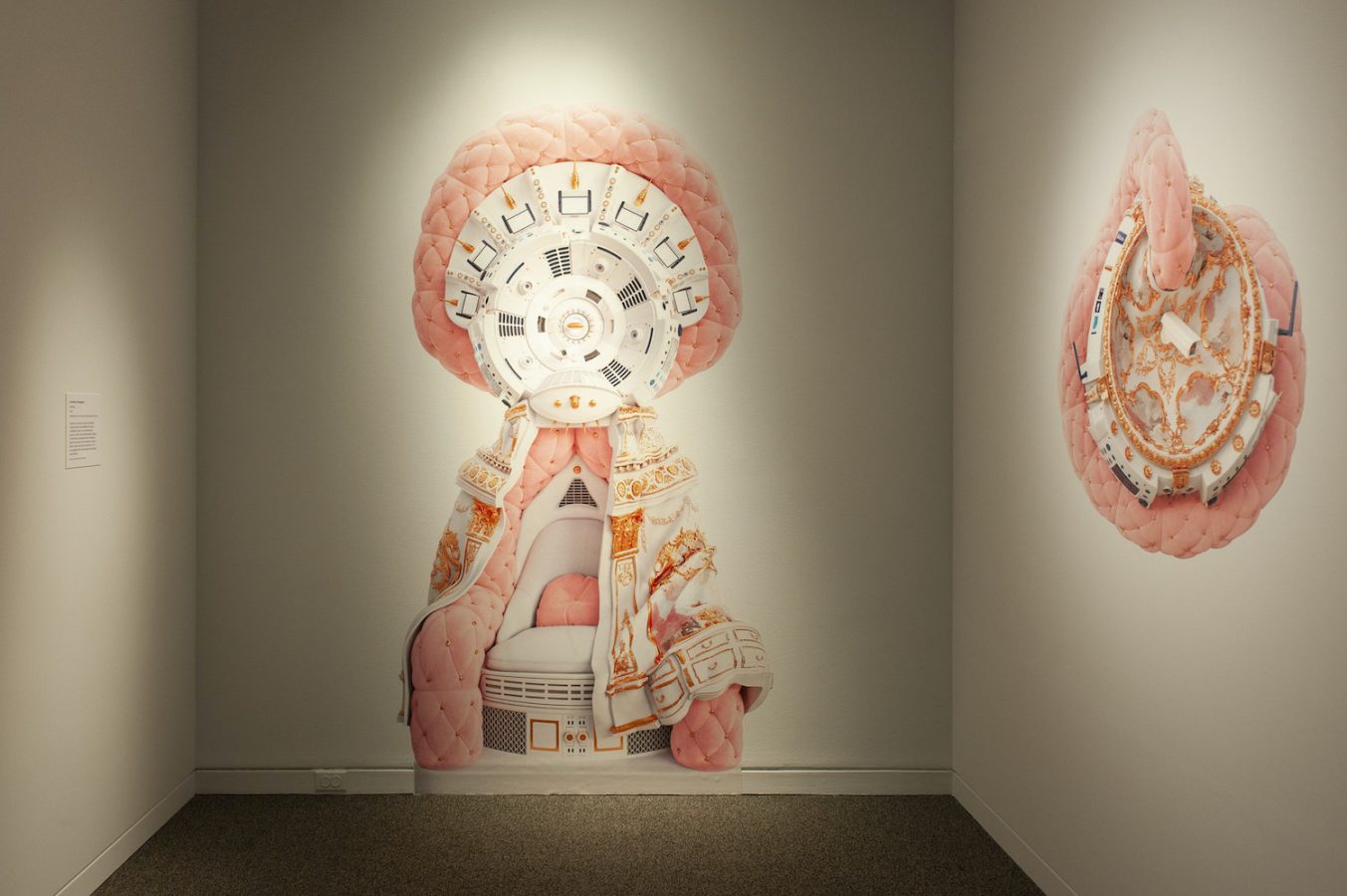

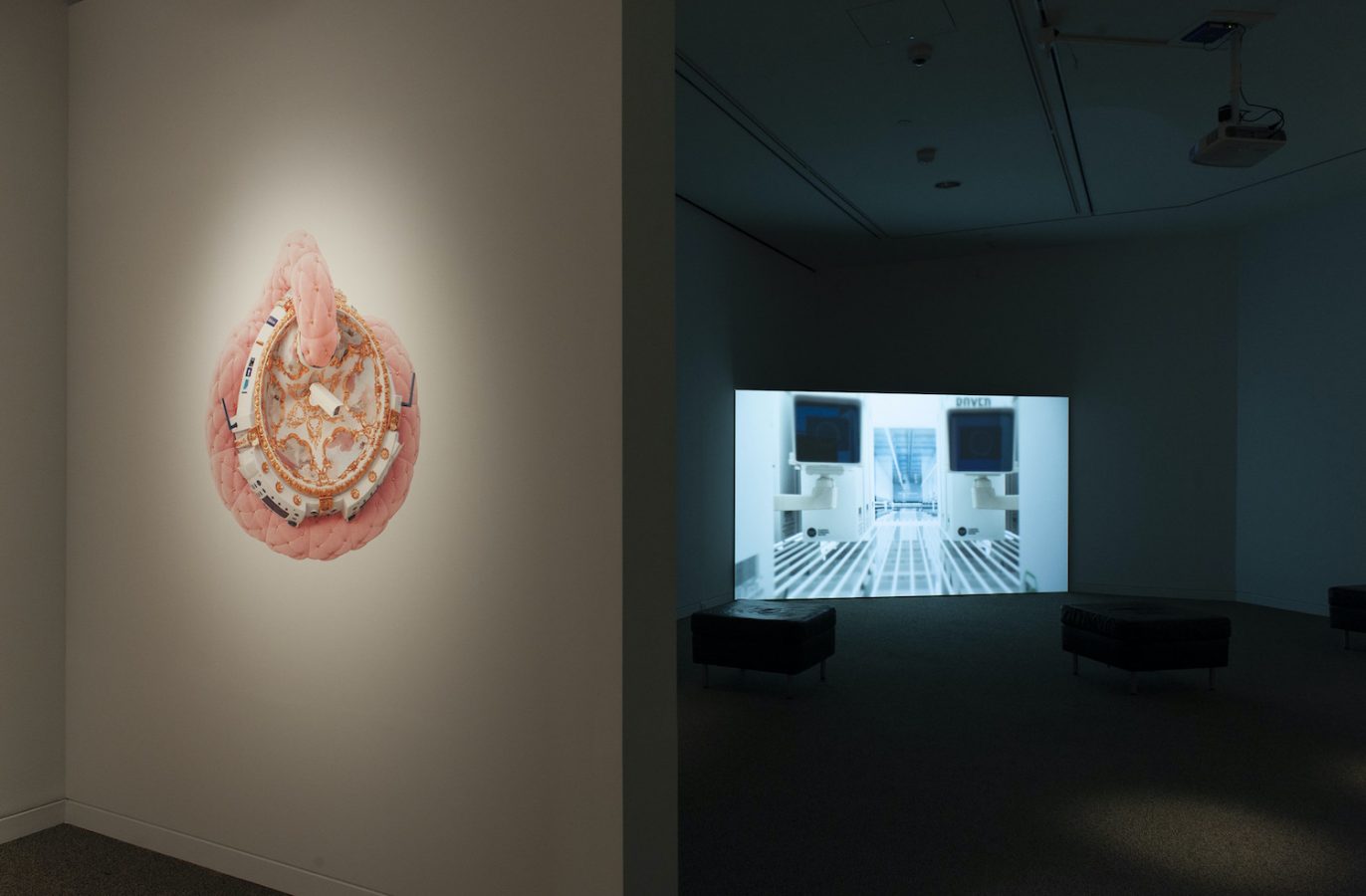

Monaghan’s Sondheim finalist exhibition space at the Walters Art Museum contains only two works, “Den of Wolves,” and a wall decal work, “Sentries IX,” which is from a series of works made using the same software as the animation. The “Sentries” series plays with texture and color, combining Baroque art and architecture with soft-looking pastel fabrics, a melding of the gaudiest moments in art history with contemporary technology.

Monaghan, who received his BFA from the New York Institute of Technology in 2008 and his MFA from the University of Maryland in 2011, lives in Washington, DC, and is represented by bitforms, a New York gallery dedicated to showing the work of contemporary artists exploring new technologies (this video work and others are part of his solo show, closing June 12 at bitforms). Monaghan’s work has been screened and included in group shows all over the world, including the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, among many others. Notably, his work has been recognized with residencies at the Millay Colony in New York state and Palazzo Monti in Brescia, Italy, and he was the 2015 recipient of the Trawick Prize.

Monaghan’s themes of power, technology, and rampant consumerism speak to the unique challenges of today’s attention economy. Nobel Laureate economist Herbert A. Simon first used the term “attention economy” in 1971, but it has enjoyed a resurgence of popularity thanks in part to Jenny Odell’s 2019 NYT-bestselling self-help book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. In her book, Odell, an artist, educator, and millennial, discusses a wide range of subjects from the intentional off-the-grid communities of the 1960s and ’70s, to alternative social media platforms, to resistance and advocacy groups like the student survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, as a means of demonstrating what can happen when we engage intentionally with the world around us.

Odell writes that “attention economy distractions keep us from doing the things we want to do . . . they keep us from living the lives we want to live.” Social media surveillance and the way marketing algorithms now function seamlessly to show us items we want to buy are the problem, she posits. Perhaps “airplane mode” and birdwatching are the answers, she suggests.