Octavia Butler famously recorded her intentions as a Black woman science-fiction writer through various notes to self on paper, on the margins of drafts, and in journals. In one oft-quoted back-of-the-notebook scrawl, Butler declares that she will become a bestselling writer whose work is reviewed in big-name publications and who will use her fame to get herself a nice house and to “help poor black youngsters broaden their horizons,” among numerous other promises. “SO BE IT! SEE TO IT!” she exhorted herself. And she did.

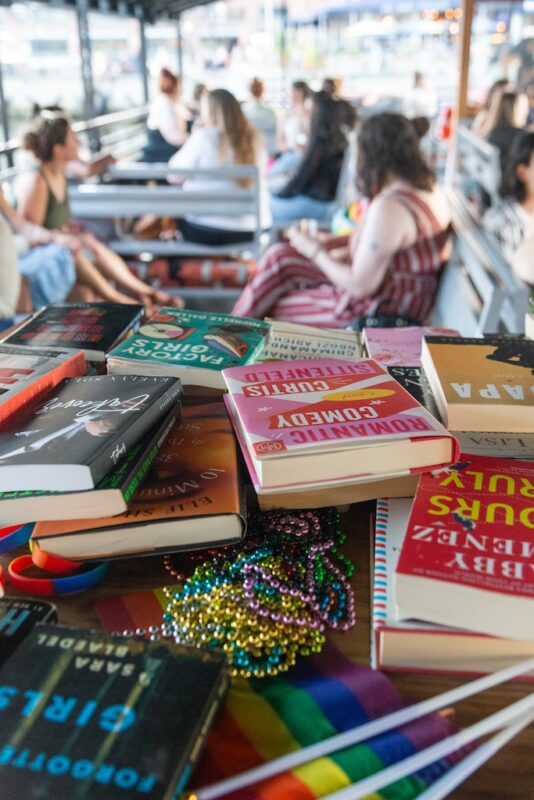

Butler’s note was one of many sources of inspiration for participants in the latest session of A Revolutionary Summer (ARS), the reading and writing program for Black girls cofounded by Andria Nacina Cole in 2015. Each summer culminates in a final public project or presentation; previous iterations included a mural of Black women writers the girls painted with Megan Lewis, a children’s book they published, and a play they wrote. Summer 2021’s final assignment was to write a manifesto.

Throughout ARS’ eight-week program, participants age 15 and up (known as Daughters) gather with Youth Leaders (currently ages 18-22) and adult leaders (aka Mamas) for reading and writing workshops, guest artists, one-on-one coaching sessions with Black women writers, political education, yoga, and mindfulness, among other activities.

All of these activities, especially these interactions with literature, visual art, and film in community with Black girls and women are meant to encourage the daughters’ ability to tap into their own internal authentic power, as Cole described it to Jalynn Harris in a BmoreArt profile. “Where external power comes from resources Black women have historically been locked out of—money, land, influence—authentic power is something you always possess,” Harris wrote. “It’s the ability to manage yourself, remain in your integrity, uphold your boundaries, and, as much as possible, take the higher road.”

The 2021 summer session was held in person during that sweet chunk of time post-vaccine when we all thought the pandemic was just about over. Daughters studied texts such as Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X, Sister Souljah’s The Coldest Winter Ever, and Audre Lorde’s The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, music including Jazmine Sullivan’s album Heaux Tales and SZA’s Ctrl, and paintings by Megan Lewis, among other works of media and culture.