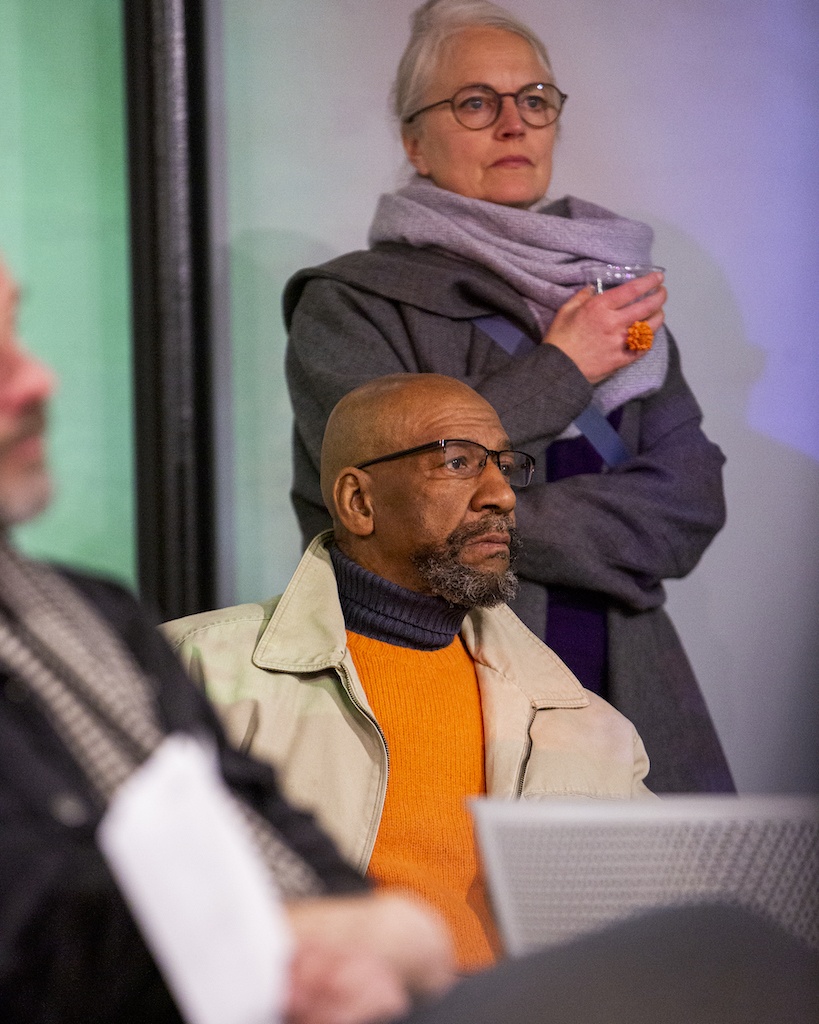

Audience Question (Jenenne Whitfield, AVAM): I just think this is important and want to ask… I think there’s a connection between discards and discarded people. That’s what I feel you’re talking about. I also think that word justice is very profound, there is a real connection to that. And is it possible that we’re working through something internal as we are rescuing these things?

Adam: I think to some of us it’s inherent. You know, Jordan and I did not know each other before this show. And most people come into this room and they can’t tell where one us stops and the other one starts. That to me says so much about where we are, what our souls’ need to work is… And for me, it’s inherent that the reclamation point is not just the recognition of the resonance and the importance, the grace and the holiness of our voice, which is found in all this detritus. But in that sense of giving weight to the voiceless, like that situational availability that is then found in the equality that our garbage gains.

Once it’s down there and in the stream, no matter if it’s bright orange or blue or yellow, it’s all the same. It’s just garbage. And to be made beautiful, it’s got to be given that high energy and nurture and life. It’s inherently connected to how we feel about healing ourselves. You have got to take the time to bend over and do it, to pick up the garbage, and to some extent, to grow up and be responsible adults.

Our culture is full of adolescents, you know, who are afraid to be responsible for it. That’s where America’s at, where society’s at, just growing up outta mom’s basement. It’s time to get a job. It’s time to be responsible, to face the music in this nature. And it’s rough. Jordan, what do you think about these questions?

