Carla Du Pree, Writer, Executive Director, CityLit Project

IG: @darkndifferent, @citylitproject

Web: citylitproject.org

The views represented are mine and not CityLit Project.

Where do you live? Who are you quarantining with? How has it impacted you?

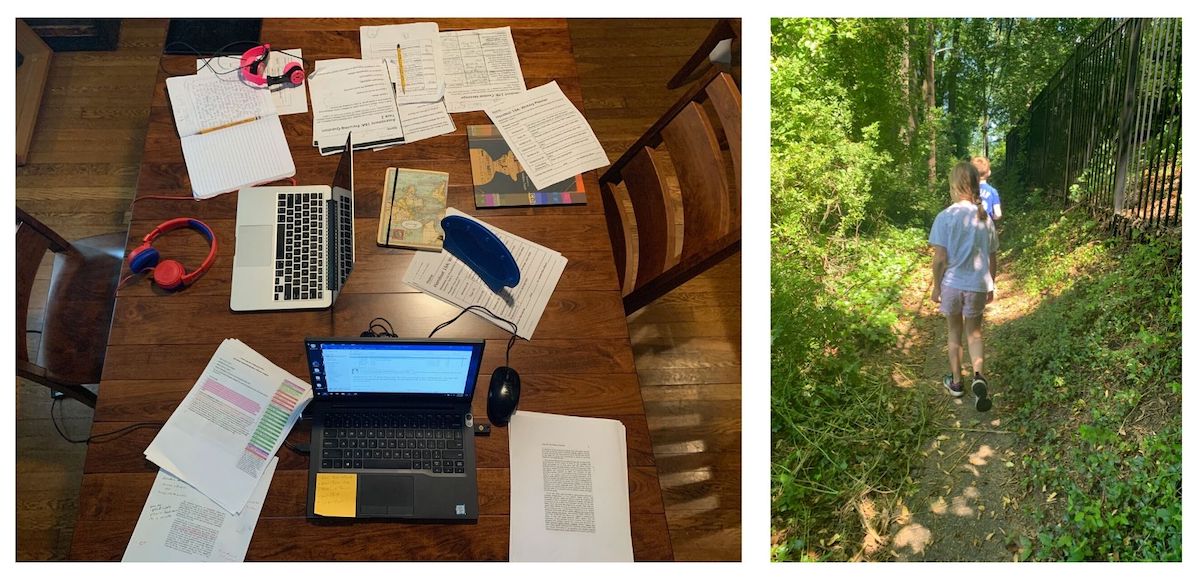

I live in a townhouse in Columbia, and work at the Motor House in Baltimore. When sheltering took place, I was home with my husband of 42 years, my 28-year-old daughter—both of whom began working from home—one of my 25-year-old twin boys, who was finishing his first year of graduate school at Columbia University, and three dogs, Papi, our chocolate lab, Diamond, a softie, blue-nose pit, and Layla, her lovable, ADD pup.

It meant redefining living and workspace. It meant musical chairs for Zoom meetings and a rush to press mute for barking dogs. It meant cooking galore and a lot of emotions teased up especially through those first few weeks. It also meant staying closely connected with my other son and Zoom days with my 5-year-old grandson. That matched with daily construction woes on our street with the replacement of water pipes, meant the street and sidewalks were torn up and the cacophony of jackhammers and backhoes was enough to render us crazy.

What are the three emojis you are using most right now?

The wispy pink heart: There’s so much to love on, including the blessings of FaceTime to stay connected, the circle of family—even in small spaces—my health and a job.

Brown praying hands: There should be several emojis depicting prayer since we all know there’s a difference between praying on your knees and praying on your face.

Brown fist bump: When the words or the feelings speak truth to life.

