I read an article the other day about the ultimate Covid-19 art pivot that gave me hope but also made me throw up in my mouth a little.

The story featured a young musician who had just finished a master’s degree in cello performance. She had a full-time job lined up with an orchestra but it all disappeared with Covid-19 closures. Like many others, she went on unemployment, but (silver lining alert!) started teaching music lessons virtually to a few students to make extra money. She didn’t realize that there were so many kids and adults stuck at home wanting to learn an instrument in their spare time; her teaching schedule quickly filled up and now she is making more money than she would have in the orchestra.

I know that the reader is supposed to view the cellist’s pivot as a miraculous success and to feel #grateful to see an artist earning a decent income during a pandemic, but I don’t see it that way. While I’m glad the cellist is not starving or unhoused, the world is being deprived of her contribution to our cultural heritage, and this matters. Her goal to earn a living through professional performance may have disappeared or been indefinitely postponed for years to come, if we even have live orchestra performances in the future. Not only is the cellist missing the foundational years of her career, in terms of building skills and professional networks—spoiler alert—she is going to be knocked off her ass by self-employment taxes this spring.

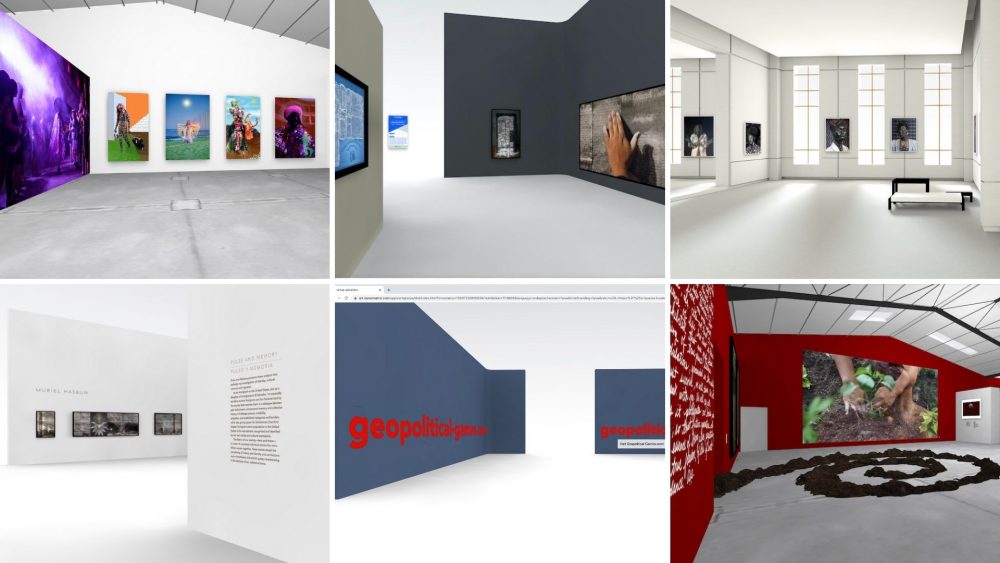

Right now, all of us who work in a creative field have been forced to reconcile our long-term vision with short-term issues of survival. Our temporarily closed world, bereft of daily distractions and errands and drinks at the bar, is laid out in grim detail: the lack of any sort of reasonable economic protections, government resources, or a safety net for life-or-death health decisions is so much clearer now. For artists, this was all true before but was easier to ignore because we were all busy with a sense of forward momentum. Now, artists and culture workers are caught in the crosshairs of a health and economic breakdown that renders our professional creative goals irrelevant while our skills are still valuable, just not for their intended purpose. All previous rules and measures of success are now invalid, and there is always room for an art hack or pivot, but online “viewing rooms” instead of exhibitions and fairs and concerts can only go so far.

I don’t know what the best course of action is for an artist during a global pandemic, but I am wondering if survival and relative mental stability are the highest goals we can attain right now. As our world continues to shrink down to bare essentials, I keep searching for a silver lining or gem of wisdom after a year of uncomfortable compression. Although there is a cliché about artists making their most significant discoveries during troubled times, I’m not sure it’s possible to do one’s best creative work in an environment of fear, poverty, loss, and death.

During dark times, art and a continued insistence upon making it provide essential spiritual nourishment that our society needs, whether people realize it or not. Given how difficult it is for so many individuals to pay their bills and put food on the table, making art at all seems like a mirage of a world that no longer exists. Should we attempt to become like the cellist in the cheerful pivot article and use whatever skills we have acquired for practical purposes and embrace a new economic model, or is this type of compromise a trap that we should avoid at all costs?