Jazz and collage are two seemingly unrelated things that I know are absolutely related. I listen to Miles Davis’ “Blue in Green” whenever I need a little help pushing through writer’s block. With the disorienting amount of racism and the ugly innards of white supremacy fully on view for the world to see last week, I struggled to focus. But listening to Davis on repeat seems to unlock some kind of cheat code that allows me to move past anxiety and write through it.

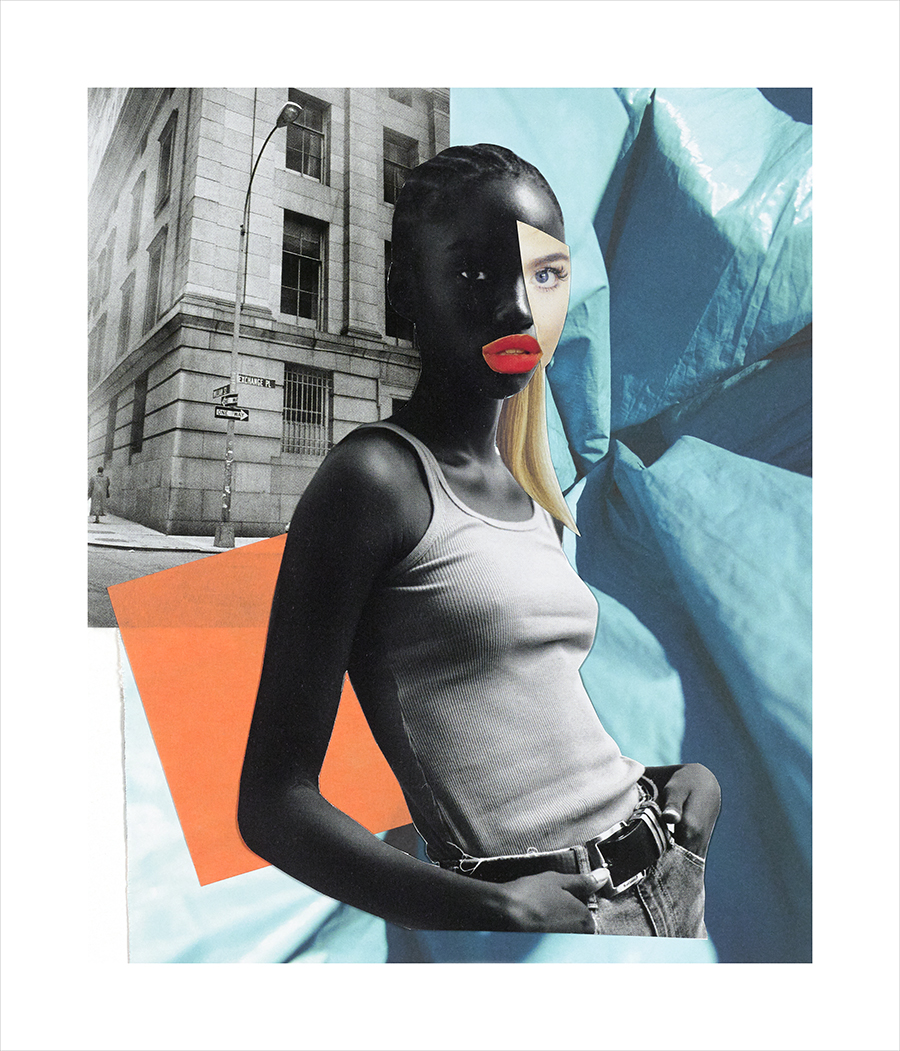

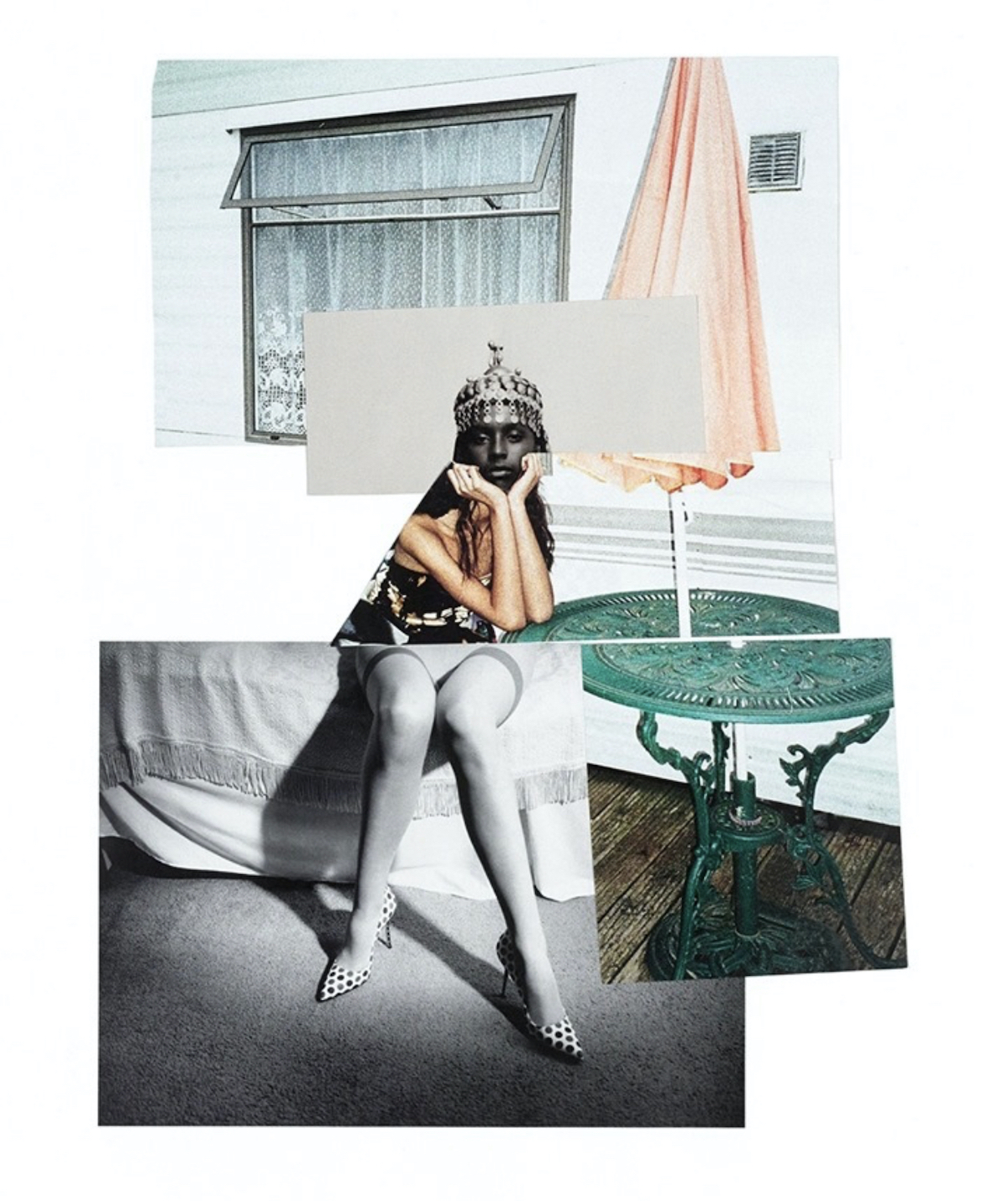