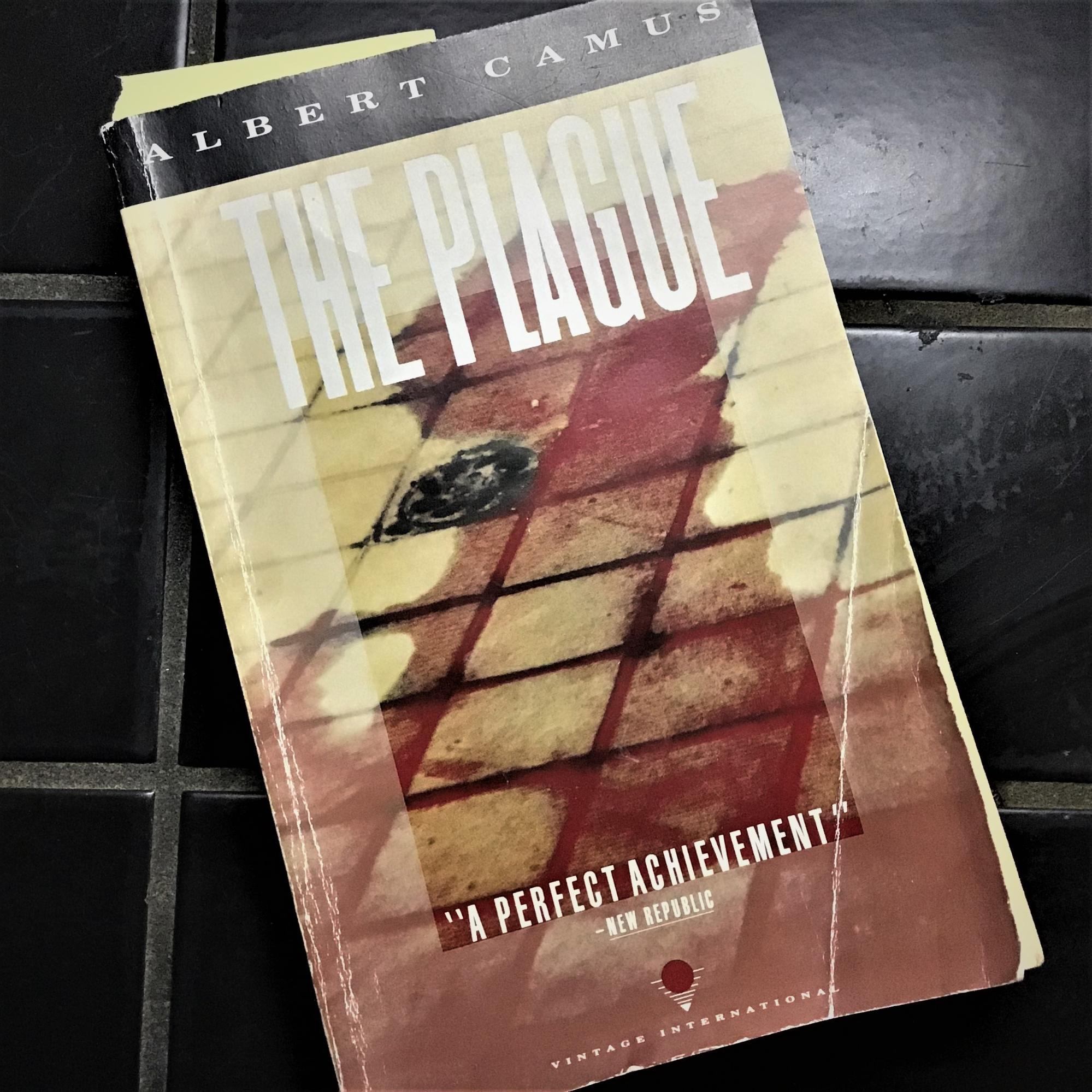

What are you reading? How has a specific author, book, article, or publication impacted your experience of quarantine?

I’m reading everything. I’m reading nothing. While many books have gotten my attention, I’m afraid it’s hard to plant my attention anywhere for long. Call it COVID-While-Black. The immediate onset of the pandemic and how it had us shifting gears at a moment’s notice.

In our household alone we dealt with: (1) the upset of a graduate study moved online after students had to leave campus, where the disparity of poverty and privilege was made prominent; (2) death during coronavirus—a live video feed of a funeral, and the horrific search for my son’s roommate who was found in his apartment having been sick with COVID-19, alone and in despair, who at 26 took his own life. How we grieve during this time will root and resonate for years; (3) And for me alone, the postponement of a daylong CityLit Festival featuring 80 local, regional, and national poets and writers, and 20 frickin’ awesome sessions that would’ve moved you to action on so many topics to list.

I emerged from being a wholly-exhausted lone staffer to the uneasy realization that the fight now was how we stay “alive” through and after the pandemic; (4) The thrust of working closely to stay abreast of my three twenty-something-year-olds and what the dreaded future holds for them being young and gifted and Black in a country that DOES. NOT. PROTECT. THEM, and a grandson who reminds me days after I see but cannot hold him, “I don’t have the virus, Grandma.” Sheltering in place from the onset has had its share of loss and angst, but We’re. Still. Here.

What has been the most difficult for you to adjust to?

