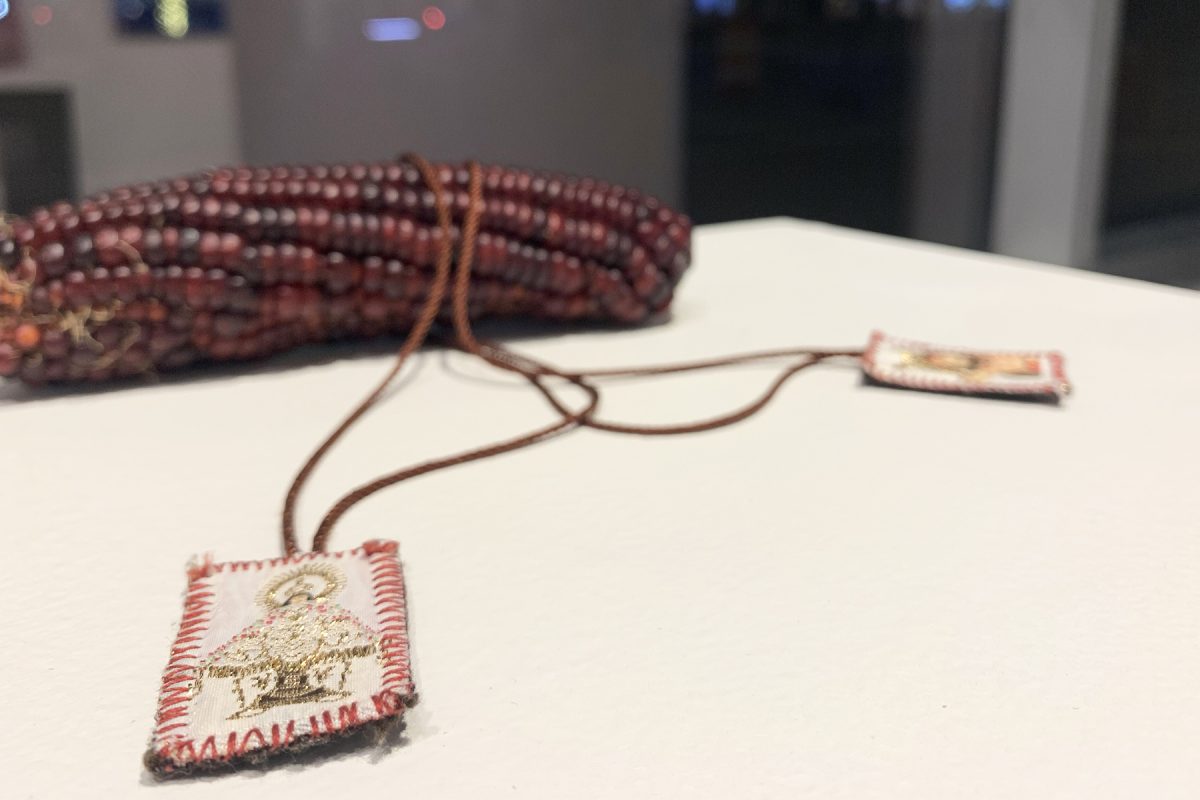

Edgar Reyes’ grandma knows that when he comes to visit her in Guadalajara, he’s going straight for that one dresser drawer that’s full of photos and messages from the past. He will pull out the drawer, place it on the kitchen table, on top of the shiny, floral tablecloth, and start with his questions.

“Who’s this? Who’s that? Why do you have this? Can I open this letter that somebody mailed to you in 1994?” Reyes recounts the dialogue. That 1994 letter held a Polaroid photo that he’d sent his grandma from Virginia, where he and his mom had just started to settle in. “I was blown away because I was, like, six years old. I don’t remember taking this picture. I could imagine my mom making me write the note on the Polaroid to send to her.”

