How long have you been working on this project? There is so much work in this show, and the whole thing is so dramatic in the way it is displayed. When did you start this project and how has your thinking and output changed?

The oldest artwork displayed at the ORBIS TERTIUS -Hlaer to Jangr– exhibition is “THE PIG,” the black and gold inflatable sculpture located at the backroom area of the exhibition. This specific piece was created as part of my MICA thesis show in 2014, and I included it as a tribute to my student years, and to reference the visual catalog of misplaced artifacts that this universe is capable to contain. The rest of the exhibition covers eight years of work, although about half of the content was created in 2021.

Interestingly, Elgreen Project has been officially existing since around 1998. I can say, without a doubt, that the project has completely evolved since its humble beginnings. But this particular exhibition, ORBIS TERTIUS -Hlaer to Jangr-, has shown me what the future of my work will be like.

You now live in Baltimore; you came here to attend MICA for graduate school and you now teach MICA students. How has Baltimore changed you as an artist? How has your perspective as a transplant informed the way you think about Baltimore? For example, what do you know and want to share with Baltimore, from living elsewhere, that people here should know or consider?

I spent two of the best years of my life pursuing my MFA at MICA. Coming back to Baltimore and working as a full-time teacher in the FYE (First Year Experience) department at MICA has brought me to a full circle, and a new beginning. As a fun fact, I graduated with an MFA in Illustration Practice, but the running joke with my Mount Royal and Rinehart friends back in the day, was that I am NOT an illustrator, but a sculptor in disguise. I take that as a huge compliment.

Regarding the city of Baltimore and what people should know, I think the tight-knit community of artists living in the city is by far one of the most incredible things about it. “Smalltimore,” as it is lovingly referred to, is not an exaggeration. Becoming part of the welcoming artistic movements in the city is truly a gift. Being surrounded by incredible artists in the city feels almost like a commitment to represent the area, and at the same time, the perfect place to raise a voice to make our community visible through amazing art.

