Almost anything you can say about Russia’s war in Ukraine is an understatement. It’s a war of choice and aggression, an apathetic attempt for a dictator to strangle a much smaller country, a young democracy whose recent success, politically and economically, has proven to be a threat to Russia’s autocratic rule. This war is gruesome, immoral, and cruel—both to the Ukrainian people, civilians targeted every day, and to the Russian soldiers who are dying for a cause many of them do not believe in.

The Ukraine conflict is a lesson in what happens when the ruler of any country is too powerful, with access to a nuclear arsenal, surrounded by yes-men and sycophants, and a master of a failing economy. In many ways, this war is too tragic and absurd to even comprehend in modern times, yet we are here, each day watching footage of bombed-out cities that were prosperous and peaceful just a few months ago and of the dead, maimed, and injured.

In the meantime, those who care about this conflict are faced with few options. We want to help and to support a free and democratic Ukraine, and we don’t want to provoke a nuclear war. What can we do? We can give money to vetted groups supplying medical aid, food, and arms. And we can also send our support in energy, conversations, and by continuing to pay attention to a situation that is in different ways being distorted by disinformation, propaganda, and strangulation of communication.

Baltimore is home to a large Ukrainian immigrant population and our art community is made richer by the presence of a number of Ukrainian artists. Two friends of BmoreArt and immigrants from Ukraine, photographer and educator Elena Volkova and Critical Path Method (CPM) gallery director Vlad Smolkin, have been impacted by the current war, and their regular contact with friends and family in war zones offers some solace but mostly a constant feeling of helplessness and anger.

On February 28, Smolkin sent an emotional email out to the entire CPM gallery mailing list. “I feel especially moved to express how I feel on what is happening in the country where many generations of my family have lived and died, and where people I love are currently sitting on the precipice,” he wrote. “It feels important to reiterate that this is not a civil war, or a disagreement within one country—this is one country violently invading another free and democratic country.” Smolkin’s email inspired numerous responses from his gallery patrons and colleagues, prompting him to think more about what he, an American citizen, can actually do, given this country’s guarantees of free speech, freedom to assemble, and freedom to protest.

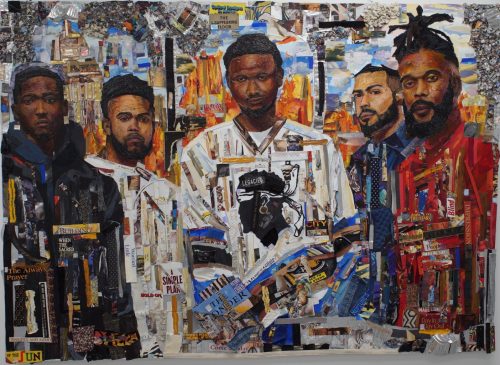

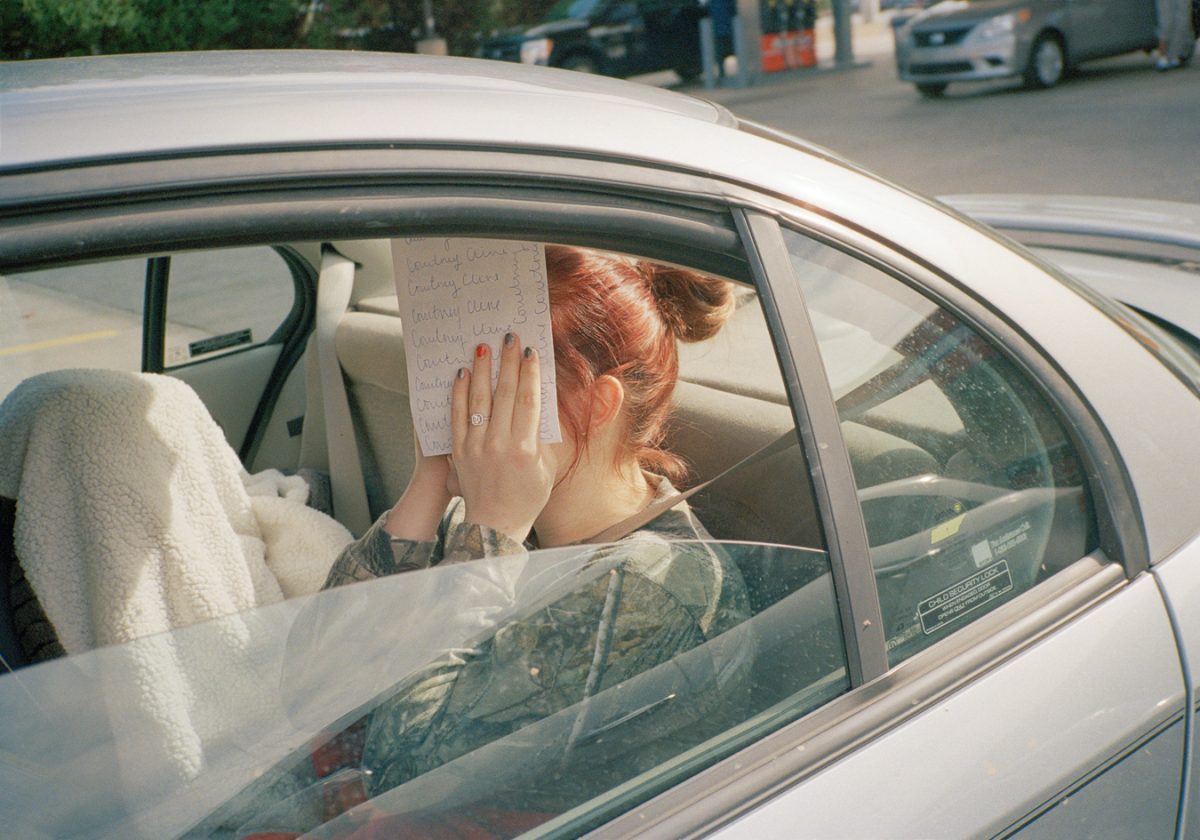

In the gallery, CPM is currently showing Traditions Highway, an exhibition of contemporary photography by Irina Rozovsky, a Russian-born artist with family ties to Ukraine. On view through April 8, the show includes 16 photographs made from 2015 to 2021 with a group of collected vernacular landscape paintings, and a text piece created by Rozovsky in 2021 while driving on Route 15, a Georgia state road known as Traditions Highway. The exhibition visualizes photography’s power in emphasizing the metaphorical qualities of everyday events. The artist’s own experience as a Russian immigrant in the USA created an opportunity for this cathartic, wide-ranging, and intimate conversation with Volkova and Smolkin.

This conversation took place via Zoom on March 9, 2022, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.