Jordan: Well, when you were talking about justice and respect, I think you can’t even respect yourself if you’re throwing trash over your shoulder. You’re certainly not respecting the planet you live on. When I lived in DC, what I thought about the most was inequality. It was a violent time in DC. A lot of this work spans a long period of time… The willingness to abuse ourselves, each other, the planet, it’s all there, that lack of care. To be able to somehow resurrect what was cast off and to nurture it and give it a new life, a better life, there’s a lot there. And also just, the value of spending time in the places that people are afraid of, they’re undervalued places.

Lee: We said we wanted to break the line between audience and panel, so this is a great moment to pivot. We’d like to invite all of you, if you would like, to stand up, move around if you’re inclined toward a specific piece of art. If there’s a piece that’s speaking to you that you’d like to put forward? If you want to also have a chance, to interact a little more with pieces that you’re interested in and how some of the things we’ve been talking about are manifested in the work. So if you are so inclined, if you’d like to get up and move to something that’s really speaking to you, you want to get a little more intimate with it, and we can move around and have the artist share a little bit more about this particular piece.

Jeffrey Kent: I’ll start. So this piece right here with these bobbers right here (“LIfe Ring”), can you tell us a little bit about the collection of these beauties? I remember coming to your studio and I think this is one of the works that really resonated with me. And you don’t even see these things anymore.

Jordan: It’s fascinating how many people will entertain themselves by getting cheap fishing gear and sticking it in these streams where you would never eat the fish.

For me, this is a collection of years and years of walking around. I’ll find one and, often, the fishing line is really dangerous. I find them in parks dangling from a tree, once with a hawk still alive, with the line wrapped around it. So the fishermen who are entertaining themselves by that one weekend where they go out and they leave all their junk around are really awful. But you know, these function as a symbol as well. A lot of the things I find are almost like a language or metaphor for something that I need to speak about. I may not know when I collect it, what it is gonna talk about, but eventually, each of the things is animated and it has a voice.

This whole thing started when I read an article about a ring. It was a memorial ring from the fourteen hundreds, I think. It was a sea captain’s wife, and the ring was inscribed on the inside: “The cruel seas, remember, took him in November.” And that just got lodged in my head and so I created this thing.

Audience 2: When did the form of the heart take shape?

Jordan: I’m not exactly sure. These are not linear thoughts. I probably imagine they’re actually floating symbols in my mind, sometimes for many years.

