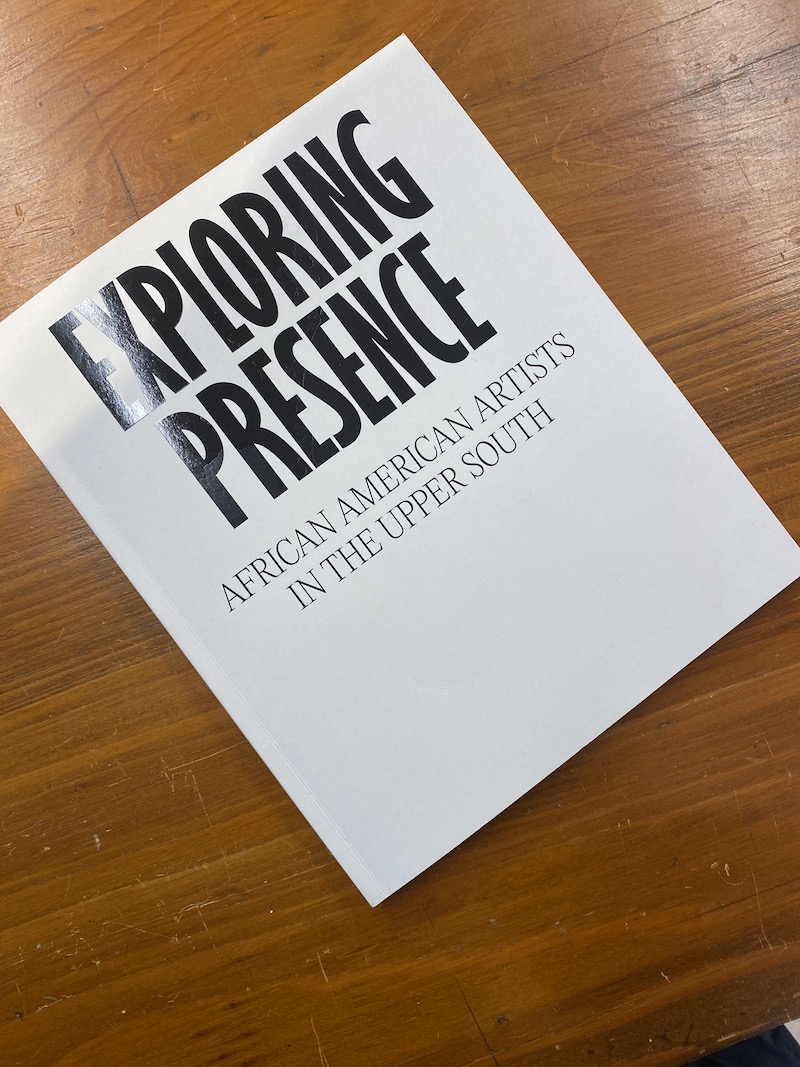

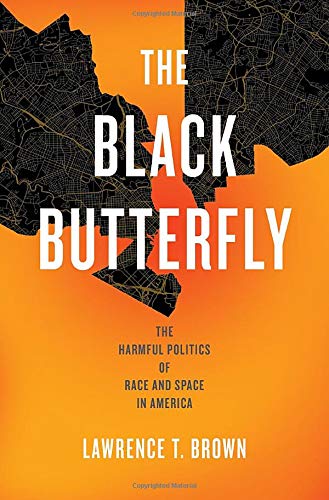

We Used to Live at Night (Culture Crush Editions) and Shuttered (Baltimore Museum of Industry exhibition catalogue) by J.M. Giordano