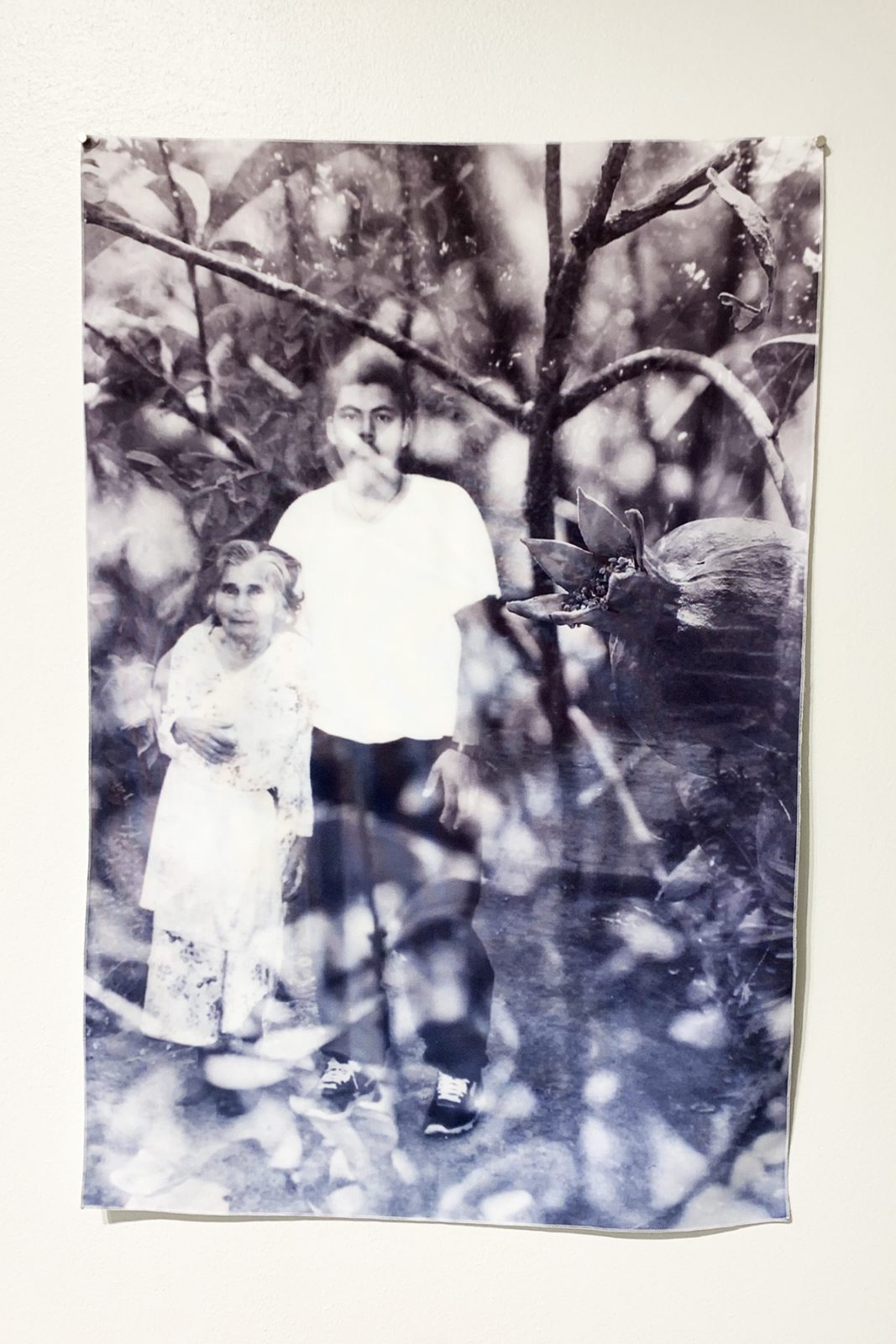

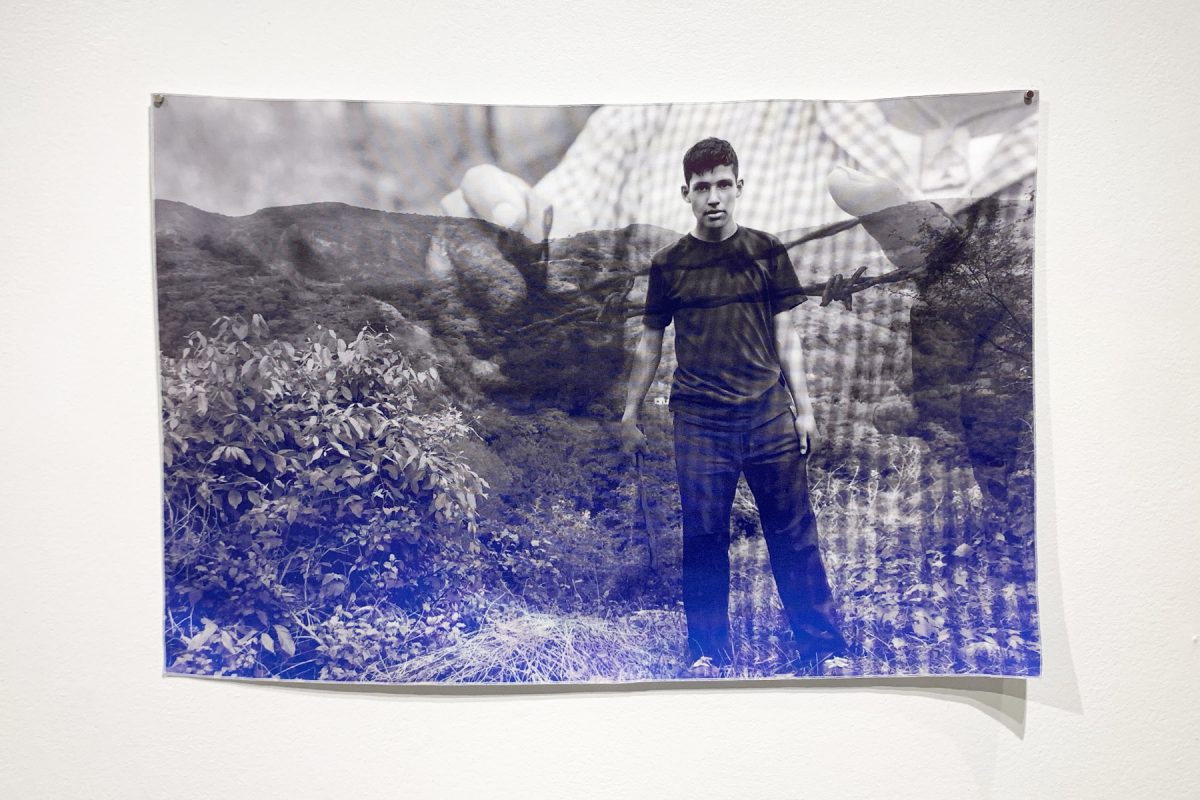

Only occasionally does Reyes’ grandmother let him actually take any of those treasured photos back with him; more often, he photographs them and uses the images in his digital collages, installations, and prints. “My grandma doesn’t like getting rid of photos,” Reyes says. “She likes me seeing them and photographing them.”

