Safiyah Cheatam’s cadence is like that of a poet, soft yet powerful. A visit to her UMBC studio in February of 2020 confirms her engagement with poetry and the human condition. The walls display various texts, such as “If you were truly free, what would your future look like?” and her three-dimensional poetry surrounds me with the artist’s words.

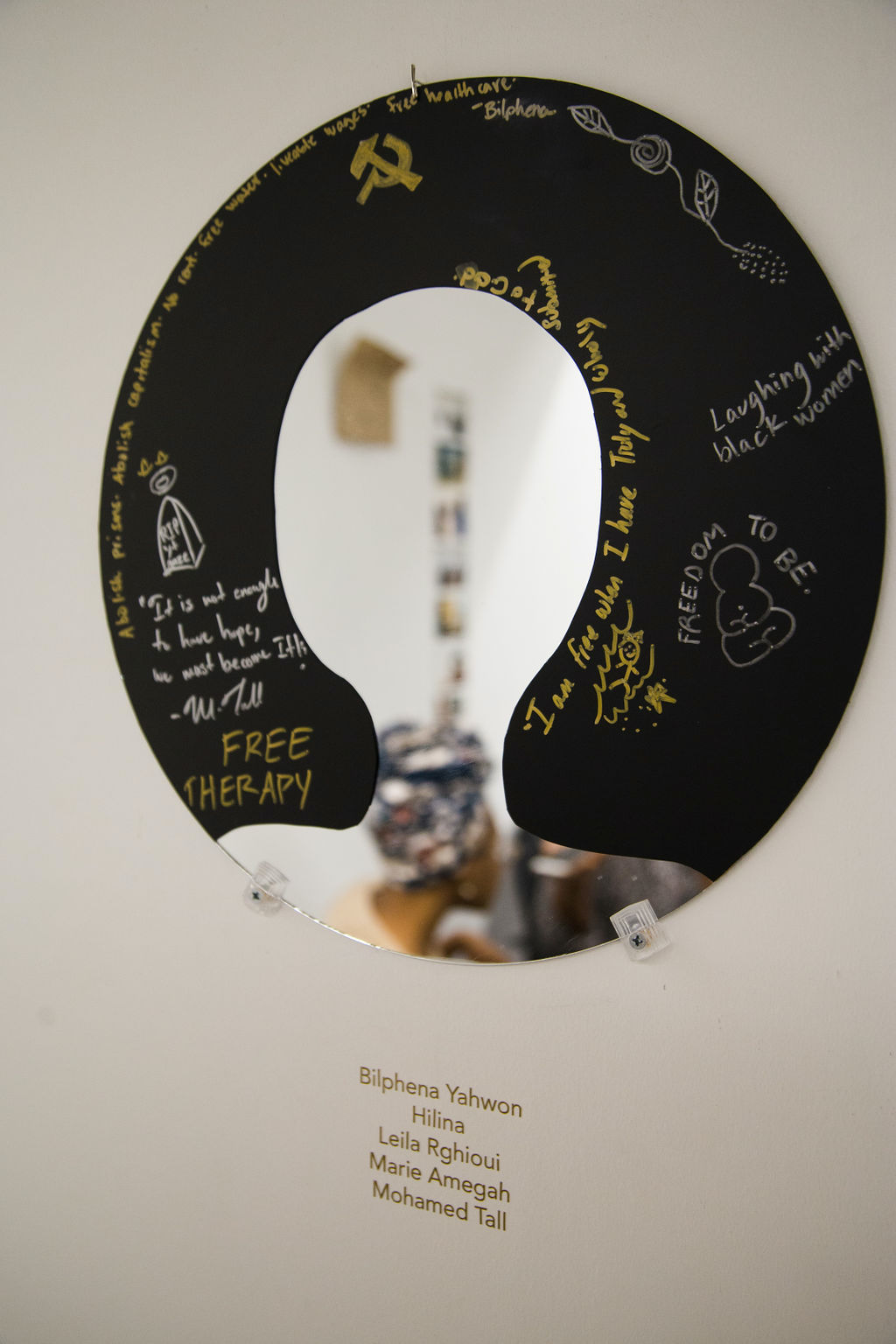

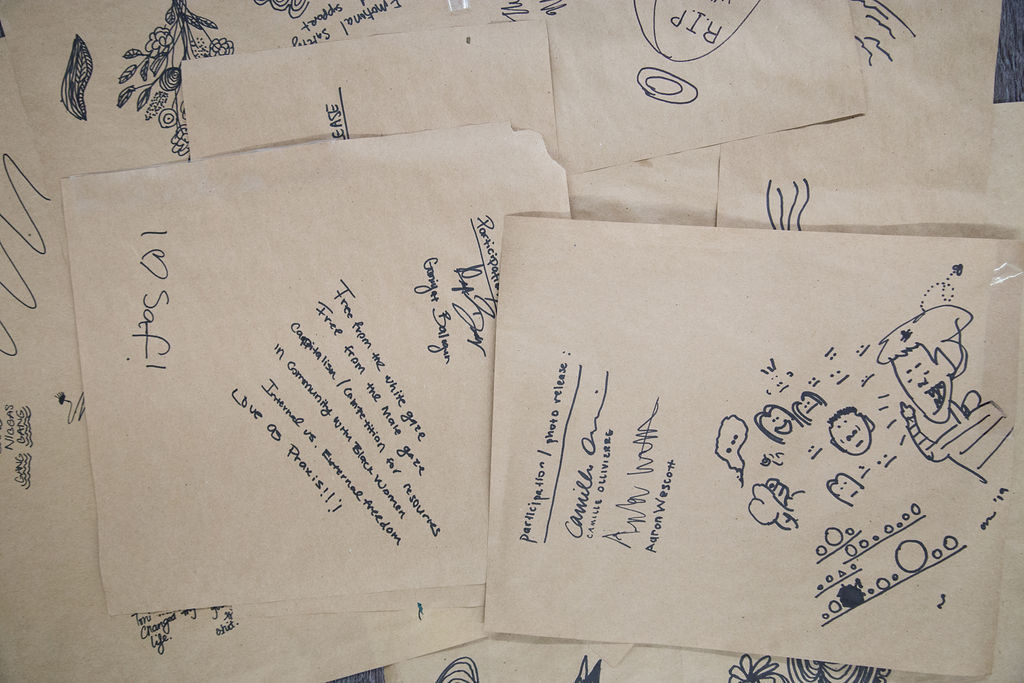

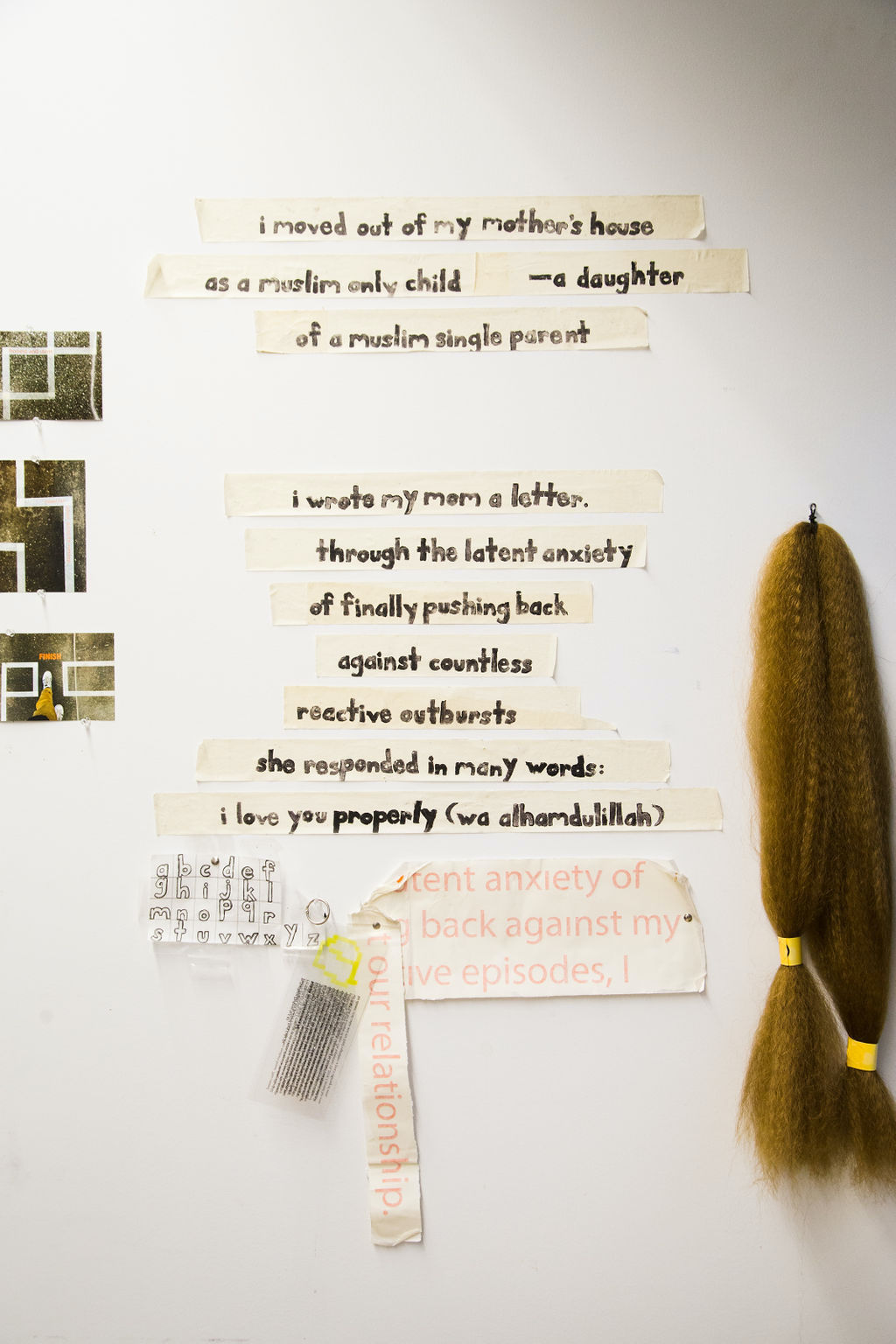

I notice a series of round objects with mirrors creating silhouettes, remnants from a workshop Cheatam facilitated which allowed the participants to see themselves in worlds they imagined. A drawing table covered in brown paper reflects these desires, marked by participants writing their wishes for a perfect world, such as “FREE RENT” and “emotional safety and support.” Another wall features three spiderweb-shaped figures made of braids of synthetic hair, objects with loaded historical implications, especially for Black women.

Before I visited Cheatam’s studio, I had become enamored with her short film #WhenFutureSaid, a compilation of videos inspired by the rapper Future’s lyrics. Inverting the concept of the lyric video—usually a fan-made music video where words are at the forefront—Cheatam instead uses footage shot in response to the words in several Future songs. As an adamant listener of Future, I have struggled with his misogyny, and I was intrigued to see his verses interpreted through film by a Black Muslim woman. The clips show a woman in ordinary settings—drinking tea, applying makeup, and hanging with friends. It’s a compelling engagement with these raw phrases, mainly because I have never witnessed another Black woman’s engagement with rap lyrics in this way.

