There are numerous notes and observations from this year—from March, onward—in my Google docs, half-baked pieces of writing about online “art viewing,” anxiety, distraction, collectivity, upheaval, and productivity that I probably won’t finish. Portions of them feel worth sharing, while others are entirely useless for anyone else to see, and either way, throughout the year I’ve told myself there’s more important work to do and I close the tab. Much of this writing is ostensibly about nothing, or otherwise it is a container for things I noticed and wanted to remember from within my environment—my house, which I hardly ever left.

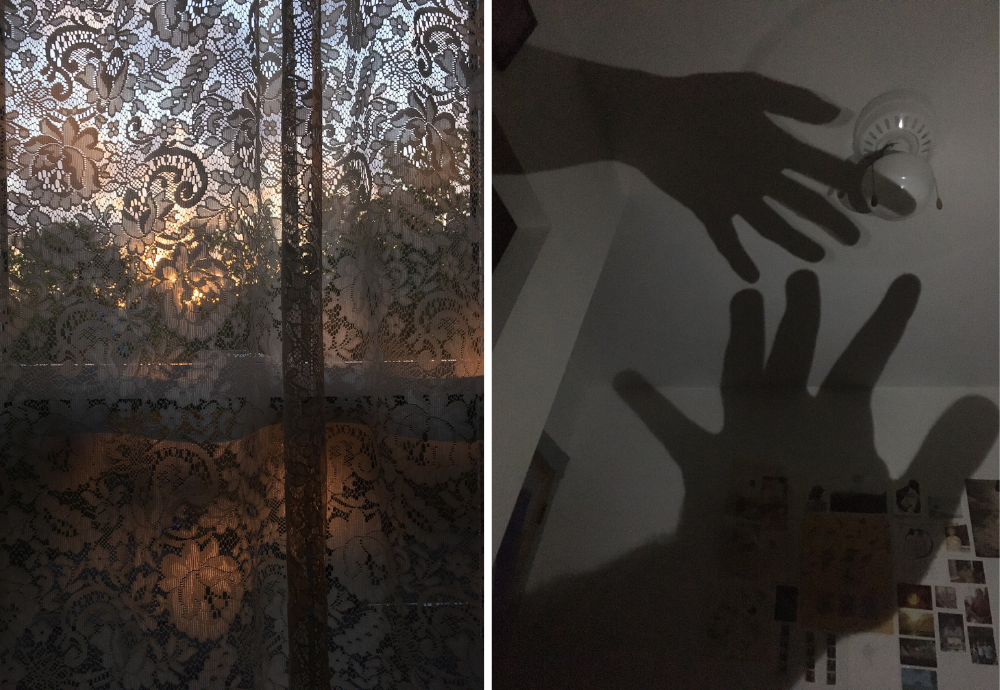

Here’s one snippet of the latter, from early April: Every day the backyard tree, Bradford pear, has gotten greener. I wake up to this tree out my window. For months it was winter-bare and harsh, then spring came through and it budded, flowered. The blossoms were white, the petals tiny and delicate as a baby’s fingernail, and they bobbed around, crowding my window. Slowly, and I missed it somehow, the light green leaves came out, and I imagined feeling the new growth, a rougher satin or maybe a smoother suede. I don’t have a good reason for not going out to touch the new leaves but I think it has something to do with what I’ve lately been calling the necessary precautions. […] Circling back to the feeling of ineptitude. / Trying to make a tree be more than a tree.

I’m not sure if I was really trying to make a tree be more than a tree or if I just wanted to appreciate my ability to watch it grow. The easy ritual of just looking and taking notes in a rare, quiet moment in what was to become an absurdly worse year.

It feels important to write some cogent, thoughtful summary about the year, but it’s impossible. Looking back and assessing the past twelve months is harder now than in previous years because 2020’s devastation is still raw and infuriating, and it is not over. But okay, I’ll bite. What have we realized, or re-realized, or realized for the nth time in 2020?