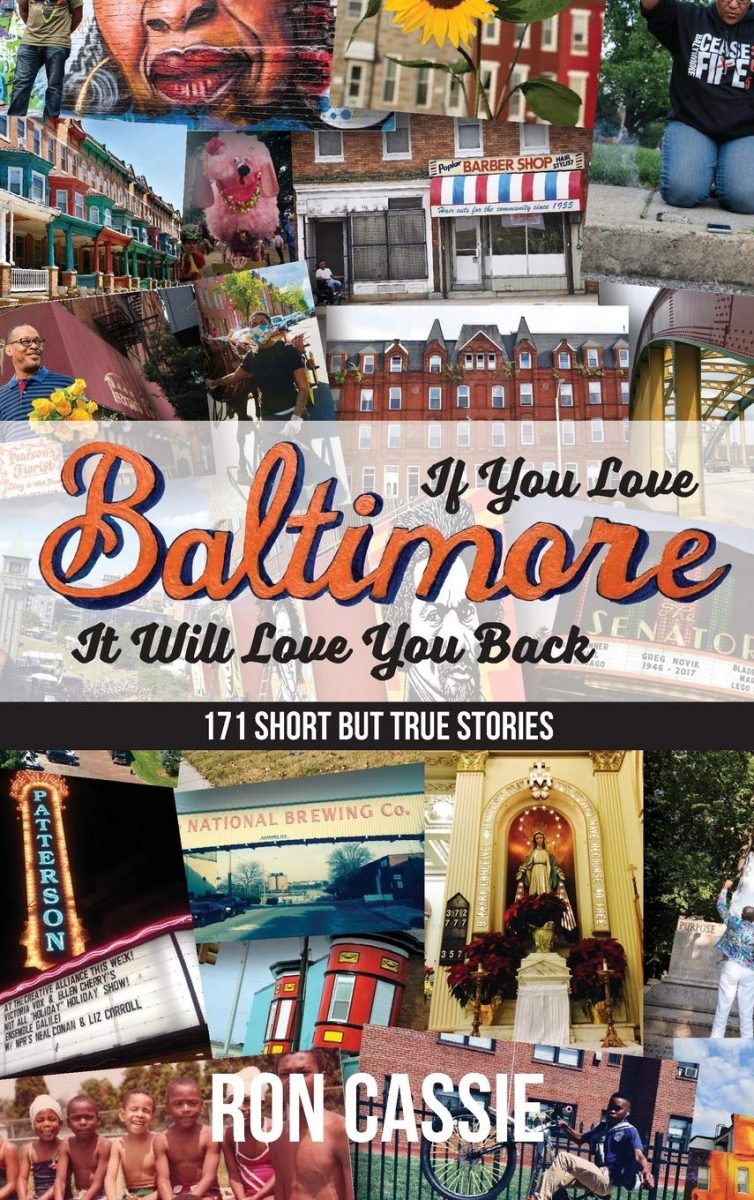

It’s hard not to get sentimental—or just, frankly, sad—at the end of the year, especially after another harrowing and traumatic year of an ongoing pandemic. Trying to make sense of anything at the moment, extracting a lesson from these experiences, seems futile and foolish. I personally would like to sit down for a bit in the gray abstraction of life right now, just a little rest. I’m pickier than usual with media and books and find more comfort and possibility lately in the visual rather than the textual. A friend of BmoreArt (and another former coworker of mine), J.M. Giordano is a great photographer of Baltimore, capturing scenes of the city as various as drag performances and protests and dive bartenders and ghostly remains of industry. We Used to Live at Night presents 25 years’ worth of photographs Giordano took around Baltimore City while he was “off-duty” from his official work as a photojournalist. “From its bars, night clubs, inaugurals, casinos, strip clubs, drag nights, hip hop battles, and the too often encountered crime scenes, this incredible work paints an intimate portrait of Baltimore culture,” reads the publishers’ description.

Another recent book of his, Shuttered, is the catalogue to his 2020 exhibition with the Baltimore Museum of Industry, documenting the steel industry’s collapse in Baltimore. Good union jobs at Bethlehem Steel in Sparrows Point brought thousands of people to Baltimore in the 20th century. The factory officially closed in 2012 after many years in decline, and now there’s an Amazon warehouse in its place. The grandchild of a steelworker, Giordano began this project in 2004, working for the Dundalk Eagle. The photos are stark and human and, like everything around us right now, they present more tense questions than answers.