I am so extremely not a scary stories person that it’s kinda funny. There’s a stretch of road in my hometown that I’m still unnerved by because one night when I was a teenager I dropped off a friend at her house after we saw the 2010 remake of A Nightmare on Elm Street and I had to drive home alone. Nothing happened on the drive—I probably drove past a creepy cemetery—but a small, irrational fear haunted me the whole way. Another time, a few years ago, coming home from a party, my roommates suggested we watch the French horror movie Martyrs. “You’ll be fine,” they said. After about 30 minutes of that I had to run upstairs to my room and cry.

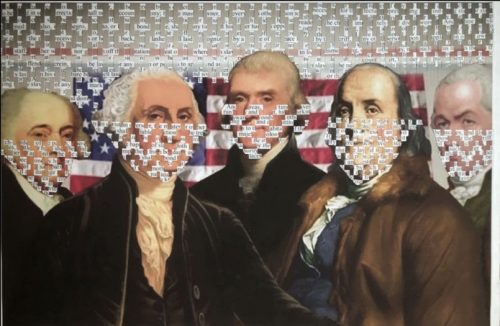

One of the only movies I’ve had the patience to sit through since the start of the pandemic, though, was Parasite. I know it’s not technically a horror movie, but it is violent and gross (and sad and funny) in its depiction of class anxiety, wealth disparity, and desperation wrought by late capitalism. It resonates with all the real-life horror we are drowning in now.

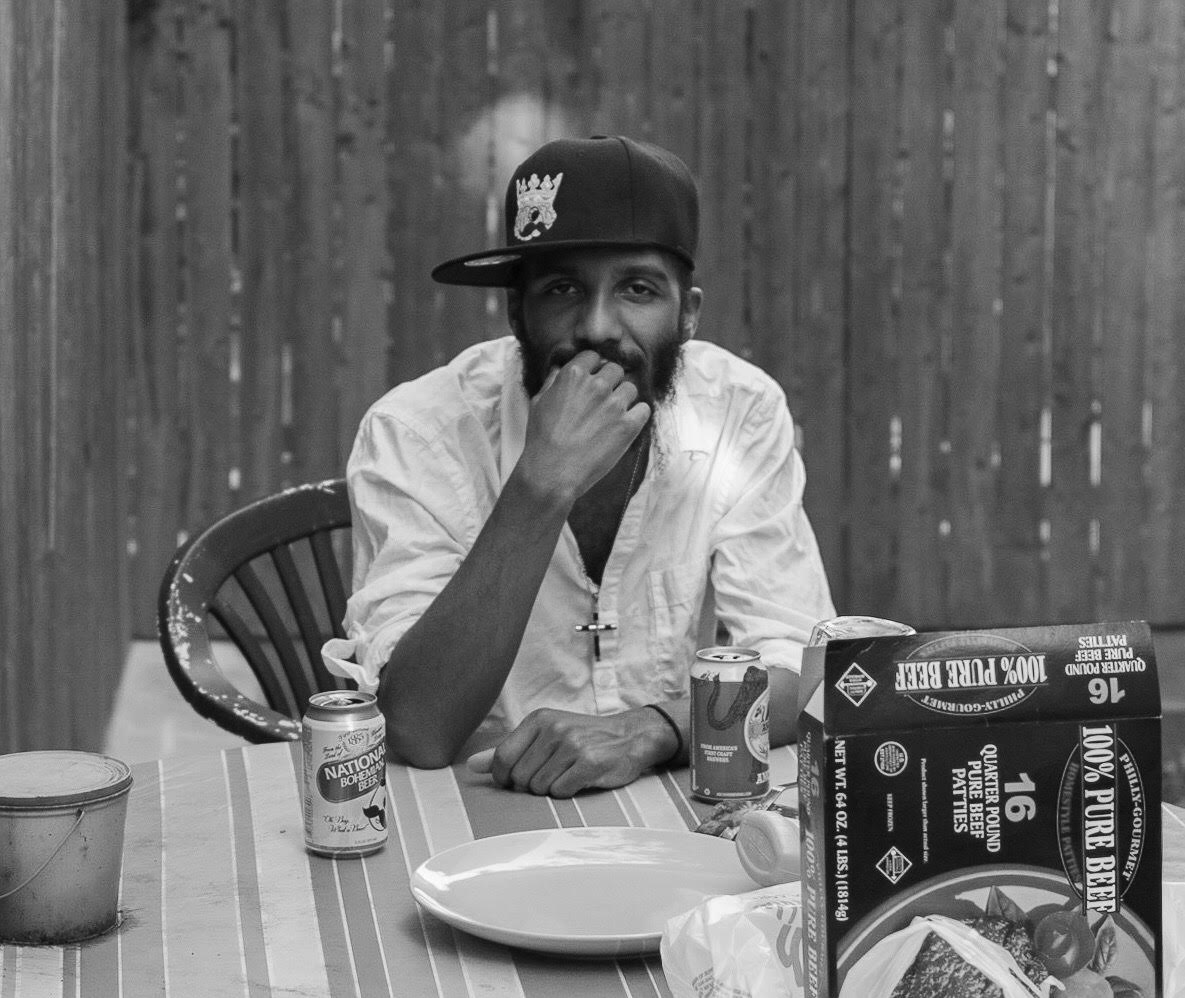

So, with a moderately strengthened stomach, I eagerly awaited The Horror Is Us, an anthology of short stories edited by Baltimore-based writer Justin Sanders and published this month by Mason Jar Press. Sanders originally wanted to compile a book of “social horror” stories, which he saw as “stories that went on the attack and delivered social commentary bathed in blood and black magic or something,” as he describes the concept in an editor’s note. He quickly realized that although he still likes that idea, “a book composed entirely of in-your-face commentary and analysis would have ended up feeling too heady for me, treating fear as something to be observed and critiqued rather than felt. I focused instead on horror that invited me to feel fear with the characters.”

That move toward the immersive and affective rather than the distant and intellectual works well for this slim collection of nine stories by authors around the US and Canada. Abstracting and analyzing fear can be useful in a therapy session, but it’s not always what we want from art.

And maybe there is value in facing our own fear of fear. So over the course of a week, I ate up a story or two from The Horror Is Us each night, settling into these sick, fictional worlds that occasionally mirrored our sick, real world. Even if Sanders is uncertain what “social horror” means exactly, the term feels appropriate for a suite of stories that reference sexual assault, police violence, economic precariousness, familial dysfunction, and much more. The book also contains a range of tactics: while some stories use elements of body horror and gore and the supernatural, others create more psychologically disturbing moods.