Cheatam’s #AllRappersGoToHeaven is an amalgamation of red fibers, audio, photos of rappers, and various screenshots of tweets and texts that challenges the boundaries of traditional collage and sampling techniques. The artist describes the piece as an archival-based installation that began online and took on a life of its own through the creation of the hashtag. It is a unique commentary on social media’s ability to gain sentience and extend the lives, legacies, and narratives of those who are a part of it, highlighting the Black Muslim rappers within this project.

With an undergraduate degree in filmmaking, Cheatam initially found it challenging to convert her former film practice—primarily digital and completed on a laptop—into a studio practice with four walls and room for production of more three-dimensional art objects. A lot of her past studio work included mazes, labyrinths, synthetic hair, stamps, references to the self, world making, and Afrofuturism. An aesthetic movement that also serves as a liberatory framework, Afrofuturism traditionally includes narratives that use science fiction to build bridges from the past to the future, through various mediums including visual art, music, and literature. It is an artistic practice that allows Black people to dream and design future worlds and realities.

Much of Cheatam’s practice embraces the imaginary, the radical, and the future. Like Afrofuturists before her, Cheatam carries on the legacy through her evolving studio practice, through her daily existence, and through elements that incorporate her training as a filmmaker, like her podcast OBSIDIAN, co-produced with Adetola Abdulkadir. (OBSIDIAN won a 2019 Ruby Artist Grant from the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation, a significant supporter of BmoreArt).

The piece in Cheatam’s studio that I found most impactful in person is a text-based work displayed on strips of paper stacked horizontally. Consisting of ten lines and printed with hand-carved stamps, it tells of a letter she wrote to her mother. This act of imprinting meaning and truths on a flat medium, with ink and with strength, was a beautiful symbol for the times when you are unable to speak, and then somehow find the strength to convey your message. The content of the letter comes from a daughter explaining a complex decision to a parent, something that resonates with me deeply, as a daughter who lives a life dramatically in contrast to her parent’s desires.

How many of us have texted or emailed or messaged words that we were unable to speak aloud? Through art, Cheatam was able to render the ineffable to a medium that could be interpreted by her mother. Across the studio wall, Cheatam’s words resound, individual characters humming gracefully until a viewer encounters them.

The following interview was conducted in Cheatam’s studio at UMBC on February 24, 2020, and has been edited for clarity.