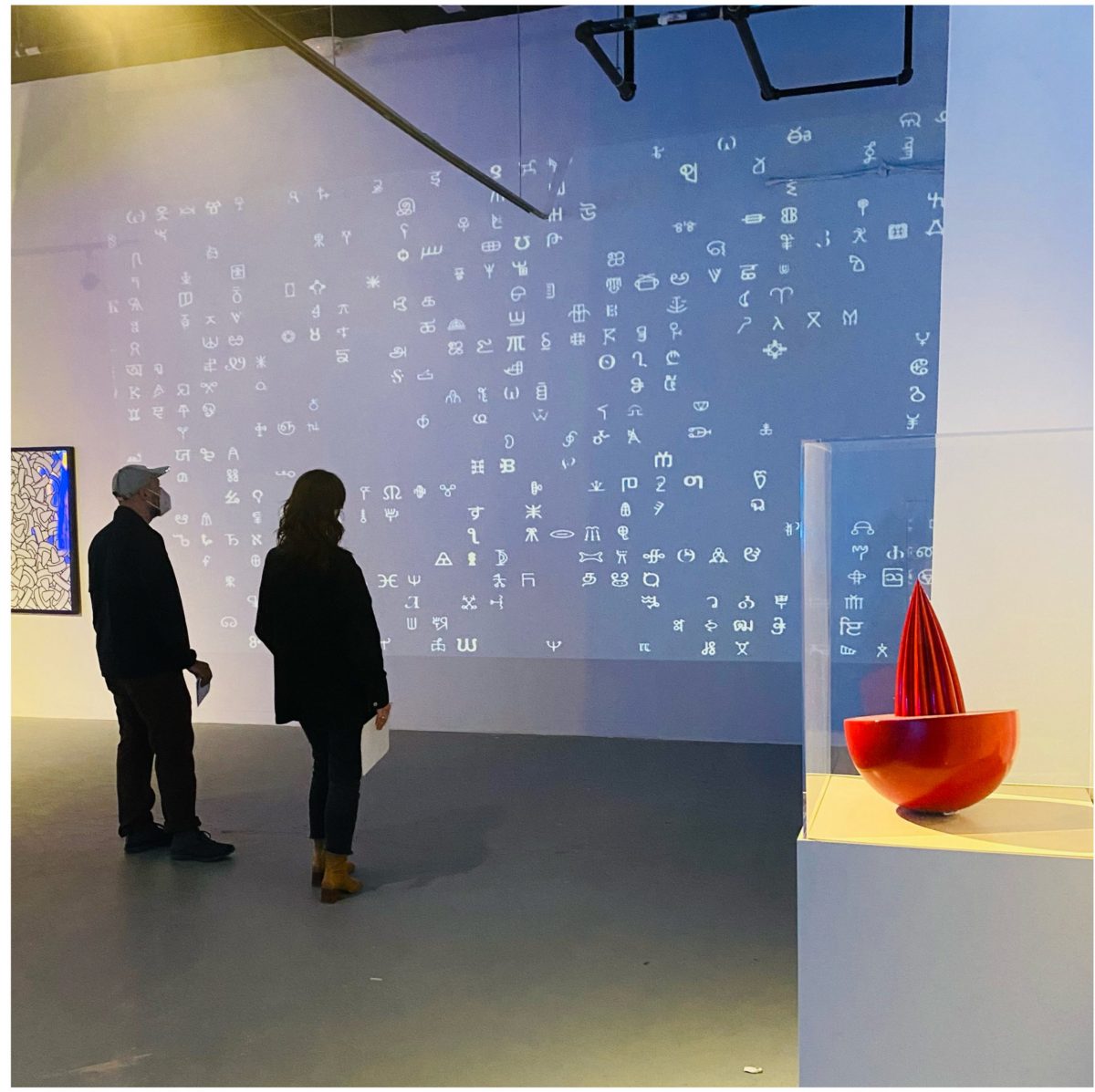

In many ways, this poetic exhibit is about language, literature, and the collective epic mythologies that govern our consciousness, as individuals and as larger groups.

The multisensorial nature of the exhibition is an unavoidable invitation to get lost into oneself. In addition, the premise of my work grants the viewer freedom to interpret its meaning. The language I use at the exhibition (both literal and metaphorical) is constructed on the same pretense.

The materials involved in this exhibition include such a wide variety—it’s mind-boggling. Can you talk about your favorite materials, many of which appear fabricated, and how you use specific types of materials for an intended visual or emotional effect? (For example, giant inflatables vs. small ceramic versions of the same shapes, or the impact of neon and glowing laser-cut “signs” with interior light sources)?

I think of my work as an ongoing exploration of materials and processes that tries to find the best way to express a particular idea. A good example of this principle are the neon signs at the exhibition. It is very easy to associate neon and logos to a specific time period. Neon signs were widely popular in the ’60s and I purposefully capitalize on this allusion to instill an anachronistic feel to them. Therefore, the selection of materials is intended to generate both a visual and an emotional effect to the viewer.

I really cannot say that I have a favorite material to work with (although I LOVE the aesthetic of shiny vintage plastics). But on the other hand, I DO have a few favorite methodologies for my projects. As an illustrator and designer, I often find myself challenging the limitations of two-dimensional art.

The extensive use of vector-based software in most of my work has inevitably created a bridge that connects the two-dimensional work with more “hands-on” manufacturing processes. With this approach, the gap between “the image on the screen” and “the tangible” is virtually invisible.

A clear example of this type of process in my work is the use of laser cutting technologies over wood or acrylic sheets, as the immediate outcome suggests the possibility of a “puzzle.”

In relation to the criteria of scale, material, and iteration, a good example would be the artwork I call “Artillero” (or as artist Sasha Fishman called it, “a sophisticated red lemon squeezer”). This sculptural object, created in collaboration with the amazing artist Pete Karis and Paradise Labs, is first introduced in a process involving two main components: a hand-polished styrofoam half-sphere and a subsequent 3D-printed grooved cone glazed in red automotive paint. This is later translated into a large-scale inflatable sculpture iteration of the small-scale model, constructed with 500D Nylon. This dramatic shift of scale is, of course, deliberate, and is intended to generate a disorienting effect in the viewer. In addition, the thoughtful placement of the small artwork in the gallery space, followed by the large-scale model in the basement, is created purposefully to contrast the narrative of the real world (Baltimore) to the secret dimension that lurks in the spaces beyond the gallery walls.

As one last example of “iteration and emotional effect,” I would like to highlight “Funes” (the intimidating character based on Borges’ Funes el memorioso story, that inhabits the abandoned bowling alley). What started as a vector illustration later became the complex endeavor of translating the geometry of the head of its protagonist to a life-sized 1:1 helmet capable to fit an actual head. This was particularly challenging, as the project was developed between countries (México-US) in teamwork with the architect Salvador Amaro, via ZOOM calls, measuring the body in the US and 3D printing and assembling the “omnidirectional head” in México.

The precision of the project was incredible considering the long-distance collaboration, and the result was uncanny, successfully capturing the distinct eeriness of the pivotal character of the show.