of her own body: “All along I judged the assault’s severity based on Mark’s body—which part he used. I never judged the severity based on my body—which part he violated.”

In subtle ways, Things We Didn’t Talk About seems to reference trauma’s insidious effects on the brain. The writer’s worries loop and repeat; she compartmentalizes, avoids, and represses. She is self-aware and occasionally self-conscious—she fears putting so much into the book that the reader thinks they understand her brain better than she does. In offering the reader a look behind the curtain in those talks with her editor and friends about what should go in the book and why, the reader becomes one of several characters that assist Vanasco as she parses, processes, and shapes these recollections into language.

That focus is a strength of this memoir, which doesn’t let characters sit in false binaries like “good” or “bad.” Vanasco wisely doesn’t pretend to be writing a catch-all model for resolution or restorative justice or healing either—having a safe, civil conversation with an abuser is not an option for many. By exploring the complexities of her story, she emphasizes the highly dedicated work required for repair. Our experiences don’t happen in a vacuum, and we don’t have to live through this alone.

Jeannie Vanasco will be on a panel with Petula Caesar and Karen Stefano called “Memoir: Writing the Difficult Story,” moderated by Sharea Harris, as part of the CityLit Stage at the Baltimore Book Festival: Friday, Nov. 1, 6–7 p.m., in the Chesapeake Room of the Pier 5 Hotel, 711 Eastern Avenue, Baltimore.

Author photo by Theresa Keil.