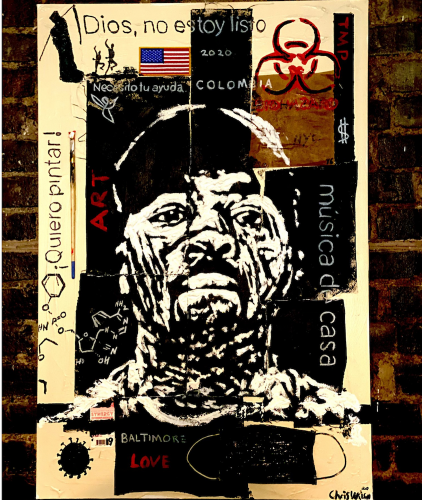

Photographer SHAN Wallace has a habit of making sure that the portraits she takes end up in her subjects’ hands. Journalist Lawrence Burney shares and writes about Baltimore history, often through its music. Having known and worked with both Wallace and Burney for several years, curator and artist Ginevra Shay was deeply impacted by the generosity of their work and wanted to support them in an innovative and generative way. “I was thinking about how committed SHAN and Lawrence are to people in Baltimore,” Shay says.

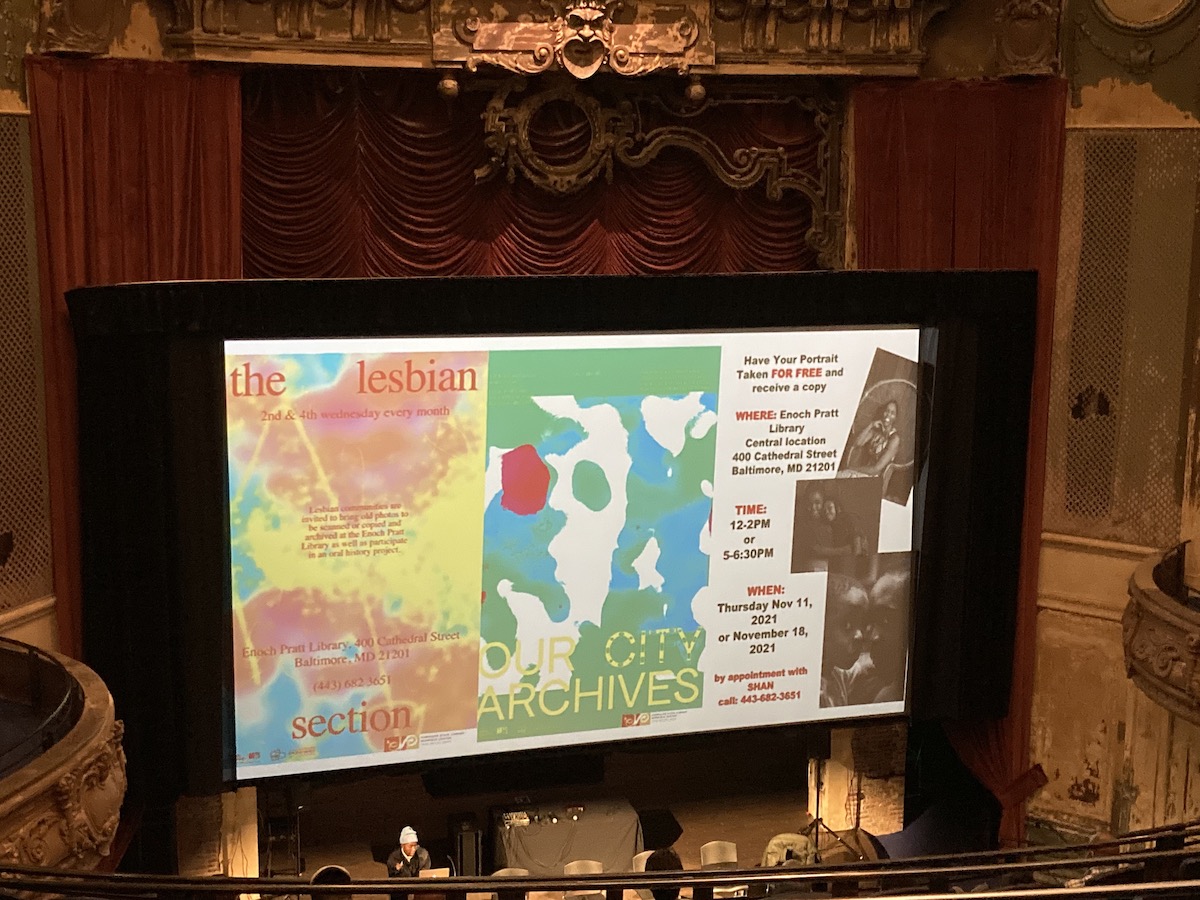

In collaboration with Wallace and Burney, Shay developed Baltimore Living Archives, a year-long residency hosted jointly by the Enoch Pratt Free Library and the SNF Parkway Theater. The residency, currently organized by Parkway programming consultant Mia Smith, gives artists access to the Pratt’s archives as well as the Parkway’s resources, along with the ability to publicly present their research. Both artists are recording oral histories during the project, which enables the creators to simultaneously deepen their practices and bring community members into the fold, to have their voices heard and be welded into a record of Black Baltimore history.

Baltimore Living Archives was developed with care and clarity, with the idea that resources should be allocated to Baltimore denizens and that artists/archivists should have financial support for their research. Working for three years as The Contemporary’s artistic director, Shay witnessed the impact of an institution giving artists material resources to push their work further. Curating exhibitions at The Contemporary, working in archives at the Jewish Museum of Maryland and the Afro-American Newspaper, and researching at the Enoch Pratt Library and the Maryland Historical Society reified for Shay the fact that archives are both critical and under-utilized. “I just came to a realization that archives were vital and important to Baltimore’s culture and history, and any place’s culture and history, and they need to become accessible,” Shay says. “People need to know that they’re there, that they’re a resource for them, that they can engage with them, that they are for them.”