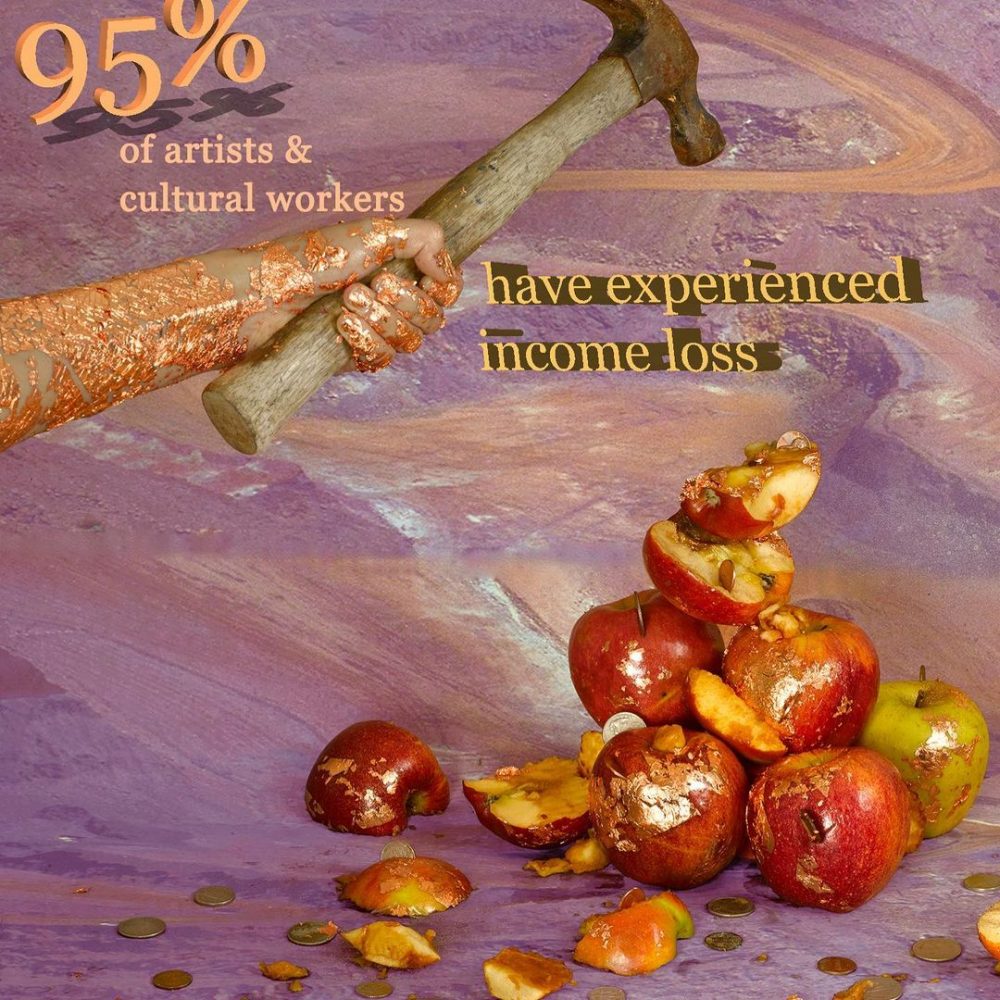

Here are some things: Our structures are untenable. Nothing is certain. Wealth and cruelty are inextricable. Most people’s precariousness is invisible to those who’ve never experienced it. Individualism is a sickness, illness is political, and time is fake, among other Holzer-like truisms I’ll regret writing later.

Throughout the year, I have circled back to what we in this country understood about the pandemic in March, when terms like “social distancing” and “flatten the curve” were new to most of us and when we didn’t even know if wearing masks was effective. I remember the early rhetoric that said if we didn’t all “stay at home,” around 80,000 Americans could die and many more would take ill. When places began shutting down, many of us had no idea that by December we would still be here—with scarce support from the government that would be funny if it wasn’t despicable—and with more than 300,000 people in the US dead from COVID-19, and counting.