What continues to plague me, as someone who thrives on hope and what’s next, before this pandemic took root, I felt complete and utter dismay at how inequities run wide and deep in Baltimore, along with the need for structural changes in some institutions, not “cosmetic diversity.” As a person of color leading a literary cultural institution that is not Black but stands in its power of inclusive voices, don’t think for a minute I haven’t met my set of challenges along racial lines where the expectation is do more, reach higher, but go unseen.

I am a Black woman leading an institution that isn’t exclusively focused on either of those two groups; celebrated, yes, but not exclusive. As much as I have championed inclusion and equity in my professional life, it has become a weight too heavy to withstand, too hard to lift, and too rooted to unearth without others tending to it. I am not alone in saying this. I do enough, but it’s not enough. Witnessing this country come undone by a trail of brutality, past and present by the men in blue, is just part of the national conversation. Racism and inequities—as subtle as they can be—exist everywhere, but this kind of violence forces Black Americans to live between rage and grief.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. As if watching George Floyd lay on the ground, a knee pressed on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds wasn’t enough, what broke me was when he called for his mother, and EVERYTHING in me wanted to save him. To. Save. Them. All.

Many think these riots are just about Floyd, but it’s so much deeper than that. When you unpack the stories of Breonna Taylor (don’t get me started on the perpetual violence against Black women in this country), and the fact that those no-knock cops shouldn’t have been in her home in the first place, in search of someone who not only didn’t reside there but who had already been apprehended, it’s a travesty of justice. The tragedy of Ahmaud Arbery, as old as my twin boys, gunned down while running in a video I refuse to watch. How is it possible it took so long to arrest the perpetrators? From the Amy Cooper story of the white damsel in distress who knew her rising plea to the police would render her protection and Christian Cooper’s potential death. (Have you forgotten the Central Park Five?) To the lesser-known story of Monica Shepard in Pender County, North Carolina, a mother who fought off an armed off-duty corrections officer and his posse, his foot wedged in her doorway as he demanded her 18-year-old Dameon give himself up. A senior graduation sign on the lawn bearing his name, Dameon loudly chanted his name over and over again—and the crowd would come to understand he was NOT who they were looking for. Sometimes I wonder if it’s better to just wear the white hood. At least we’ll know what’s coming.

Regarding the riots and the mass destruction we are witnessing right now, who among us can stand in our truths and say we’ve walked in those shoes and met that kind of despair where you’d take to the streets with balled fists? I mean those who’ve been given up on with no way to make a decent wage, who live in food deserts with inadequate transportation, who act like they have nothing to lose, who survive in the world of the not-enoughs. Not enough money, not enough experience, not enough security. America, your history is showing. I don’t condone violence, obviously, but as you stand in your privilege, who among us can say how anger should manifest itself when that knee isn’t on your neck?

The tragedies before Floyd didn’t get the world to pay attention, but his story became the straw that broke this country’s back, and here we are, a lit tinder box of rage. Story after story, year after year didn’t lend itself a way to right the wrongs.

Never mind the fact that we are in the midst of a global health crisis and the number of blacks dying from COVID-19 in our cities haunts us, nor the tragedy of living in an America who tends to love your black culture but not your black skin. When people tell me it’s the perfect time to write and to finish my book or to enjoy my time at home, I give it a pregnant pause. The black writing circles I belong to are numbed by this experience, faltering like me, stricken by how we got here, grappling with how this country has been brought to its knees by racial discord once again?

In our house, we stay in close touch with our elders. My parents were born and raised in ‘Bloody’ Lowndes County, Alabama, the bedrock of the civil rights movement, at one point the most violent place in this nation. My husband’s grandfather traveled through the south as the driver, working to convince grocers to purchase the Pittsburgh Courier to grocers with his white-skinned, grey-eyed colleague as a passenger in the back seat, passing. His uncle Rev. Jimmy Joe Robinson marched frontline with Martin Luther King, Jr. In our lifetime we still see it coming, these modern-day lynchings, in the wake of social media where we get to experience upfront racism at work. Where photos are posted of knee-kneeling cops. 8 minutes, 46 seconds. Click. Unprovoked shootings inaction. Click. In a car in front of our children. Click. In our bedrooms, our homes, and on the street. Click. Click. Click.

As a closet introvert, I could see managing my shelter-in-place time in somewhat of a blanket bliss, if it wasn’t for the fear of how to keep a salary and health care past six months, how to pray my way through this with three willful children who are easy targets, while I try to stay home and stay safe, uplifted in my own privilege of having a salary, for now, and health care, for now. Make no mistake about it, no one in my house is sleeping and breathing normal. We don’t even know what that is anymore.

… you asked.