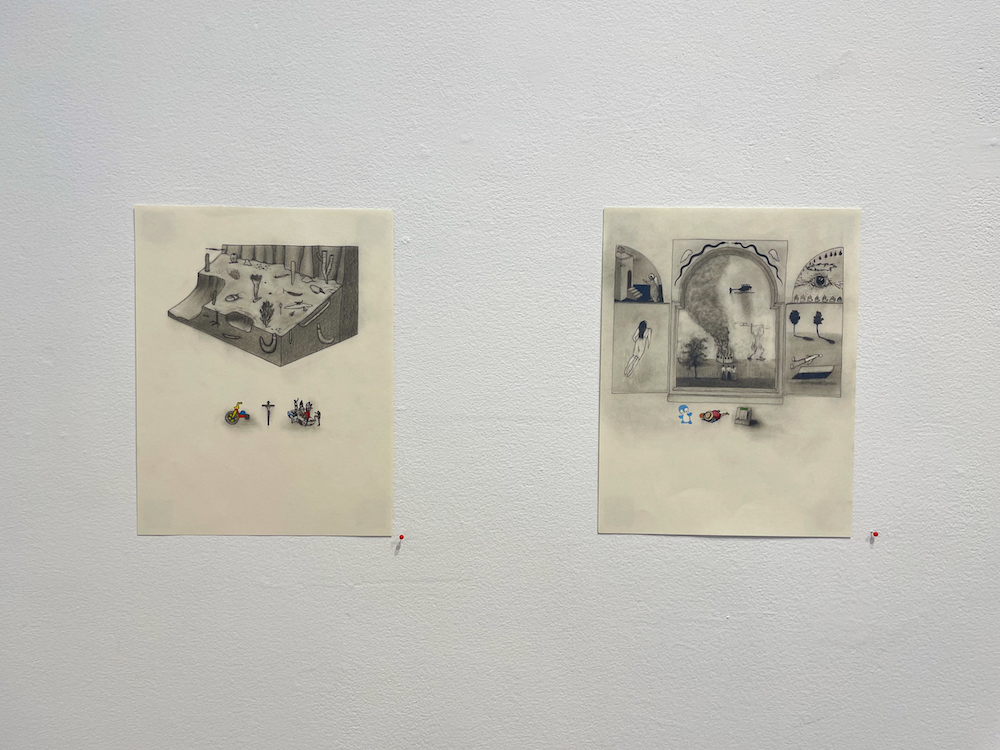

Invoking images of premonitions, destruction, and rebirth, artists Stephanie Barber, Patrick David, and Josh Dorman weave hyper-specific yet open-ended mystic narratives in Early Blossoms/Perilous Thirds at Current Space. Dorman, who hails from Baltimore, makes densely layered collages with antique paper, ink, acrylic paint, and resin; David creates charcoal and colored pencil drawings; Barber presents ceramic sculptures and fabric installations with poetic texts. Both David and Barber currently work and live in Baltimore. The show was curated by Current Space co-directors Michael Benevento and Julianne Hamilton and member Andrew Shenker.

From afar, the alluring bright colors and forms on display seem inviting, but on closer inspection I notice that characters are missing heads, the landscape doesn’t abide by the laws of physics, or there is a hint of the supernatural. Morphing between dream, nightmare, and meditation, the drawings, collages, and sculptures transport the viewer to different realms. With an armed crisis in Europe, and uncertainty in the air from rising inflation and a never-ending pandemic, having surreal, unexpected, and strange landscapes to escape into and decipher can offer a moment of respite and contemplation.