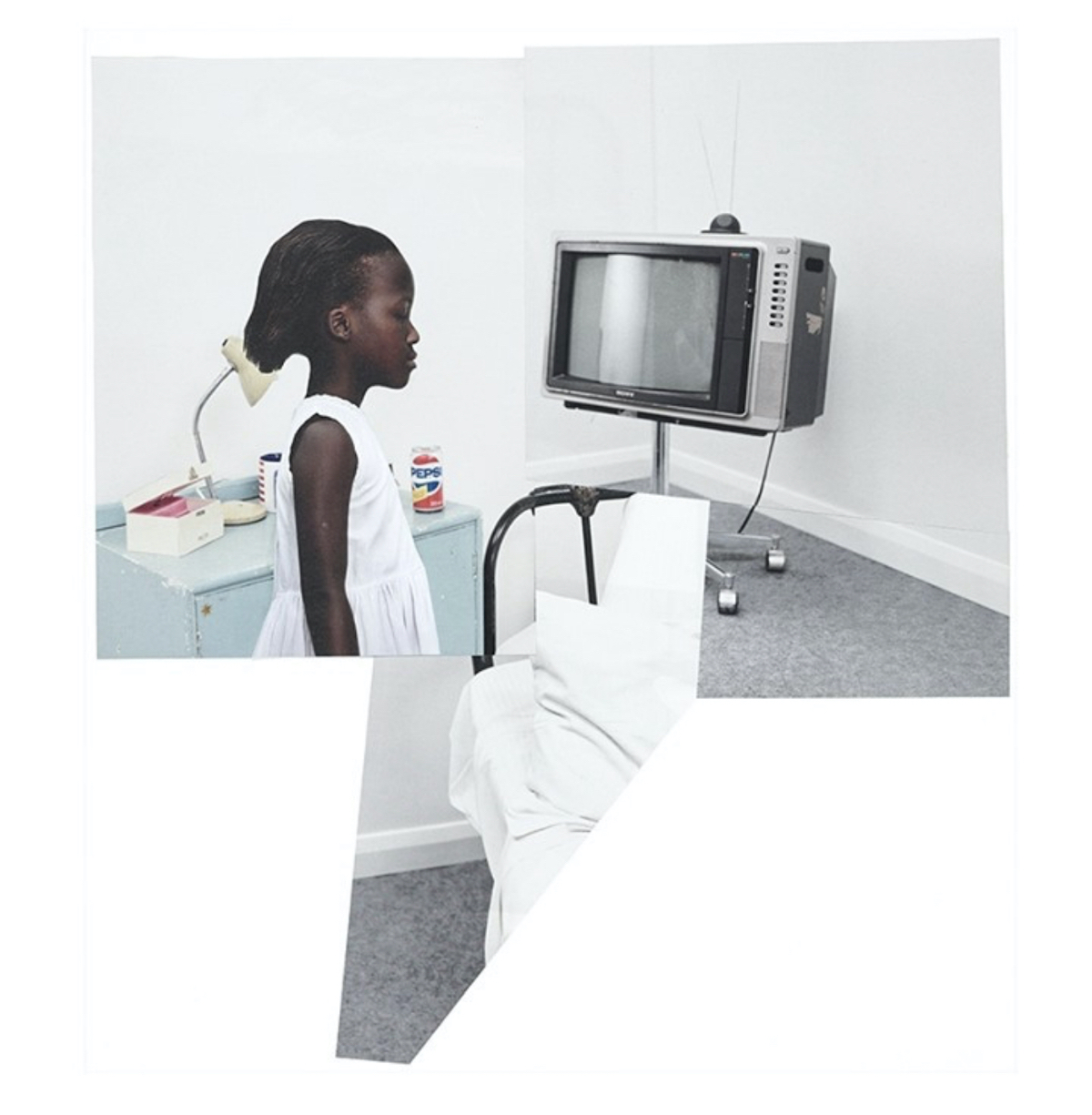

Romare Bearden’s collages are like remarks of visual poetry and tactile personifications of jazz notes on paper. In “The Genius of Romare Bearden,” Elizabeth Alexander writes: “Collage, in both the flat medium as well as more abstractly in book form and as a metaphor for the creative process, is a continual cutting, pasting, and quoting of received information, much like jazz music, like the contemporary tradition of rapping, and indeed like the process of reclaiming African-American history (or of any historiography).”