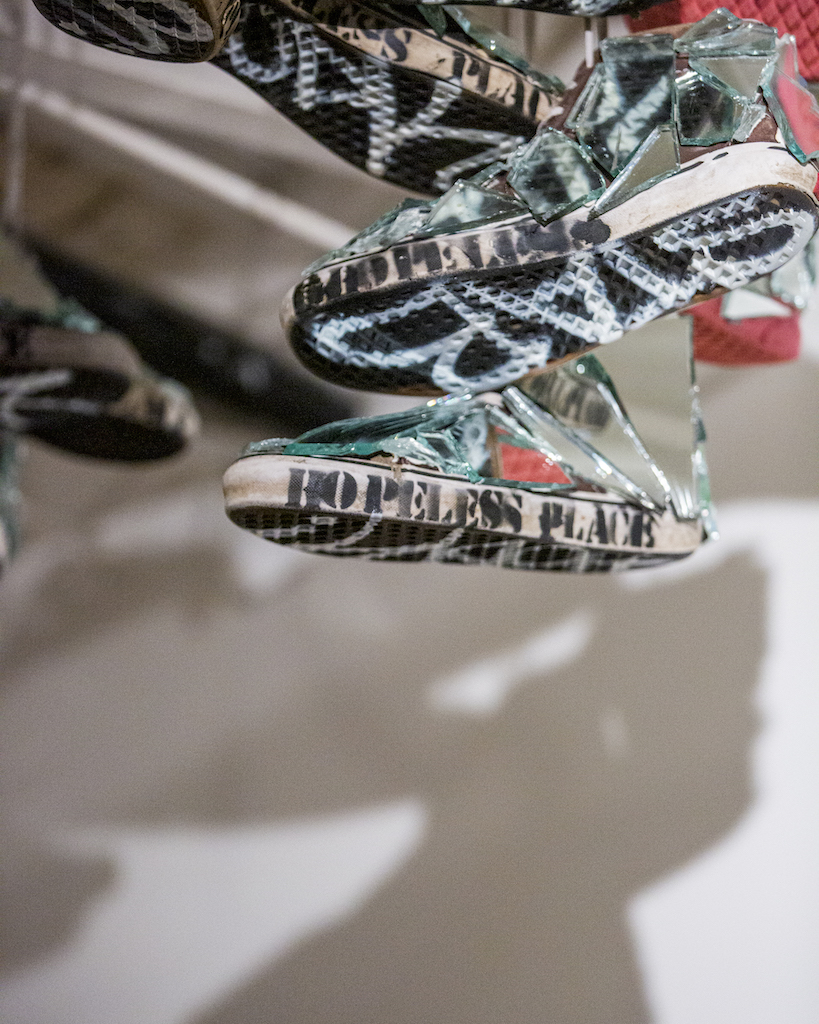

Audience 3: (Points to “Ceremonial Garment, Late 21st Century, Jones Falls Settlement, 2022). This piece really reminds me of a gladiator suit and it’s incredibly epic. And, I just want to hear more about these tool handles.

Jordan: So I like those words you used, epic and mythic. For my whole life I’ve basically survived by making and building and fixing things. I inherited my father’s tools and my grandfather’s tools and, when you have a lot of tools in your life, sometimes they break and maybe you fix ’em, maybe you don’t. And so there’s a box of tool handles in the corner, or you see some tool handles in a thrift shop and you think, I’ll need to fix tools, I’ll get those handles. And so eventually you end up with hundreds of handles and there’s something about that capability that is magnificent, but it’s also a responsibility.

At my house, if something breaks, I have to fix it and (laughter), and after a lifetime of that, it’s heavy. And so, this thing actually is quite heavy, for real. And so I imagine that cape as being a symbol of the person who has that life. I guess it is somewhat autobiographical, but I’ve also known people who are even more so like this and they’re inspiring to me. I think in our culture, they’re important figures, especially now because of our throwaway society. We don’t fix anything anymore. Everything is plastic. You can’t even fix most of it.

Audience 4 (Ed Berlin): I wanted to ask about collage. When I was first introduced to the concept, it was to combine different pieces to tell a story that in most cases was really separated from the pieces themselves. I always assumed that the pieces were just like the bricks which make up the building.

But, what I hear you saying is that there’s a duality in your collages. That you’re telling an integrated story using these found pieces as elements. But the pieces themselves speak to their own individual history. And the viewer vibrates between getting the intended story of the collection and then dwelling on the source of the components, which really opens up the whole concept of collage to a kind of a whole new, maybe for me, new meaning, maybe not for you. It’s interesting to think of it that way.

Adam: I’m definitely a collage newbie. When I got into this position, or this color-way, as a practitioner this is only my second foray into working in collage with this kind of comment. My first color way, first collage series, was much darker, with a heavy worker-based art energy included with a very urban aesthetic. I have to say that it was in that way of working with a collage medium that I realized that I am actually an okay painter… Oddly enough, these collages are the best paintings I think I’ve ever done. And they’re not even paintings, really.

What you just touched on and how you describe that to me is how good music works. One time you’re listening through the song, you’re really appreciating the lyrics and then the next thing, the melody goes through you, and it is just about the melody of the beat. And that’s how something that really bears worth on all levels is a good piece of work. I enjoy and know that I’ve gotten to a point of being able to find completion in these works when they contain an element of that available dialogue and storyline.

But at the same time, I want it to be able to be just appreciated as rhythm. I don’t want these images to have to be deep every single time. I want you to be able to appreciate the motion and the energy and movement, the background. And so they’re designed a lot like repeats for wallpaper or patterns that aren’t meant to be overly studied. But then once you realize that the study’s in there, they’re meant to be able to hold you.