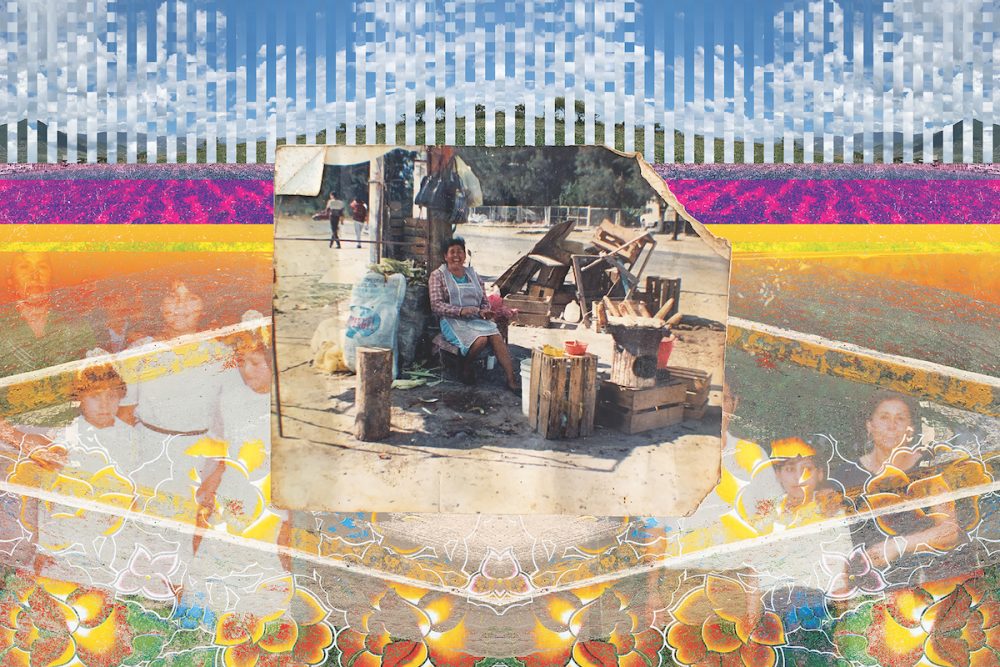

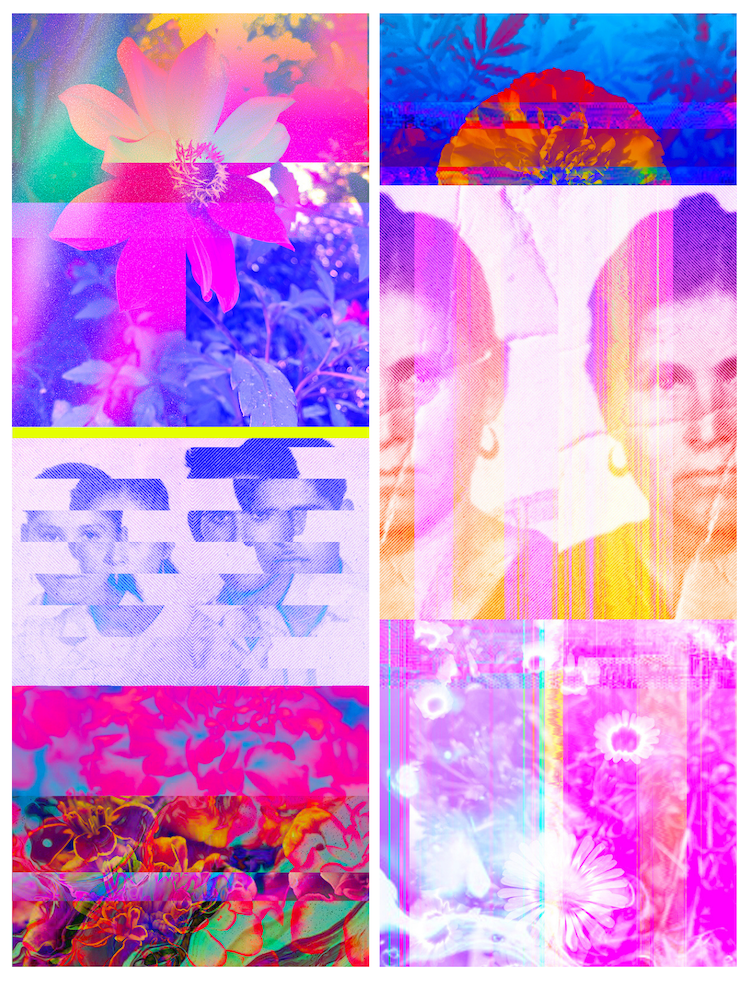

That Polaroid photo appears in a piece in Reyes’ current solo show, Fragments at VisArts in Rockville; it’s reproduced within a large collage printed on billowy chiffon. In the photo, young Reyes looks overjoyed, mouth agape, sitting close to his smiling mother. On the wall behind them, a small icon of Jesus Christ keeps watch, nestled into the photo’s upper right corner. The white border bears a handwritten caption: “Con mucho cariño para mi Abuelita” (with much love for my Grandma). The clarity of this photo anchors the rest of the piece, which is awash in dreamy, technicolor clouds and modular plants that glitch and cut out just like memory does. Installed in the gallery, the piece itself never stays stagnant, just like memory doesn’t; the room’s airflow makes the delicate chiffon undulate.