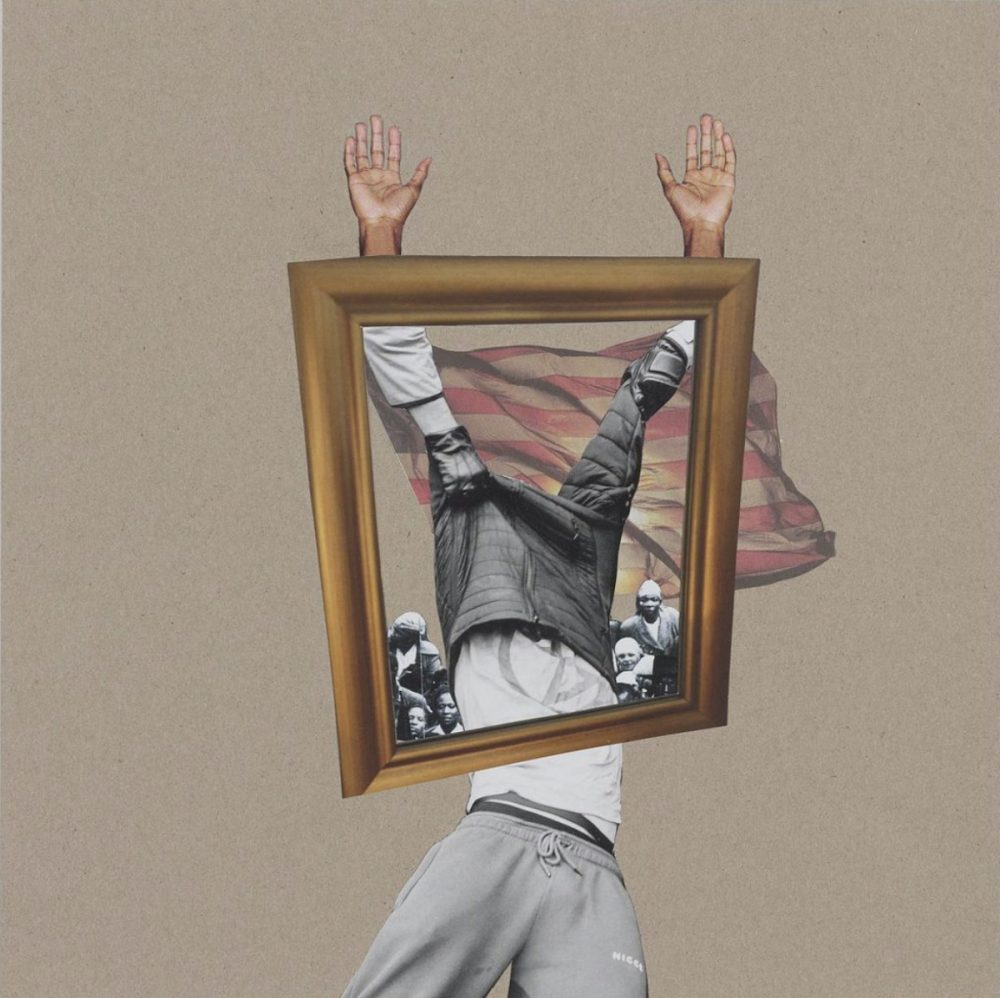

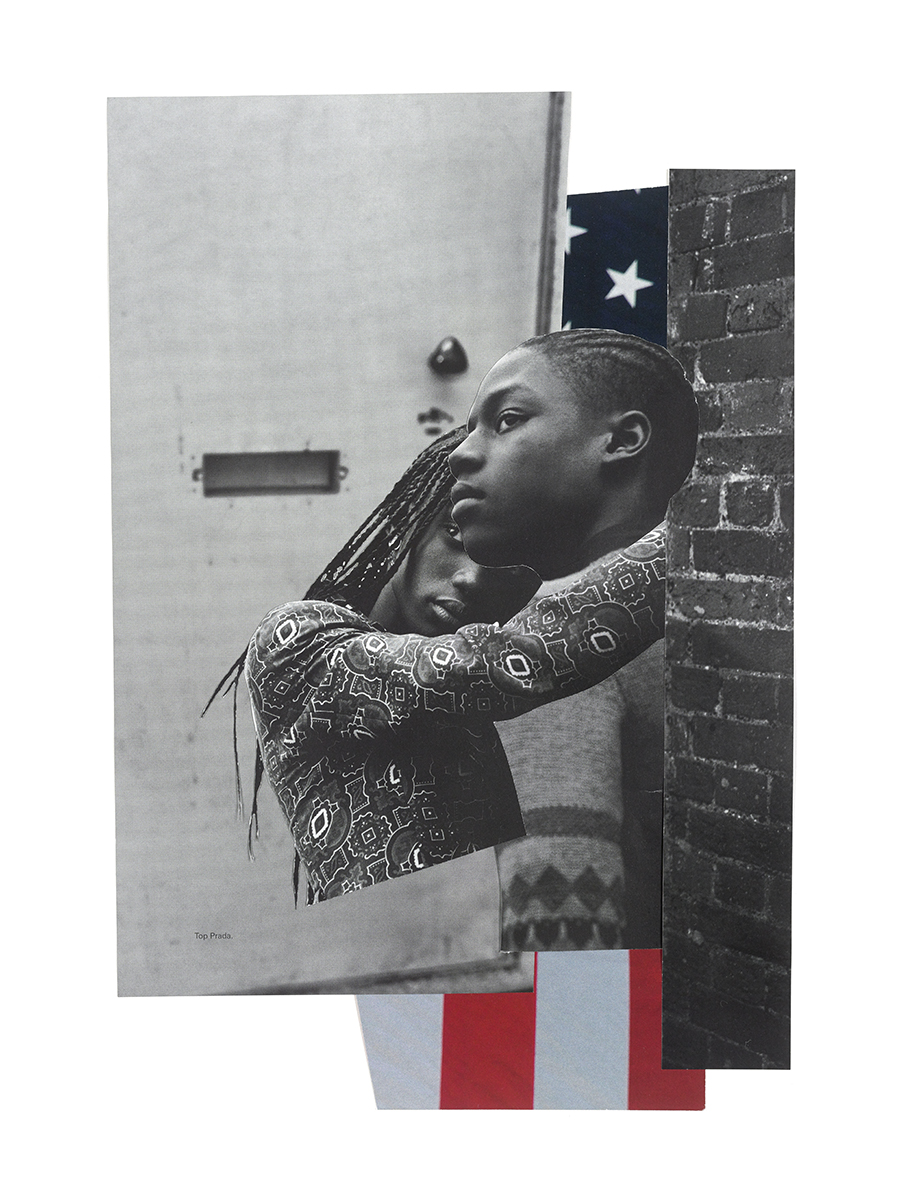

Collage can imply a flat surface, like the twelve paper pieces Bria Sterling-Wilson created for her solo show at Full Circle Gallery, Issue No. 1. It can also refer to various processes of creative alchemy that have been passed down through generations of Black families. Our ancestors made quilts from pieces of discarded materials, they composed songs without formal training that birthed entire genres or creative musical expression, and from discarded scraps of food they created sustenance.